Local leaders across the world are changing our understanding of how to develop and implement effective public policy, says Robin Hambleton FRSA.

The recent interim report from the RSA Inclusive Growth Commission is to be welcomed, not least because it gives the idea of strengthening place-based leadership in the UK a significant boost.

The context for this study is that current approaches to economic growth are on the wrong track. It is now widely recognised that a commitment to ‘trickle down economics’, involving the spurious claim that a rising national economic tide lifts all the boats, is misguided. The evidence shows that current policies are, in fact, widening wealth, health, social and geographical divisions in British society.

The Commission’s starting point is that if you want to bring economic and social objectives together in practice, it can only happen locally. It follows that bringing about a significant devolution of power to local areas across the country is essential.

In my work on how to create inclusive cities, I discovered 17 examples of inspirational civic leadership drawn from cities across the world. A key feature of these innovation stories is that many place-based leaders have been successful in developing and implementing strategies that are guided by locally determined social and economic priorities. Based on this research I offer two suggestions on how to improve devolution policy in England and elsewhere.

Seeing like a state or a city?

First, and in line with the argument put forward by Matthew Taylor in his annual RSA lecture in September, we need to bring a much more critical eye to current approaches to public policy making. The analysis presented by James C. Scott in his 1998 book, Seeing Like a State, is particularly insightful. Scott shows how national governments, with their functional, single-purpose departments, have some of the qualities of sensory-deprivation tanks. While they may be animated by a desire to improve the human condition, ministers and civil servants simply cannot visualise what needs to be done because their ways of seeing the world are inevitably distorted. Scott argues that the very way that briefing systems, information, knowledge and power are structured undermines central government effectiveness.

Warren Magnusson, a Canadian political theorist, builds on Scott’s analysis. His 2011 book, Politics of Urbanism: Seeing Like a City, shows that the problems run deeper than the well-known patterns of silo-thinking associated with departmental government structures. He reveals how, over the years, the social sciences have undervalued interdisciplinary studies. A consequence of this is that many fine scholars, because they are devoted to particular disciplines, can also come to ‘see like a state’. An inadvertent consequence is that much knowledge creation in universities and elsewhere is fractured. His radical argument is that to ‘see like a city’ holds out many benefits and, in particular, it involves positioning ourselves as inhabitants, not governors.

Successive Prime Ministers, and their ministerial colleagues, do, of course, mouth their enthusiasm for listening to citizen voices, strengthening local economies and bolstering local democratic processes. But they do not practice what they preach.

The recent trajectory of devolution policy in England illustrates this double think. Ministers, on the basis of their own unpublished preferences, are, right now, deciding which localities are to benefit from secretive ‘devolution deals’. The process involves a super-centralisation of government power. Ministers decide the criteria, the contents of each ‘deal’, what funding will flow to the selected areas, and even insist on a particular form of governance for city regions. Directly elected mayors are being imposed on localities that do not want them.

This is an evidence-free approach and my recent international research for the Local Government Association (LGA) provides solid evidence showing that non-mayoral models of city region governance perform just as well as mayoral models.

Expanding the power of place-based leadership

Second, we should work to develop a more sophisticated understanding of the nature of effective place-based leadership. Alongside advocating a rebalancing of local/central power the RSA is surely right to suggest that local leadership capacity needs to be developed. The strategic role of local government can be strengthened, and it is clear that elected local councillors can play a key leadership role in working with civil society organisations, individuals, communities and businesses, so that all can play their part in achieving inclusive growth.

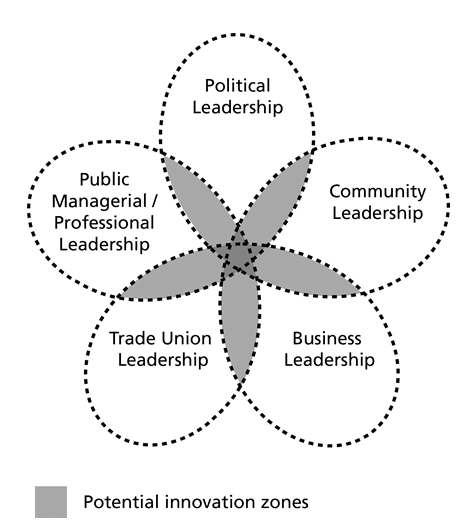

What conceptual frameworks are available to help us imagine the new kinds of civic leadership that are needed? I have found the notion of realms of place-based leadership to be helpful in developing new ways of collaborating at the local level. The conceptual framework set out belowrecognises that different kinds of people, with different backgrounds, roles and experiences, can all play a decisive role in effective place-based leadership.

