A Black food sovereignty movement in the US promotes healing and justice

“We need a r/evolution of the spirit. the power of the people is stronger than any weapon. a people’s r/evolution can’t be stopped. we need to be weapons of mass construction. weapons of mass love.” Assata Shakur, ‘We Need A 21st Century Revolution’

The question that James and Grace Lee Boggs, Detroit labour activists and organisers, would often pose to our revolutionary social movements was, “What time is it on the clock of the world?” Ecocide and genocide, 500 plus-year global colonial projects; these create a world on fire, literally and metaphorically. According to a 2021 Brookings Institute paper, even before the pandemic, economic inequality in the US had already cost $23tn over the last 30 years. Land subsidies to white settlers, one of the initial catalysts of societal inequalities enacted almost 160 years ago, reverberate to unconscionable land access and ownership realities today. Over 12m acres of Black-owned land has been stolen in the last century. Based on the 2017 US Census of Agriculture, approximately 48,000 Black farmers own 4.7m acres of farmland in the US, about 0.5% of the country’s total farmland. Of the 3.4 million US ‘producers’, Black farmers comprise 1.4% of that population. Covid-19 has both exposed and exacerbated these issues. Local economies are continuing to recover from the 22m jobs lost during the pandemic, while Black farmers received approximately 3% of the $9.2bn in Covid relief federal farm bailouts. This remains a grave injustice considering the remaining 97% was disbursed to mostly white-owned, large commodity-crop farms that already receive substantial government subsidies, among other resources. Such processes conserve inequities rather than dismantle them. These realities impact not only the pandemic of Covid-19, but the pandemic of systemic racism. Both violently prey upon Black communities in unremorseful ways.

How do we build Black food sovereignty on Turtle Island (the Indigenous name for North America prior to colonisation) when Black people own less than 1% of the land and comprise about 1% of all food producers? How do we organise in this accumulated pandemic era of food and environmental oppressions? What do we do with escalating land prices, ongoing supply chain disruptions, decline of work conditions for factory and field workers, wage thefts, job loss and the precariously inequitable health (physical, mental and emotional) conditions of our people?

We mobilise and organise against anti-Blackness and for self-determining Black life; to define ourselves, for ourselves and exert greater control over how we live our lives. We claim our indispensable role of being returning-generation farmers in an unbroken food system that is working exactly the way it was designed. To be Black and to be youth, on this time on the clock of the world, means to rebel. Systems change, from the economic to the cultural, feels possible in ways that it has not felt before. As systems of oppression become more visible, collective consciousness is becoming contagious. Social movements are growing in numbers as the world becomes more aware and more motivated to fight the bad and build a new decolonised future of the planet and humanity.

Divesting from an extractive economy and investing in a regenerative one is the mandate of this ‘critical decade’. Transition is inevitable. Justice is not.

To be a returning-generation farmer means to revalorise our cultural identities and spiritual consciousness in service to our visions of a liveable planet. As we work to capture carbon from the atmosphere and return it to the soil, we cool the planet. It is never just about growing food. Black land work is, in a dynamic intergenerational manifestation, about growing our souls to build the collective power and beloved community for our ‘survival pending revolution’, as the historical Black Panther Party articulates. We are deeply engaged in both the struggle to resist the dehumanisation of our lives and to reimagine new ways of living together in our communities. After centuries of global plunder, the profit-driven industrial economy is severely undermining the life support systems of the planet. Divesting from an extractive economy and investing in a regenerative one is the mandate of this ‘critical decade’. Transition is inevitable. Justice is not. Race, gender, class and sexuality – those most affected by the crises – must be at the centre of the solutions equation in order to make it a truly just transition. We know, as youthful students of our elders, anything ‘just’ is made possible through ceremony. We forefront ceremonial reverence of multi-species life forms (tangible and intangible) that seed the revolutions on which our very lives depend.This is the call of the land.This is the time on the clock of the world.

Building a Black ceremonial land ethic

The British Indian scholar and film maker Raj Patel cites ‘four Cs’ as the key culprits of global hunger: conflict, Covid-19, climate change and capitalism. In these times, the ‘C’ of ceremony also becomes significant to our survival, bringing the reverence needed for full revolution. We steward the land and grow food to feed our bodies as well as our starving souls. For many of us, to be Black in the world today means to be in a constant state of spiritual warfare. And, for many of us, to be Black and stewarding land is a form of spiritual worship to our Creator, our ancestors (the dead) and the earth. We (re)build topsoil and save seeds not only for biodiversity and eco-regeneration, but for the growth of our souls. It is a homegoing and homecoming, simultaneously. An unbroken circle where the call of the land is a returning to spirit that is a quintessential piece of building power.

Unlike mainstream community food systems ideologies, which assert local and sustainably-grown foods as the pinnacle to systems change, we position climate-resilient community development as a tool to build community self-determination so that we can define ourselves (our work, dreams, ideas and so on) for ourselves and exist in relative opposition to the systems that exploit and extract our people. Eating kale and going to farmers’ markets can be useful for greater health and wellbeing. But these actions do not directly build the power necessary to transform the oppressive systems at hand. We are at a pivotal point in world history where power must shift from the white and wealthy to the poor and people of colour who are most affected by systemic injustices and who have the solutions to practically transition the world so that everyone can thrive in dignity and self-determination.

