Does the online world really offer young women and girls more power than ever before?

Sidelined on the basis of gender and age, girls and young women historically held little influence in society at large. On the surface, social media has changed this. On platforms like Instagram and TikTok, gender and age no longer appear to be barriers to gaining influence and may even be an advantage. But does influence online translate into increased power in the world?

The influencer as activist

On 11 March 2020, just days before cities like London and New York went into lockdown for the first time, 17-year-old Swedish climate change activist Greta Thunberg called on young people worldwide to abandon their plans for in-person school walkouts to mark the first anniversary of the Climate Strike. As an alternative, she urged them to engage in an online protest using her newly launched hashtag #ClimateStrikeOnline. A year earlier, Emma Grey Ellis, a staff writer at WIRED, had described Thunberg as “evidence of a changing culture of digital activism, one that’s skewing younger and younger every time adult-run institutions get stuck in political gridlock.” Still, in the end, it wasn’t Thunberg’s activism that would dominate headlines during the Covid-19 lockdown, but rather the activism of another 17-year-old girl, bolstered by little more than a cell phone, Instagram account, and her own tenacity and courage.

In March 2020, Darnella Frazier was unknown to most people outside her immediate community. Her life could not have been more different from Thunberg’s. While Thunberg was travelling around the globe (on a yacht, to avoid contributing to climate change) meeting with world leaders, Frazier was attending Roosevelt High School, a public school serving the Powderhorn Park neighbourhood in Minneapolis. Then, two months into the pandemic, Frazier’s life took a sudden and dramatic turn.

On 25 May, Frazier took her nine-year-old cousin to a local convenience store to purchase a treat. Outside, Frazier spotted the police restraining a man on the pavement. She started filming the incident on her phone. Twenty seconds into the recording, the man – who the world would soon come to know as George Floyd – said, “I can’t breathe.” The video, which lasted 10 minutes, clearly showed Derek Chauvin, then a Minneapolis police officer, kneeling on Floyd’s neck until he stopped breathing. Frazier kept filming the incident until Floyd’s dead body was carried away on a stretcher. When Frazier got home, she uploaded part of the video to her Instagram account. The video went viral and, over the coming weeks, people across the United States and eventually worldwide took to the streets in protest.

Social media has not given girls like Frazier or Thunberg a voice; girls have always had a voice. But these platforms have offered a convenient – and free – way to amplify their voices, which until recently have all too often been muted. The difference is especially striking in Frazier’s case. Given that the terrain upon which knowledge claims are assessed is structured by gender, age and race, without the benefit of video documentation Frazier’s eyewitness account would likely have been met with scepticism, if not outright hostility. Armed with a mobile device and Instagram account, Frazier had the proof she needed to influence the perspectives of people around the world. Social media is not responsible for the Black Lives Matter protests that took place globally following the death of George Floyd but, without such platforms, Frazier’s ability to intervene and subsequently spur this action would have been unlikely.

For every girl like Frazier, who was awarded a 2021 Pulitzer Prize Special Citation for “courageously recording” George Floyd’s murder, and Thunberg, already a two-time Nobel Prize nominee at 19, there are also hundreds of thousands more whose names we may not recognise but who are also using social media to wield influence on the world. One of the most notable interventions being spearheaded by girls and young women on social media platforms, which was emerging pre-pandemic but expanded considerably during lockdown, are peer-led movements to address young people’s mental health. These girls and young women seem to intuitively understand that they no longer need to wait for adults to fix systemic problems or build services on their behalf since they now have a platform to do this work themselves.

Still, Frazier, Thunberg, and their lesser-known counterparts who are using social media platforms to drive social change may not be the majority. Most girls and young women who have influence online or aspire to have it are not spearheading political movements or tackling mental health issues. More often than not, girls’ and young women’s quest for influence seems to take a very different form.

The influencer as entrepreneur

I recently read a feature-length article about a former student of mine who I’ll call Lily here. I learned that Lily had just purchased a loft in Manhattan and hired an interior designer to furnish it with unique items, including a $20,000 sofa. I also learned that this loft was not only Lily’s first real estate purchase but might ultimately serve as her retirement home; flush with cash, she plans to retire in five years. I would be surprised to read this story about any of the students I’ve taught since the late 1990s. What made this story even more remarkable is that Lily is part of Generation Covid.

Like many of her peers, Lily spent over a year and half studying on Zoom, which is where I met her in early 2021. But unlike most of my students, who generally introduce themselves by identifying their major and clarifying their preferred gender pronouns, Lily introduced herself to the class as “a rising influencer on TikTok”. What I did not know at the time was that Lily, who often spent my Zoom classes frantically tapping away on her phone rather than engaging in class discussions, was on a mission. She wanted to become a ‘verified influencer’ (achieved when a social media platform confirms that you are who you claim to be) and a ‘mega-influencer’ (someone with over 1 million followers) before her graduation in May. To achieve this goal, during her final semester of university, she committed to posting 20 to 30 videos a day on TikTok. Unlike many influencers who have a specific focus (make-up tips, fitness and so on), Lily posts videos about whatever she happens to be doing at any given time. As a young, thin, white woman, Lily – or more specifically, her body and the things she does to maintain this body – is the content. Still, it would be remiss to diminish her success. If Lily has turned her life into a reality TV show, she is more than its starring actor; she is also the director, editor, producer and publicist.