The diagram does, of course, simplify the complexity of local political dynamics, but it can provide a way of visualising and organising local civic drive. In particular, it shows that all the realms connect with all the other realms and it highlights the role of local leaders in stimulating and facilitating public service innovation. It suggests that in any given locality there are likely to be five realms of place-based leadership reflecting different sources of legitimacy.

First, political leadership, referring to the work of those people elected to leadership positions by the citizenry.Second, public managerial/professional leadership,referring to the work of public servants, appointed by local authorities, governments and third sector organisations to plan and manage public services, and promote community wellbeing. Third, community leadership, referring to the many civic-minded people, voluntary organisations and other local agencies who give their time and energy to local leadership activities in a wide variety of ways. Fourth, business leadership, referring to the contribution made by local business leaders and social entrepreneurs, who have a clear stake in the long-term prosperity of the locality. And finally, trade union leadership, referring to the efforts of trade union leaders striving to improve the pay and working conditions of employees.

The realms of place-based leadership

My research shows that civic leadership is critical in ensuring that the innovation zones – the areas of overlap between the realms of leadership – are welcoming to progressive change. Leadership is necessary to orchestrate creative behaviour in these zones: behaviour that promotes a culture of listening that can, in turn, lead to innovation. Civic leaders are, of course, not just ‘those at the top’. All kinds of people can exercise civic leadership and they may be inside or outside the state. The framework can, perhaps, help local leaders comprehend and map their local power structure and explore new possibilities.

Robin Hambleton, is emeritus professor of city leadership, University of the West of England, Bristol and Director of Urban Answers. His latest book is Leading the Inclusive City published by Policy Press.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

Many thanks, Robin. This is spot on and relevant to the work we are doing in Socitm (www.socitm.net) to develop a Place-based leadership and development programme. Would bw delighted to discuss further.

As always, Professor Hambleton writes elegantly and intelligently about the key challenges we face in building a better future: one which serves the 'triple bottom line' of environment, economy and society. As always too, he offers important pointers to the practical implications of these ideas at the level of the city...or indeed any place which gives people local identity and shared interests. If anything however, he underplays the urgency of both radical devolution and nurturing new civic leaderhship to address these challenges.

As Otto Sharmer writes so persuasively, the election of Trump is only the latest development in a global trend towards right wing populism which harnesses, but fails to address the economic, political and spiritual divides of our times - and indeed takes us backwards towards old prejudices and increasing separation. We need, but may not get intelligent and democratic government: but either way, we won't be able to involve citizens in a new dialogue without energetic civic leadership working more locally to advance a vision of well-being for all and creating the new architectures for cross-boundary collaboration suggested by Professor Hambleton's analysis - and fully illustrated in the 17 innovation stories (Copenhagen, Freiburg etc.) in his latest book.

Place based leadership is a very interesting idea and has potential not only for large and thriving cities but also of second order cities with diverse challenges of transformation. Civic leadership can help on facilitating dialogues between different groups of innovators and also between and amongst different constituents of innovation. Civil society and Third sector institutions have specific expertise but may struggle on their own if they have to invest in networking capability. We are presently exploring the possibilities and challenges of connecting city governments with corporate and community organisations using the lenses of CSR and sustainable cities in a British Academy funded workshop at Indian Instituute of Science in Bengaluru in India on 24 and 25 November.

Place based leadership includes leadership in public as well as civil society organisations. Digital technology is making it possible for such organisations to develop innovative solutions to urban well being and quality of life challenges. However, at times individual or islands of innovation do not get connected easily. Think of one group innovating on ways to improve digital inclusion (including by teaching those who presently do not use digital technologies) and another group working on improving access to finance for small enterprises run mainly by women. Professor Robin Hambleton's ideas not only lend themselves to a neat diagram but raise an important point about simultaneously developing leadership potential in the various different institutions and improving synergies between these institution all of whom have some degree of common agenda of making the city better.

In my view, the RSA Includive Griwth Commission report findings and Professor Hambleton's ideas are relevant to cities worldwide. I would be delighted to report back after the Bengaluru workshop. I am typing this while standing in the aisle on a moving train. My apologies if I have made any typos.