Most voting systems in elections, and especially in decision-making cannot embrace our human diversity. Peter Emerson FRSA argues that a modified Borda count would be more accurate and, therefore, more democratic.

The ‘Brilliant Party’ has acquired a bright, colourful property, with just one defect: the front door is Drab, very, very Drab. The three executive committee members – Ms I, Mr J and Ms K – agree, unanimously, “that’s dreadful,” says one; “yes, terrible,” “indeed, horrible.” So there is a consensus on what they don’t want, and the door must be re-painted. But what colour do they want in its stead? A debate ensues.

“Anything but Drab,” saysMs I, and shemoves a motion: “paint it Amber”. “That’s worse than Drab,” Mr Jcounters, so he proposes an amendment: “delete Amber, insert Beige”. “But Beige is bland!” opines Ms K, and she proposes a second amendment: ‘Crimson’. The committee is indeed split, and there’s no consensus on a new colour. Not yet anyway.

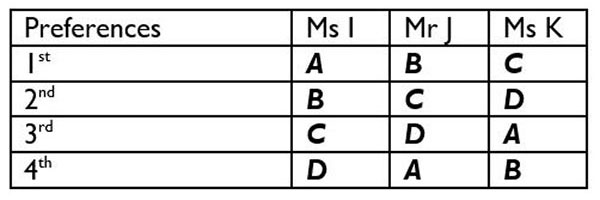

Altogether, we may observe, there are four options: A, B, C plus the status quo D, and the three members have the following preferences:

Being committed democrats, they follow standard procedure. Firstly, they choose the more preferred amendment, B or C; and a majority of two, I and Jprefer B. The next step is to see if a majority wants to use this more preferred amendment: so it is A versus B; but another majority, I and K want A, the motion unamended. Finally, it is this substantive A or the status quo D, and both J and K select D. So D is the outcome, their majority vote decision (which we call their social choice): by a majority of 2:1 or 67%, the executive committee votes to keep the door Drab, very. Democratically? Oh yes, very.

But (the table tells us), all three prefer C to D. Not just 67% but all of them, 100%, like C more than D. With binary voting, however, that which is the least popular actually comes out on top. In this example, the majority vote outcome is wrong. So here (and, we hasten to add, in many another setting), majority voting just does not work well.

As a tool for measuring opinions, binary voting is as crude an instrument as would be a Covid-19 thermometer with only two calibrations: ‘hot’ or ‘cold’. If the suspected patient’s temperature is actually normal, any and every temperature reading on such a binary device will be wrong. Well, it is not much better with binary voting and, as we have seen, the outcome of any binary decision-making process may also be wrong. A more accurate measure of an individual’s opinion is one in which he/she can express degrees of support: on any one colour for the door, is he cool, luke warm, hotly in favour, or whatever. Is B really worse than D, as Ms K suggests, and so on. If they were to use a preference points system in which a first preference gets four points, a second gets three and so on, the social choice would be C. In the above example, A is more popular than B, but so too B is more popular than C, C than D, and D than A… so no matter what the outcome, there is always a majority in favour of something else!

In a word, binary voting – this ‘good’, that ‘bad’ – is Orwellian in its simplicity. No wonder the outcomes are sometimes wrong. With preferential points voting, we get not only a social choice as the most popular option, we also get the committee’s social ranking. Binary ballots are blunt; preferential points voting is more inclusive, informative and accurate.

At the moment, in politics as well as business and the community at large, decisions are often made on the basis of binary votes, initially on amendments and then on substantive motions, and everything is done in the laid down sequence of amendment-substantive-decision (not least because, otherwise, the outcome could vary). The more accurate methodology of preferential points voting would list all the options (or on complex matters, a short list of about five of them), and allow those voting – the people in a referendum or the elected representatives in a parliament – to cast their preferences.

In a preferential points vote on three options, there are six ways of casting your preferences. With four options, there are some 24 ways of submitting a full ballot. So the voter may indeed express a more nuanced opinion. Such are the advantages of preference voting, each may express a more accurate summary of their views; and if every individual opinion is more accurate, then the collation of that data into a collective opinion may also be more accurate.

Now in some debates, there may be those who want only one particular option, no ifs, no buts, no compromise: for them, democracy is win-or-lose. So they may want to cast only a first preference and leave the rest blank. Well, in a modified Borda count (MBC), as this form of preference points voting is called, the person who votes for only one option (and says nothing about the others) gets one point for his favourite option (and nothing for the others). The one who casts two preferences gets two points for their favourite (and one point for their second preference). And those who, in a ballot on four options, cast all four preferences, get four points for their favourite, (three for their second choice and so on). The option with the most points is the winner.

