Hand the company over to the workers? Madness said the critics. But Jeremy Fox’s exercise in democracy grew the business and made his former employees richer. The only problem? They had to be persuaded to take holidays

For well over a decade, I ran a management consultancy in Canada. Business literature at the time dwelled heavily on the importance of hierarchical management, with journals like the Harvard Business Review (HBR) and books by gurus like Peter Drucker in the forefront of thinking on organisational discipline. Advice on how to handle subordinates so as to maximise productivity was a common theme then and remains so today, as Jacob Rees-Mogg’s recent note to civil servants to get back to their desk reminds us.

Here is Peter Drucker, half a century ago, on who should issue the orders and who should receive them: ‘Let me make one point clear: I am convinced that, in managing the business, employees as such cannot participate. They have no responsibility – and therefore no authority.’

In a tone not so different from Drucker’s, the current edition of the HBR has a feature on counteracting the supposed inefficiencies of flexiwork by changing the mindset of employees. Manipulation, control and close monitoring of the workforce are still supposed to be among the essentials of managerial competence.

While acknowledging that senior executives have to carry the can, strictly hierarchical structures have always seemed to me implicitly demeaning to employees and, for that very reason, inefficient. I therefore decided to redefine my own role as one of leadership; to replace work hours by work objectives; and to delegate decisions to employees themselves on how to conduct the work, on individual office hours, on length and timing of vacations and so on. They were adults, after all – intelligent, educated, fellow human beings. My role in this regard was to act as backstop, to solve problems as they arose, and to provide advice as and when requested. Word of this change somehow slipped out to the press and the company became the object of a satirical article in one of Canada’s main periodicals in which the writer wondered if any of our employees bothered to show up for work.

Problems certainly arose under the new dispensation but not of the kind imagined by the satirist. Productivity soared but led to employees, conscious of their responsibilities, spending much longer at work. I ended up having to insist on them organising vacation schedules and taking time off. The business thrived and employee earnings rose.

Some years later, as chief executive of a modest UK company, I had no hesitation in adopting a similar policy. Nor was I surprised when it produced similar results. My mantra became this. Maximum agency for employees under an umbrella of direction and advice from the CEO, whose main additional responsibilities were dealing with the wider world, encouraging innovation and ensuring that customers came in through the door.

As the business grew, I began to explore the possibility of turning employees into shareholders. This was not a whim but the logical development of prolonged thinking about the strengths and weaknesses of the capitalist system. My view is that there is no such thing as a purely private-sector company owned exclusively by ‘investors’. In reality, every company is a joint venture between the state (provider of essential infrastructure, public education, security and the rest), the financial investor, and the employees. Those employees are also investors - not with money but with their time and effort, and with the skills they deploy.

The value of those employee attributes increases over time and should, in my view, be rewarded in terms of capital as well as income – just as conventional shareholders receive dividends (income) and increases in the value of their share capital as a firm grows. When firms go into decline or collapse, the same applies in reverse.

But here I came upon another problem. The creation and transfer to individuals of shares in an operating company is deemed by HMRC to be taxable to a level dependent on their value. Employees receiving shares would thereby incur a tax liability payable from their income.

To avoid this burden, I secured the agreement of the board (whose members accounted for over 50 per cent of voting rights) to create ‘shadow shares’. These were allocated on the basis of each employee’s longevity so that they could be included in the annual dividend declaration as if they were conventional shareholders. Not a perfect solution because shadow shareholders could not benefit from increases in capital value, but a lot better than nothing.

Behind these experiments in company organisation lay a determination to view employees not as subordinates but as colleagues, to listen and consult rather than issue peremptory orders, to direct with an almost invisible hand, and to share the rewards of success while providing a shield as far as possible against adversity.

As the company expanded from a handful of employees to several hundred we decided that an external examination of our quality standards would help us to avoid self-preening complacency. So we applied for and underwent the process of achieving ISO 9001 quality management certification. At the end of that process, the lead consultant told me that our organisation was amongst the best-run he had ever examined. I told him that I didn’t run the company, we all did. He replied that he had heard the same from several of my colleagues.

Jeremy Fox has been a periodical and book publisher, journalist, university teacher, artistic director of a theatre company, a British Council Overseas Career Service officer, a management consultant and a company director. He has worked for both the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs and the Canadian International Development Agency on Latin America, and has written plays and novels in Spanish and English

To correct this error:

- Ensure that you have a valid license file for the site configuration.

- Store the license file in the application directory.

Become an RSA Fellow

The RSA Fellowship is a unique global network of changemakers enabling people, places and the planet to flourish. We invite you to be part of this change.

Related articles

-

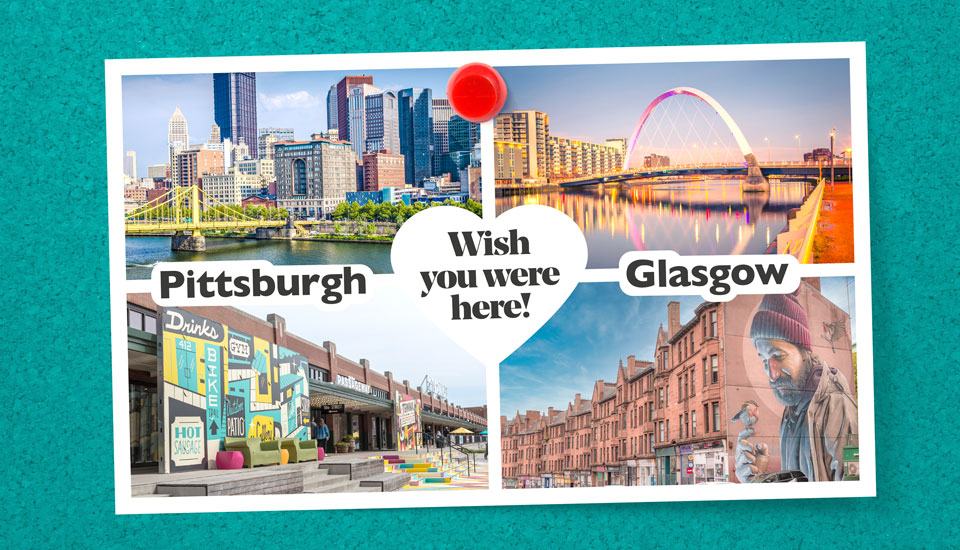

Sister Cities

Comment

Jamie Cooke Lolita Jackson Grant Ervin

Pittsburgh and Glasgow - A transatlantic relationship rooted in action and impact

-

Pressing pause

Comment

Joan P. Ball

Building resilience in advance is the key to successfully confronting adversity

-

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.