Andrew Morley FRSA argues that those advocating restricting the wearing of the veil in court should tread carefully and consider the evidence around the importance of fairness in our criminal justice service.

The Lord Chief Justice recently announced that he intended to launch a consultation on whether veils can be worn in court. This followed an intervention by Ken Clarke, the former Justice Secretary and Lord Chancellor, who was reported as saying that the wearing of the veil 'undermines justice'. The sequence and level at which these interventions come may lead some to conclude that restrictions on the wearing of the veil in court are imminent making it even more important that there is some reflection before we rush to judgement on this issue.

There will be those who reject Ken Clarke's view on the basis that traditional values of fairness and tolerance will prevail; a position well articulated by Damion Green the current criminal justice minister who, when asked for his view on banning the wearing of the veil in public, said he thought it very 'unbritish' to tell people what they could and could not wear.

Of course, there are circumstances when it will be necessary for the veil to be lifted, for example, when it is necessary to confirm identity. Immigration officials and the police who routinely deploy female members of staff to avoid causing offence to religious beliefs already sensitively and competently handle this on a daily basis.However the reasons put forward for the removal of the veil do not really stand up. In this case, the primary argument seems to be that judges and juries need to be able to see the witnesses face during a trial in order to assess the genuineness of testimony being given. Avid listeners of Radio 4 would, no doubt argue that they are perfectly able to discern openness and genuineness in those being interviewed on the Today programme but it also ignores other factors that can influence how testimony is perceived For example nerves on the part of the witness or prejudice on the part of the juror. Whilst witness credibility is a consideration the Judge has a key role in ensuring that deliberations are informed by the facts of the case, encouraging a distinction between what witnesses say and how they say it. But even if wearing the veil in court does impact the way in which judges and juries perceive the witness, surely it should be up to them to decide what impact the wearing of the veil might have on how their testimony is judged. Any competent prosecution or defence advocate would advise any witness on the limitations, if any, of giving evidence whilst wearing the veil and how that might impact on any findings. In advancing the case for any change in the rules around this issue the consequences should also be considered.

What is certainly true is that any restriction on the wearing of the veil in court would add to a growing sense of alienation amongst many in the Muslim community and risk the justice system being perceived by some as being unfair. This has implications. Tom Tyler from Yale University has developed a body of research that shows that the perception of fairness of the justice system and by extension, fair and respectful treatment, is a significant factor in securing compliance with the law. This is more significant than any perception of effectiveness. This has been reinforced by LSE research that suggests the significance of interactions in securing trust.

So what would happen if significant numbers of women refuse to comply with changed rules? Would we see judges instructing court security officials to forcibly remove veils? Would we see women being found to be in contempt of court and subject to the ultimate sanction of imprisonment? How many prisoners of conscience would it take before any rule was reversed, and at what cost to community cohesion?

Rushing to put in place rules that required the removal of the veil in court is a mistake. As well as there being questions of practicality, it runs the risk of alienating a whole community from our justice system. The justice system is predicated on cooperation and confidence, and compliance with the law on fair treatment. We undermine these at our cost.

Andrew Morley was the chief executive of the London Criminal Justice Partnership from 2005 – 2011. He now advises on issues related to safety, security and justice and is a senior visiting fellow at the Institute of Criminal Policy Research, Birkbeck College, University of London.

Related articles

-

Worlds apart

Frank Gaffikin

We are at an inflexion point as a species with an increasing need for collaborative responses to the global crises we face.

-

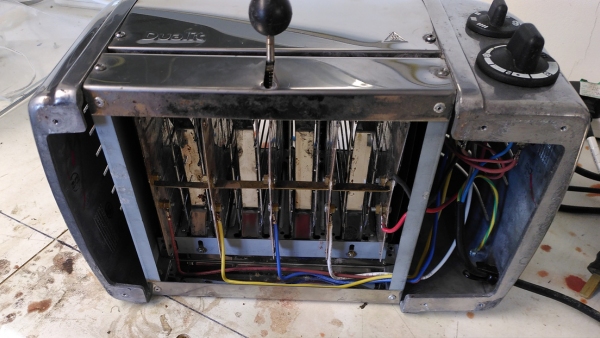

Why aren't consumer durables durable?

Moray MacPhail

A tale of two toasters demonstrates the trade-offs that need to be considered when we're thinking about the long-term costs of how and what we consume.

-

You talked, we listened

Mike Thatcher

The RSA responds to feedback on the Journal from over 2,000 Fellows who completed a recent reader survey.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

I strongly agree with what Andrew Morley is arguing in "The

face of justice?" Only absolutely essential requirements should be made

legally-binding otherwise it brings the law into disrepute. And that is the

opposite of encouraging social cohesiveness in society in which all

members feel respected and trusted by others. Especially in societies claiming to be democratic, encouraging trust is of supreme importance.