So the system is inclusive. The protagonists will want as many points as possible, so not only will they want all their supporters to give their option their first preference, and to do so in full ballots; they will also find it advantageous to campaign for a second or at least a third preference amongst the other members of society. Now if everyone does submit a full ballot, the winning option, the one with the most points, is also that which gains the highest average preference, and an average, of course, involves every voter, not just a majority of them.

Majority voting is not only divisive and exclusive; as shown above with the Drab door, it sometimes produces the wrong outcome. Furthermore, while it might ratify a decision it cannot identify ‘the will of the people’ or the will of parliament, because the winning option has to be identified earlier if it is to be already on the ballot paper. This means that the author of the question – be they a dictator or a democrat – controls the agenda if not indeed the outcome. In contrast, with an MBC, those participating in the decision-making process (or their elected representatives) also play a part in drawing up the options.

For some extraordinary reason, however, nearly every country, democratic and communist alike, uses majority voting in decision-making. Mathematically, such ballots are often next to meaningless. It was used by: Napoleon in referendums, which he won, all three of them, by over 99%; by Lenin when he founded the Bolsheviks – the very word means ‘members of the majority’; and by Hitler in a two thirds weighted majority, the Enabling Act of 1933. While today, this 2,000-year-old procedure is used by Washington, Westminster, Moscow and Beijing, again, as often as not, as an instrument of control.

The British sometimes have meaningless votes as when, on Brexit, Theresa May asked the House of Commons, ‘Option X, yes or no?’ three times! Her campaigning slogan, was ‘democratic leadership’. Chinese majority votes can also be meaningless, as when Xi Jinping was elected by 2,952 votes to one with three abstentions; he uses a similar oxymoron, ‘democratic centralism’. On other voting occasions, however, the Communist Party of China methodology of majority voting has itself been a determining factor: the 1989 decision to authorise a military intervention into Tiananmen Square was taken, it is said, by a margin of just one vote.

Binary voting is ubiquitous; it is even enshrined in the North Korean constitution, both simple majority and two thirds. But it is no good. In a pluralist debate – when there are more than two options on the table – if there is no majority in favour of any one thing, there is a majority against every (damned) thing (as was the case in Brexit). This truism was first pointed out by Pliny the Younger, 1900 years ago,

Why can’t we embrace our human diversity and enjoy preferential decision-making? Many countries have multi-candidate elections. We wouldn’t want any of those ‘Candidate X, yes-or-no?’ elections, would we? Why then, in referendums and in parliamentary ‘divisions’ (as such ballots are called in the House of Commons), do we have ‘Option X, yes-or-no?’ decision-making? Why can’t we follow the science, as the environmentalist might say, the science of social choice?

In a nutshell, politicians who want to unite the party/country/whatever, should not contradict themselves by using a voting procedure, which is inherently divisive, and especially not the most divisive of all. After all, you cannot best get a consensus in a majority vote because – with so many votes ‘for’ and so many ‘against’ – it measures the very opposite, the degree of dissent. Logically, they should aim to unite the electorate in a voting procedure which is cohesive, in which those voting state not only what they want but also their compromise option(s), recognising in so doing the validity of these other options and acknowledging their neighbours’ different aspirations.

The most accurate voting systems for use in decision-making are undoubtedly the MBC and/or the Condorcet rule. The former is also non-majoritarian. It allows the voters to identify their common good, if this exists. In other words, if the MBC social choice passes a pre-determined threshold level of support, this outcome can be termed their consensus, or, if higher still, their collective wisdom.

We need more democracy, not less. The scientists know what we have to do. The computer programs have already been written. It just requires the world’s Drab politicians to restrain their lust for power, so to allow us and our representatives to be the intelligent, nuanced creatures we all are.

Peter's online event for the book launch of Democratic Decision-making Consensus Voting for Civic Society will take place on Monday 30th November, at 7pm.

Peter Emerson is the director of the de Borda Institute, an international NGO which promotes inclusive decision-making, not only in conflict zones like Northern Ireland and the Balkans, but also in (perhaps) emerging democracies like Russia and China. His latest work is Democratic Decision-making, Consensus Voting in Civic Society and Parliaments, 2020, (Springer, Heidelberg).

Related articles

-

Beyond binary ballots

Comment

Peter Emerson FRSA

Peter Emerson FRSA on why binary ballot voting should be a thing of the past.

-

Liberal democracy in the time of pandemic

Comment

Peter L. Biro FRSA

Once the pandemic is over, we must assess the abridgment of rights and freedoms which we were deemed to accede during the crisis.

-

Making deliberative democracy work

Comment

Perry Walker

In his 2018 annual lecture, Matthew Taylor called for at least three national citizens’ assemblies to be held each year on key current challenges facing the UK. Perry Walker FRSA explores how to make that a success.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.