Businesses increasingly need more than a legal licence for their activities to be seen as legitimate in the eyes of society, argues John Morrison. This additional requirement is hard to define, but is composed of a number of elements including legitimacy in the eyes of society, trust and consent for the activity in question.

The concept of a ‘social licence’ is increasingly engaging business. The aim is not a legal written document but something less tangible but very important nevertheless. A social licence cannot be self-awarded, nor is it permanent, but can provide a good way of underpinning whether businesses understand their complex relationship with society as a whole. This can be best understood as a modern manifestation of social contract thinking started over 300 years ago by the likes of Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau.

The current debate surrounding fracking in the UK is one contemporary example of the social licence phenomenon poorly managed. Whatever the case might be for shale gas or coal-bed methane in the UK (and there is a case to be debated), it has been badly made, poorly understood and consequently the new industry has started on the back foot in societal terms. This has echoes of the lost case for genetically modified crops in Europe a generation ago, or nuclear power in Germany. For business, the absence of local acceptance can be a very costly thing. A recent global survey of the mining industry suggests that the loss of the social license to operate for a mining company can be worth up to $20 million a week if production is impeded. The intangible is becoming an increasingly real business concern.

But what about politicians and governments? Do they also need social licence? The classic social contract response is a firm ‘no’; that democracy itself has answered the challenges of political legitimacy first laid out by social contract thinkers, and then by activists such as Thomas Paine within the context of the French revolution and American War of Independence. The counter-argument is that globalisation, and shifts of geo-politics over the past 30 years, have created a reality in which democracy (as traditionally conceived), whilst still essential for political legitimacy in social contract terms, is not sufficient on its own.

Let’s take the example of the recent Scottish referendum on independence or the (unofficial) referendum about to take place in Catalonia. In one of the finest pieces of political writing for a long while, Gordon Brown eloquently made the case for the United Kingdom (and the European Union while he was at it) but understood that strong civil engagement was a necessary response to negative impacts of globalisation. During the last days of the referendum campaign, Alex Salmond goaded all three (English) leaders of the main political parties to come to Scotland (and even offered them the bus fare) under the (most likely accurate) perception that they had become a liability for their own cause. The main party leaders had political licence to campaign in Scotland, of course they did, but they had lost the social licence to do so effectively.

UKIP’s Nigel Farrage has shown that simplistic popularism can mobilise politically marginalised voters in Kent and Essex, in the way that extremists are successfully achieving across Europe. The European political establishment is clearly struggling to engage with populations at a time of rapid social and economic change and as a result some have stopped listening to the evidence in favour of something else. Evidence that immigration is good for the UK economy, for example, is countered not by economic arguments, but by cultural ones: that there is more at stake than money and jobs; and that it is English/British identity (tick as applicable) itself that is somehow threatened. If it is true that nationalists and extremists are winning ground by making arguments about intangibles, then counter-arguments based only on tangibles will not succeed. Mainstream politicians need now to think of additional forms of legitimacy, as it seems that just winning elections is no longer enough. They need to reconnect with the process of negotiating the social contract upon which their own power relies.

Governments in democracies are themselves the creation of the social contract that binds society and are meant to serve the will of the people. But politicians do not seem to see any political pay off from discussions about societal or environmental risk, particularly when the benefits are long-term and beyond the next election cycle. But it can be done. Contrast recent debates about energy security in the UK with much better public engagement on issues such as smoking or HIV/AIDS, even if a shift in attitude took time. When needed, governments can shift societal norms of behaviour and attitude and reinforce their own societal licence as a consequence by re-engaging directly with rights-holders (the public) on key issues of national importance.

This might mean a future where political leaders need to consult much more regularly with the population as a whole on issues of national interest, and to do so across party lines. This evokes something of the idea of Rousseau’s Republic, modelled on the Geneva of the 18th century. Perhaps it is no coincidence that the Swiss system of referenda, like that of California or Arizona, is one of the contemporary examples of more direct and ongoing democracy. This does not always lead to more progressive politics, as the Californian ban on gay-marriages or the Swiss banning of minarets shows. But wildcard votes (whether too progressive or reactionary) can be corrected through constitutional rulings, or that of the European Court of Human Rights, despite its many detractors in the UK.

Despite the roller coaster nature of ongoing participation, there seems to be a deep desire within the citizenry of many countries for a political system that is more than “an elected dictatorship”, as Lord Hailsham put it. So business leaders and politicians have something in common: they both need social licence even if their respective roles in social contract terms are different. Likewise, non-governmental-organisations (NGOs) should not and do not escape questions of legitimacy, particularly as their traditional supporter base ages and remain predominately ‘globally northern’ in terms of their support whilst ‘globally south’ in terms of their work. Indeed, arguably, NGOs need social licence even more than governments or businesses as they are meant to strengthen civil society itself; they are nothing if they are not part of the social contract.

There are a number of policy areas in which all three sectors (public, private and voluntary) need to think much more deeply about what trust, legitimacy and consent means for communities. For example, the US think tank The Brookings Institute has estimated that at least $1 trillion of additional investment will be needed if new global sustainability goals, to be agreed at the UN next year, are ever to be met. Such investment requires deeper public buy-in. Likewise, public-private partnerships, whether to support the NHS or eradicate extreme poverty, can only ever be legitimate in societal terms if we find new ways of keeping communities engaged.

Fundamentally social license can best be managed by bringing government, business and civil society around the table to agree standards for governance, accountability and concrete actions to reduce societal risks and maximise benefits. Such ‘multi-stakeholder initiatives’ are still relatively rare, but the British Government’s belated joining of the Extractive Industries Transparencies Initiative (EITI) as well as their chairing of the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights are steps in the right direction.

John Morrison is Executive Director of the Institute for Human Rights and Business and author of The Social License: How to Keep Your Organization Legitimate (Palgrave MacMillan, September 2014). This blog is written in John’s personal capacity.

Related articles

-

Worlds apart

Frank Gaffikin

We are at an inflexion point as a species with an increasing need for collaborative responses to the global crises we face.

-

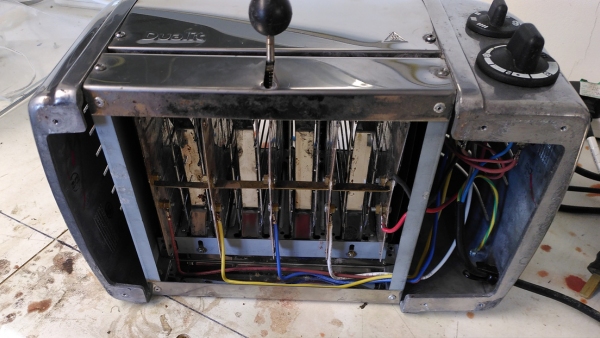

Why aren't consumer durables durable?

Moray MacPhail

A tale of two toasters demonstrates the trade-offs that need to be considered when we're thinking about the long-term costs of how and what we consume.

-

You talked, we listened

Mike Thatcher

The RSA responds to feedback on the Journal from over 2,000 Fellows who completed a recent reader survey.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

What an interesting piece which really made me think further about the legitimacy of political activities.