Lily’s online influence is also having a clear material impact on her life. After all, what says ‘I’ve made it’ more than a $20,000 sofa sitting in a spacious loft in one of the world’s most expensive cities? But do girls and young women like Lily who amass incredible influence online also have more power offline? Is their influence fundamentally changing their status in the world at large or just within the sphere of influence they create, at least temporarily, on specific social media platforms?

Online influence is acquired on platforms where girls and young women are welcome as guests but still not welcome as owners

The pursuit of influence and its cost

Thunberg, Frazier and ‘Lily’ are a study in contrasts. These young women, now between the ages of 19 and 22, have very little in common beyond the social media platforms they have each successfully deployed. They are also living proof of how these platforms are transforming girls’ and young women’s lives. There has been no other point in history when this demographic has been so easily able to influence politics and culture or obtain wealth. Focused on these achievements, it is tempting to conclude that this is a sign of girls’ and young women’s growing influence and power in the world, both as changemakers and as producers and consumers. Unfortunately, while influence is theoretically something one can acquire for free or at least with little overhead (all you need is a phone and WiFi connection), it does come at a cost, one which may be especially high for young women.

Like anyone who posts online content, girls and young women inevitably sacrifice their labour, time and privacy. Often, they give up much more. In Lily’s case, acquiring influence has required her to expose nearly every part of her body and most details of her life to more than 1 million followers. But the sacrifice does not appear to be a deterrent to the pursuit of influence. One recent US study found that, given the opportunity, over half of young Americans would become an influencer.

In May 2021, Frances Haugen, a product manager at Facebook (recently rebranded as Meta), quit her job, but not before downloading thousands of internal documents. Among the documents was damaging evidence that the company has known for years that its apps, including Facebook and Instagram, are negatively impacting young people, particularly girls and young women. Haugen’s trove included a Facebook study that found that 66% of teen girls (compared with 40% of teen boys) experience negative social comparison while using Instagram. As Haugen explained in her October 2021 testimony to the US Congress, Facebook has long known that its algorithms are likely contributing to the problem since they are designed to expose users to content to which they are already latching on, and in the case of girls, this is often “more and more content that makes them hate themselves”.

The girls and women of Generation Covid, though, are particularly exceptional. They appear to have acquired a level of influence in the spheres of politics, culture, and business that would have been difficult, if not impossible, for previous generations to acquire or even fathom. Yet, this doesn’t necessarily mean that their overall social status is better than that of previous generations.

Social media has enabled girls and young women to gain visibility beyond the bedroom cultures and mall cultures to which they once seemed confined. In this context, visibility is conflated with ‘influence’. The problem is that online influence isn’t necessarily tantamount to influence offline, where influence and power have generally been viewed as synonymous. Online influence is acquired on platforms where girls and young women are welcome as guests but still not welcome as owners. They are guests who are encouraged to linger because they happen to create great content – the type that fosters engagement and is frequently reposted, which is precisely what fuels social media companies’ profits.

Translating this influence into power in the world at large – and ensuring it extends to all girls and women, not just those who users want to look at – will not happen automatically.

It will be contingent on moving from the highly visible role of content creators to the much less visible and more integral role of platform builders and owners. Until then, the girls and young women of Generation Covid may have influence online, but in the world at large, their influence and power will remain tenuous.

Kate Eichhorn is Associate Professor and Chair of Culture and Media Studies at the New School, New York

This article first appeared in the RSA Journal Issue 2 2022.

Related Comment articles

-

Worlds apart

Comment

Frank Gaffikin

We are at an inflexion point as a species with an increasing need for collaborative responses to the global crises we face.

-

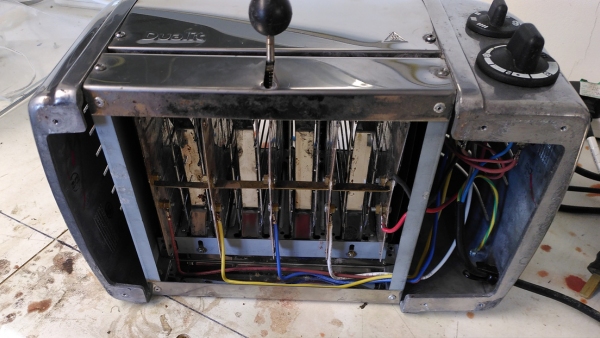

Why aren't consumer durables durable?

Comment

Moray MacPhail

A tale of two toasters demonstrates the trade-offs that need to be considered when we're thinking about the long-term costs of how and what we consume.

-

You talked, we listened

Comment

Mike Thatcher

The RSA responds to feedback on the Journal from over 2,000 Fellows who completed a recent reader survey.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.