Jean-Yves Camus is Director of the Observatory of Radical Politics at the Jean-Jaurès Foundation and an Associate Research Fellow at the French Institute for International and Strategic Affairs

Far-right parties in Europe, as well as far-right groups in the US, are often described as authoritarian movements whose only concerns are immigration, law and order, and an aggressive nationalism that rejects international regulatory agencies and agreements. Although this is partly true, climate change and environmental issues are so much at the heart of policymaking and party politics today that the far right cannot just ignore them.

Some of those parties are global-warming sceptics and think that anthropogenic climate change is a hoax; others do not deny humankind can negatively affect the climate but downplay the extent to which this has been the case and maintain a pro-industry stand, balancing a pro-climate policy against the need for continued growth and its benefits for employment. However, there are also far-right, and even radical-right, movements that promote an agenda of ecology and de-growth.

Ideological views of climate change

Global-warming sceptics, who include far-right figures such as Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro and many Trump followers within the Republican Party, are not just a threat to liberal democracy because they oppose the consensus built on the resolutions of COP21. After all, it can be argued that they are merely politicians favouring the interests of big business. But refusing to accept that anthropogenic climate change is a reality is an ideological position.

Other far-right parties, such as the Spanish Vox and the German Alternative für Deutschland, have a different approach. For them, the fact that the overwhelming majority of scientists believe climate change is man-made is not particularly important. What matters is that they see climate change as a creed imposed by the so-called elites and progressive political parties as part of a broader attempt to destroy the ‘natural order’ and ‘traditional’ values.

What can be particularly harmful for democracy is that many of those who believe climate change is a hoax will eventually support other conspiracy theories, such as the ‘Great Reset’ (the belief that the Covid-19 pandemic was orchestrated by a group of world leaders so that they could take over the global economy) and will spread their toxic message under the guise of supposedly dissident thinking.

Avocado politics

Other far-right politicians have understood the benefit they can gain from promoting a pro-environment policy, both in terms of attracting new voters and in becoming seemingly more mainstream.

The French Rassemblement national (National rally, RN, formerly the Front national), led by Marine Le Pen, has recently tried to show interest in environmental policy by adding ‘Localism’ to the salient features of its platform for the 2022 presidential election. Localism means favouring locally produced goods, including agricultural goods, over imported. But it is also deeply connected to identity issues; according to RN, buying local means boosting local employment and needs to be understood within the broader frame of the party’s protectionist agenda and its “priority to the French” motto. However, on other environment-related issues, RN has constantly disagreed with the progressive and green parties, as does the Flemish Vlaams Belang. Both parties oppose wind-powered energy, stand for the continuation of nuclear-energy production and are vocal in supporting the lobby of car owners and manufacturers who are against higher road tolls, the increase of taxes on gasoline and moving to soft modes of transportation in cities. There is little doubt that far-right parties only show an interest in ecology as a public relations strategy.

One party that has successfully integrated environmental policy with its pre-existing far-right beliefs is the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ), a former coalition partner of the Austrian People’s Party. The FPÖ affirms in its party programme that its goal is “to preserve a homeland for future generations that facilitates autonomous living in an intact environment”. It is interesting that this commitment to what can be interpreted as a green agenda is part of a paragraph in the party’s manifesto dealing with “Homeland, identity and environment”. In other words, environment is a concern for the party insofar as it goes hand in hand with nationalism and, in this case, a reminder that “the language, history and culture of Austria are German”.