Black Dirt Farm Collective

The Black Dirt Farm Collective (BDFC), a group of which I am a founding member, is a collective of mostly young agrarians guiding a political education process. Through our cultivation of an agrarian education (‘Afroecology’), we ground our work on how agrarian communities’ personal, cultural and technical capacities can be activated and used as a socially and ecologically transformative organising tool. Our collective mission is to facilitate and support socio-cultural trainings rooted in the wisdom of nature, foster intergenerational exchanges, and bridge the rural–urban generational divide. We coined ‘Afroecology’ as a process of social and ecological transformation that involves the re-evaluation

of our sacred relationships with land, water, air, seeds and food while valuing the Afro-Indigenous ways of knowing and centring the struggles of the Black experience in the Americas. Mutual aid, grower cooperative marketing formations, climate-resilient infrastructure development, political trainings and radical social entrepreneurship are our weapons of mass construction and mass love that Assata Shakur proclaims as the necessity of a 21st-century revolution.

BDFC recently purchased 9.7 hectares (24 acres) of rural land in Maryland which we envision as an engine for Black cooperative economic development. We are currently building out this space into a farm, recreational and educational event space, and private residence. In addition to building out this central site, we operate small urban farms and community gardens throughout the US Mid Atlantic, South Atlantic and Deep South regions. Given our cultural centring, we focus heavily on farming Afro-diasporic crops that illuminate our cultural histories and remain in high demand for consumption by our communities. Providing high-quality, affordable, organically grown okra, watermelon, callaloo and sweet potatoes is an important piece to the work. If we are not feeding ourselves our culture, who will? We also create value-added products to increase our profit margins, as we work to become more economically sustainable. Throughout various locations along the Atlantic coast, members of our collective sell at farmers’ markets, operate Community Supported Agriculture programmes (commonly known as ‘CSAs’), organise community food donations and collaborate on farm-to-table dinners.

Due to the enormous racial wealth gap that positions Black economic standing at stark depths compared with others, among the most effective strategies to support our work is donating money and infrastructure supports so that we can, not just survive, but thrive. We encourage our customers to pay a premium, when possible, for our products and services as an act of solidarity and working towards reparations for the multi-century theft of Black labour in the building of the US empire and accompanying colonies. We believe in transforming our agrarian work cultures by paying ourselves and our collaborators liveable wages for work that is often undervalued and denigrated by industrial society.

This is the (re)cultivation of Black agrarian politics. It begins with the study of African diasporic spiritualities and nature, Black agrarian history and various political ideologies that inform how we reframe the narrative around land and agriculture within Black experiences. Ongoing evolutions of Black exploitation has led us to confuse “what happened on the land, with the land itself,” as Leah Penniman from Soul Fire Farm states. Violent white terrorism against Black farming communities has strategically strangled our connection to and physical presence on the land. Creative cultural expressions such as hip hop, spoken word, visual arts, and various dance forms are all imaginative modes we use to decipher and heal our relationship to land, and our imaginations are grounded in ‘the spirit’ that sustained us throughout centuries of cultural disruptions, geographical displacements and social dispossessions.

Youthful possibilities

As the Black writer and activist James Baldwin says, “the least we can demand is the impossible.” According to Afrofuturist fiction writer, Octavia Butler, “we can…do the impossible as long as we can convince ourselves that it has been done before.” This is the youthful mandate of our times, to ensure there is a liveable planet for us and future generations. In this ‘critical decade’ we have no more time to waste. We build our collective power through the construction of deep accountable and trusting relationships to one another. We do it through working in reciprocity to sustain authentic democratic structures. We do it through reviving kinships with Indigenous peoples on Turtle Island. And, of course, we do it through growing food and the infrastructure needed to thrive in a Black self-determining reality. A Black ceremonial land ethic pollinates our multi-generational survival and power. It ensures the possibilities of youth now and yet to come.

Shakara Tyler is a returning-generation farmer, educator and organiser who engages in Black agrarianism, agroecology, food sovereignty and climate justice as commitments of abolition and decolonisation. She serves as Board President at the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network, board member of the Detroit People’s Food Co-op and co-founder of the Detroit Black Farmer Land Fund, and is a member of the Black Dirt Farm Collective

To find out more, visit: facebook.com/blackdirtfarmcollective

This article first appeared in the RSA Journal Issue 2 2022.

Related Comment articles

-

Worlds apart

Comment

Frank Gaffikin

We are at an inflexion point as a species with an increasing need for collaborative responses to the global crises we face.

-

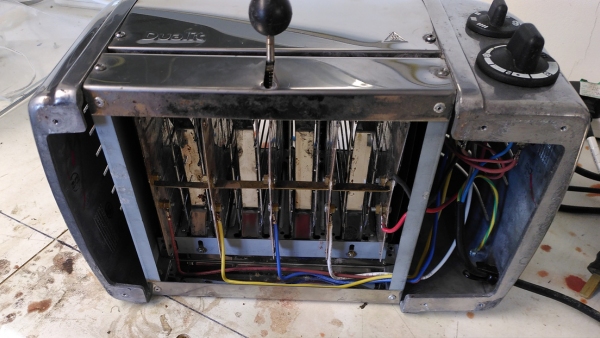

Why aren't consumer durables durable?

Comment

Moray MacPhail

A tale of two toasters demonstrates the trade-offs that need to be considered when we're thinking about the long-term costs of how and what we consume.

-

You talked, we listened

Comment

Mike Thatcher

The RSA responds to feedback on the Journal from over 2,000 Fellows who completed a recent reader survey.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.