A decade ago, a container shipping worker had an epiphany, and it caused him to question the very basis of his business. Sam Bliss and Chris Oestereich take up the story.

Ten years ago, Andrew Moore lived in Costa Rica, where he worked in maritime shipping for Dole. He was watching footage of a mammoth new ship, the world's largest at the time, which could hold more than 9,000 containers.

Ensuring those containers were full was Andrew’s job. But, as he says now: "All that merchandise had to be made of something that had to come from somewhere."

Everyone in his industry assumed ships would continue growing and multiplying. And they have. The Ever Given spent a week wedged in the Suez Canal in 2021. It is one of 91 vessels that can hold more than 20,000 20ft containers. In 2021, the Ever Ace, currently the world’s largest container ship, launched with the ability to hold 24,000 containers.

These expanding ships are the result of our obsession with growth. Since the 1970s, producing $1 worth of economic output has meant extracting about 1kg of materials from the Earth (based on The World Bank's global GDP data and the UN Environment Programme's resource use data).

In 2017, the world economy extracted 92 billion tons of materials. If we were to ship that much stuff, it would fill six billion 20ft containers loaded to maximum capacity, equivalent to nearly 250,000 loads on the Ever Ace.

Digital technologies promised a weightless, dematerialised economy, but it turns out the internet is quite material. It lives in air-conditioned warehouses full of computers, often with a coal- or gas-fired power plant next door.

Carbon emissions have risen steadily with GDP. After all, engines must burn fuel to extract, transport, and process all those materials (including fuel itself) into products.

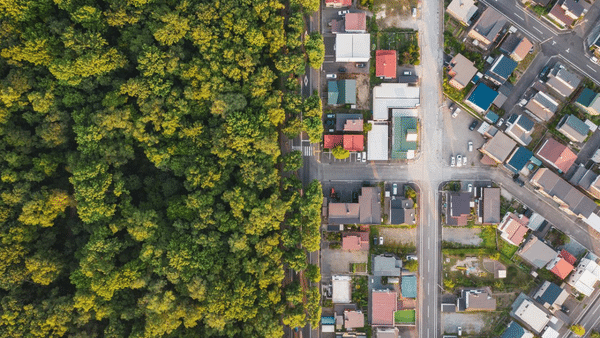

So, as the global economy has grown, physically and monetarily, humanity has turned more of the planet into mines, farms, and clear-cuts. Industry has polluted and destroyed the homes of the rural poor and the habitats of other species. As Andrew realised, materials all come from somewhere.

Degrowth now

After leaving shipping, he came across the idea of degrowth, the intentional reduction of resource use.

In practice, it means slowing the material throughput of rich countries. We extract 30 tons of materials each year to support the consumption of the average American. That’s 82kg of fuels, minerals, crops, and timber taken from the land per day to feed, clothe, comfort, and entertain each person. It's more than anyone’s fair share, and more than the planet can sustain.

But since material use and GDP are intimately linked, physical shrinking would probably bring economic shrinking. Thus, degrowth must involve reorganising society to meet people’s basic needs regardless of what happens with GDP, so the economy can decelerate justly, without the suffering recessions bring.

This sometimes causes confusion. To be clear: degrowth is not about decreasing GDP. And it’s not about reducing every person’s individual resource use (poor people might need more resources to meet their needs). Instead, it's the hypothesis that radically reducing environmental damage and carbon emissions – and making other changes in the direction of sustainability and justice – entails producing and consuming less overall. That reduction needs to focus on today’s sources of overconsumption, primarily by rich countries.

Take a hypothetical moratorium on new fossil fuel extraction. Ending fracking, drilling, and coal mining might be our best shot at saving the stable climate, and it would likely mean wealthy nations like the UK would not be able to keep expanding their economies year after year.

Degrowth data and the 2°C threshold

The latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change cites studies showing that ‘only a GDP non-growth/degrowth or post-growth approach’ can limit warming to 2°C without deploying risky or imaginary ‘negative emissions technologies’. That two-degree target is the maximum global temperature increase to which human societies are thought to be capable of adapting, but there’s no guarantee that we’ll be fine if the planet warms that much. The less warming, the better our chances.

Similarly, the 2021 Nature article '1.5 °C degrowth scenarios suggest the need for new mitigation pathways' reported results from modelling pathways for stabilising the climate. It found that ‘degrowth scenarios minimize many key risks for feasibility and sustainability compared to technology-driven pathways’. Scientists are telling us that continued economic growth puts humanity’s future in question and that pinning our hopes on maintaining a growing economy by way of tech that has yet to be realised is fraught with risk. So whether degrowth sounds unreasonable or unrealistic, the facts remain. Unless we want to take a roll of the dice with our future, we need a quick transition to a smaller economy that runs on low-carbon energy.

The IPCC also draws on research demonstrating that people can live well without growth, writing that ‘degrowth pathways may be crucial in combining technical feasibility of mitigation with social development goals’.

We need economies that can handle contraction, and we need them now.

Policies for ending our dependence on economic growth include reducing working hours and providing universal access to necessities like housing and healthcare. Recessions leave workers unemployed, without wages for buying essentials. To degrow equitably, governments need to guarantee people a job or food and shelter.

Often people are already imagining it but have never heard of the idea or the movement around it.

Degrowth and public discourse

Luckily, degrowth is gaining momentum. At least 20 books have addressed it since 2020, it’s making headlines, and the EU recently held a conference on the topic of going beyond growth, deliberately held on the 50th anniversary of the publication of the Club of Rome’s Limits to Growth report.

Now, Andrew Moore is a 54-year-old Master’s student in one of the world’s first degrowth academic programs. Like Andrew, many people have instinctively grasped the wisdom of the concept without hearing of the idea of the movement around it. And those of us working in the field know that degrowth resonates. But we cannot leave it up to chance that Andrew and people like him happen to stumble across this world-changing idea. We have to start talking about degrowth and making it happen. Otherwise, we'll continue launching bigger ships.

Chris Oestereich runs Linear to Circular and Morph, a combined circular economy consulting and upcycling social enterprise, and he’s a co-founder of the Circular Design Lab. Sam Bliss teaches ecological economics at the University of Vermont and is president of DegrowUS.

Become an RSA Fellow

The RSA Fellowship is a unique global network of changemakers enabling people, places and the planet to flourish. We invite you to be part of this change.

Related articles

-

Our yes/no voting system means nothing ever happens

Comment

Peter Emerson

Climate change tells us we must cooperate or die. But where’s the cooperation between political parties? Peter Emerson suggests a radical change.

-

Design for Life: six perspectives towards a life-centric mindset

Blog

Joanna Choukeir Roberta Iley

Joanna Choukeir and Roberta Iley present the six Design for Life perspectives that define the life-centric approach to our mission-led work.

-

Rural and post-industrial perspectives on the just transition

Report

Fabian Wallace-Stephens Emma Morgante Veronica Mrvcic

This report explores how changes to the energy system could impact specific Scottish regions and bring together citizens to collectively imagine better futures.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

Hi Chris and Sam, Good to see a Degrowth article within the RSA. You might like my Framework for Maximum Mitigation https://poemsforparliament.uk/framework Also the possibility of using fiduciary finance to facilitate a Universal Basic Provision https://medium.com/@barbarawilliams1/fiduciary-funds-for-global-ubuntu-ef4c5eb3e2f1