The pace of change in the labour market has accelerated tremendously. Juan Guerra FRSA argues that we need to be constantly learning to perform to our fullest potential and outlines some proposals that would allow millions to utilize and develop their skills.

For the UK labour market to thrive, for people to realise their potential and better their standards of living, there must be mechanisms that smooth the upskilling and re-skilling processes so that workers progress. We need to be flexible and adapt to new circumstances: change jobs, change geographies, change industries, develop soft and hard skills, and deal with partners from around the world. Today, however, there is great friction in the system. 43 percent of workers, or some 13 million people in the UK, have skills they are not using at work; the third highest proportion of all OECD nations.

Employers face upfront costs by having staff spend time on training and education. Employees face upfront costs when they need to pay for courses or simply because they may need to stop earning to spend time in education and training. Government has an interest in supporting training and education but cannot bear the entirety of the cost.

Employers, employees and government all have a stake in the matter. What platforms can help them work better together to achieve a common goal? The RSA City Growth Commission report, Human Capitals: Driving UK Metro Growth through Workforce Investment, outlines some recommendations for how government can make smarter investments at the ‘metro’ scale; guided by city-regions, which cover the labour market geography of commuting and job search.

But, there is a case for further financial innovation. A few months ago I was visiting a university in London where, as it turns out, many engineers from Kent traditionally upgrade their skills. Lately, however, Kentish engineering firms have been struggling to partially sponsor courses for their staff, as well as having to them spend hours in training and not on the job. The university has stepped in to provide some scholarships, but that is still not enough. The engineers themselves would be more productive and able to earn more in the future, but cannot afford their courses today. Firms, their staff and the university all have a stake, but lack the means to collaborate efficiently.

If the engineer seeking to upskill had access to a postgraduate or professional loan, he or she could pay for the course over time, the firm would benefit from his or her skills and the university would inflow additional tuition revenue. Surely, the Government should have an interest in backing this type of loan scheme. This is the purpose of the Professional and Career Development Loan, which, unfortunately, is now only offered by two banks to a small number of people these days.

Although government involvement would be helpful, it is not required. In fact, a loan scheme may not even require cash. Sometimes all it takes is spare capacity. Universities could simply agree to receive tuition payments over time for seats that would have otherwise remained empty. If the course provider lacks the ability to manage this ‘loan book’ in house, external partners can do it and ensure a high level of repayment. The fact that borrowers are already employed would make this a relatively low-risk proposition.

This model is a collaborative economy model, where an asset – in this instance, spare course capacity – is being put to work through the provision of credit. Another asset, human capital, is being enhanced.

Another model, which is often overlooked, is peer-to-peer learning. As the Human Capitals report identifies, the existing workforce is the prime driver of future economic growth.

In a previous life I worked in a human resources department of a plc. People used to talk about the 70/20/10 model, where 10 percent of the learning came from the classroom, 20 percent from peers and 70 percent on the job. Companies can easily encourage staff to support each other’s professional development. This builds skills, trust and resilience in business without costing very much, if anything at all.

Senior staff have much to learn from junior staff and vice versa. So, if 90 percent of the learning can be generated within the workplace and cost so little, why not start there? It is clear that those who manage organisations have a huge responsibility in realising the economic growth potential of 30 million UK workers. We need a range of approaches to fully unlock the power of human capital, in our major cities and beyond.

Juan Guerra, FRSA is passionate about social mobility, education and meritocracy. He is the founder of StudentFunder.com and has a background in micro- and SME finance. Juan holds an MBA from Cranfield School of Management.

Related articles

-

Worlds apart

Frank Gaffikin

We are at an inflexion point as a species with an increasing need for collaborative responses to the global crises we face.

-

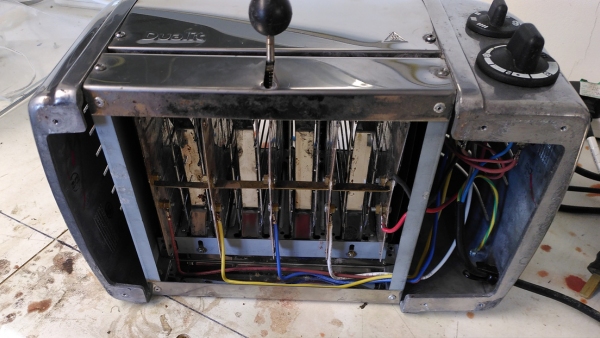

Why aren't consumer durables durable?

Moray MacPhail

A tale of two toasters demonstrates the trade-offs that need to be considered when we're thinking about the long-term costs of how and what we consume.

-

You talked, we listened

Mike Thatcher

The RSA responds to feedback on the Journal from over 2,000 Fellows who completed a recent reader survey.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.