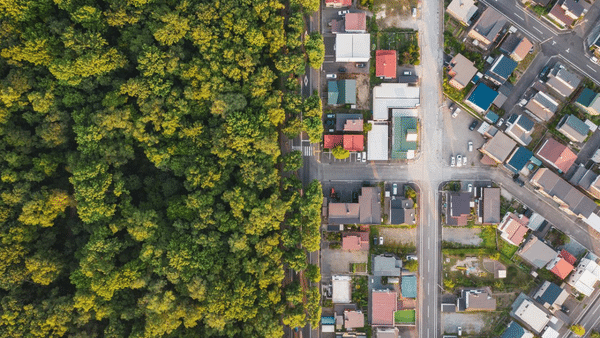

Thus the FPÖ makes it clear that, according to its ideology, there is a correlation between protecting natural resources and remaining faithful to the ethnic roots of one’s people. This is perfectly in line with the long-standing tradition of the German völkisch movement, which sang the praises of a rural life true to ‘old-time’ values, as opposed to the corrupting influence of the cosmopolitan cities, said to be a fertile ground for revolutions and subversion. From the end of the 19th century until the 1930s, the segment of the German Conservative Revolution known as Jugendbewegung drew heavily on the concept of “going back to the roots of the Nation” through exploring the rural areas of Germany and their folklore, with an emphasis on the pagan past. Some völkisch groups, such as the Artamanen, became small groups of settlers who left the cities to live on farms, and who were planning to colonise the farming lands that were to be conquered by the Third Reich, a dream that never materialised.

The ‘land’ has been connected with ethnicity by many far-right groups. Ethnonationalists have also promoted the idea of a separate homeland for white people: the South African apartheid system was intended to restrict the settlement of Black people in specific townships and Bantustans, but its Afrikaner ideologues also thought of it as a means of keeping their communities faithful to the nationalist narrative of the Great Trek and the Orange Free State. This required that Afrikaner people live in a homogeneous or predominantly Calvinist-Afrikaner area. Today, some American white nationalists promote the creation of an ‘ethnostate’ in the Pacific Northwest, along the lines of the late white supremacist Harold Covington’s concept of the Northwest Territorial Imperative.

Taken to extremes

A new issue facing democratic countries is the emergence of a small but violent minority of fringe activists who belong to the extreme right and use environmental topics to spread their openly fascist ideology. The New Zealand Christchurch shooter referred to himself as an “Eco-fascist” in his manifesto and claimed that environmentalism and responsible markets were as much a priority as ethnic autonomy and the armed fight against non-Europeans.

In a similar fashion, most of the so-called extreme-right accelerationists (who believe that western governments are so corrupt that the best thing to do is accelerate their demise through violent means) in the UK and in the US, as well as the neo-Nazi Nordic Resistance Movement (NRM) in Scandinavia, have a goal of establishing the ethnostate for whites only. However, they also fight, as the NRM puts it, for “a modern society living in harmony with the laws of nature”, meaning they support de-growth, animal rights and anything that can “promote the replacement of the materialistically wasteful mentality of our society with an ecologically sound mindset”. The intelligence community across the western world knows that the lunatic fringe on the extreme right is trying to recruit new followers by using ecological language.

The tactical use of environmental issues by the far right is part of the broader challenge to democracy that comes from nationalist, populist parties. However, we should not be blind to the fact that environmentalists associated with the radical left also pose a threat to progressive values when they engage in direct action such as sabotage of power plants, unlawful occupation of land, or what is known, especially in the US, as eco-terrorism. Such methods undermine the credibility of peaceful and democratic attempts at convincing citizens that saving the Earth requires no further delay.

However, the main political problem for those with a progressive agenda is how to counter the narrative of radical-right parties as they try to hijack environmentalist policies. Fighting climate change is first and foremost a fight for equality. We must avoid the radical right’s use of ecology to lure voters into their agenda of selfishness based on ethnicity and their fantasy of a ‘golden age’ when man and nature live in harmony on the basis of natural law.

This article first appeared in the RSA Journal Issue 2 2021.

Related articles

-

Our yes/no voting system means nothing ever happens

Comment

Peter Emerson

Climate change tells us we must cooperate or die. But where’s the cooperation between political parties? Peter Emerson suggests a radical change.

-

Design for Life: six perspectives towards a life-centric mindset

Blog

Joanna Choukeir Roberta Iley

Joanna Choukeir and Roberta Iley present the six Design for Life perspectives that define the life-centric approach to our mission-led work.

-

Rural and post-industrial perspectives on the just transition

Report

Fabian Wallace-Stephens Emma Morgante Veronica Mrvcic

This report explores how changes to the energy system could impact specific Scottish regions and bring together citizens to collectively imagine better futures.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.