Could citizens’ assemblies present a new model for the future of political decision-making?

What is the role of political leadership in a new democratic paradigm defined by citizen participation, representation by lot and deliberation? What is or should be the role and relationship of politicians and political parties with citizens? What does a new approach to activating citizenship (in its broad sense) through practice and education entail? These are some questions that I am grappling with, having worked on democratic innovation and citizens’ assemblies for over a decade, with my views evolving greatly over time.

First, a definition. A citizens’ assembly is a bit like jury duty for policy. It is a broadly representative group of people selected by lottery (sortition) who meet for at least four to six days over a few months to learn about an issue, weigh trade-offs, listen to one another and find common ground on shared recommendations.

To take a recent example, the French Citizens’ Assembly on End of Life comprised 184 members, selected by lot, who deliberated for 27 days over the course of four months. Their mandate was to recommend whether, and if so how, existing legislation about assisted dying, euthanasia and related end-of-life matters should be amended. The assembly heard from more than 60 experts, deliberated with one another, and found 92% consensus on 67 recommendations, which they formulated and delivered to President Emmanuel Macron on 3 April 2023. As of November 2021, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has counted almost 600 citizens’ assemblies for public decision-making around the world, addressing complex issues from drug policy reform to biodiversity loss, urban planning decisions, climate change, infrastructure investment, constitutional issues such as abortion and more.

I believe citizens’ assemblies are a key part of the way forward. I believe the lack of agency people feel to be shaping their lives and their communities is at the root of the democratic crisis – leading to ever-growing numbers of people exiting the formal political system entirely, or else turning to extremes (they often have legitimate analysis of the problems we face, but are not offering genuine solutions, and are often dangerous in their perpetuation of divisiveness and sometimes even violence). This is also related to a feeling of a lack of dignity and belonging, perpetuated in a culture where people look down on others with moral superiority, and humiliation abounds, as Amanda Ripley explains in her work on ‘high conflict’. She distinguishes ‘high conflict’ from ‘good conflict’, which is respectful, necessary, and generative, and occurs in settings where there is openness and curiosity. In this context, our current democratic institutions are fuelling divisions, their legitimacy is weakened, and trust is faltering in all directions (of people in government, of government in people and of people in one another).

If the deep roots of the democratic crisis are about agency, dignity, belonging, complexity, curiosity, and trust, there is a need to develop new democratic cultures, practices, processes, and institutions that help enable all those things.

We need deliberative spaces that allow people to truly listen to one another and to be heard, to recognise and acknowledge each other, even in difference, to grapple with complexity and spark curiosity – in ideas as well as in why others believe what they do; to have empathy and also to be able to do the hard work of finding common ground on the shared challenges we face.

This is why I have become convinced of the power and value of citizens’ assemblies in creating the epistemic conditions for diverse and broadly representative groups of people to be able to consider complex policy and political issues, and to find common ground for the common good.

A longer view

I once viewed citizens’ assemblies as a necessary complement to strengthen representative democracy as we conceive of it today. However, conducting a deeper analysis of hundreds of assemblies when I was at the OECD, and being involved in the design of the world’s first permanent citizens’ chambers with people selected by lot, changed my perspective. The more fundamental issue is that a system defined by elections, with political parties and politicians, is designed for short-termism, for debate, for conflict and for polarisation. It puts re-election goals and party logic ahead of the common good. Adding on new forms of democratic institutions like citizens’ assemblies to an electoral system does not address the underlying democratic problems of an elections-based system.

The locus of power needs to shift

We have a wealth of evidence today that citizens’ assemblies are effective and democratic – leading to better decisions by leveraging our collective intelligence – and that they are fair and legitimate, recognising people’s agency and establishing political equality. But one-off assemblies are not changing the system. There is a need to shift political and legislative power to institutionalised citizens’ assemblies so that they can eventually become the heart of our democratic systems, defining a new democratic paradigm.

When citizens’ assemblies are taking place on all sorts of issues, at all levels of government, and everybody has the civic privilege and responsibility of being an assembly member at some point in their lives, then we will have another kind of democracy. Building new deliberative institutions that are empowered can lead to a transformative change of our democratic culture, practices and collective decision-making mechanisms.

We need deliberative spaces that allow people to truly listen to one another and to be heard, to recognise and acknowledge each other

Does this mean we only need citizens’ assemblies? Of course not. Assemblies need to be connected to more participatory and direct forms of democracy, and a place remains for institutions where people are selected by election or appointment. But there is a compelling argument for why citizens’ assemblies should be at the heart of the democratic system, defining a new democratic paradigm of sortition and deliberation, in the same way that the old paradigm is defined by elections, even though they are not the only governance mechanism that is in place.

Leading questions

If we accept the premise that a new democratic paradigm is defined by new institutions with everyday people selected by sortition, rotating their responsibility to represent others and be represented in turn, and deliberating to find common ground, there is an important question about what political leadership means in this context. It might look like stepping back, acknowledging that politicians don’t know it all, making room at the table, sharing decision-making power with citizens and creating conditions for collective intelligence to thrive.

What is the role of political leaders today to usher in and steward this change?

This change is already under way, led by the most innovative and forward-looking leaders, who recognise that the role of politicians and elected institutions today is evolving. The hundreds of examples collected by the OECD were all initiated by people in positions of power, with authority to act on citizens’ recommendations.

The world’s first institutionalised assemblies were also initiated by politicians. The world’s first permanent citizens’ chamber in Ostbelgien, the German-speaking Community of Belgium, was created through the initiative of the president of the parliament and president of the government (from two different political parties), and was established through a unanimous vote in parliament, across the six party lines.

Furthermore, the many national-level assemblies, such as Ireland’s recurring assemblies, most recently on drug policy reform, biodiversity loss, devolution and gender equality, as well as France’s assemblies on end of life and climate change, are also being driven by the elected officials in charge. Another approach is one taken by the Agora party in Belgium, whose sole programmatic focus centres on maximising deliberation, both internally and externally – shaping its decision-making on key issues by convening sortition-based deliberative assemblies to inform its policy stance. While Agora faces some tensions promoting deliberative ideals within the constraints of a dominantly electoral system, analysis suggests that this approach has led them to simultaneously reject and compete within the system, and it could also be another way forward for political leaders wanting to advance deliberative democracy within the constraints of the status quo.

Public demand for this change is also a driving force for a new relationship between politicians and citizens. Polling by Pew Research Center has found that, on average, 77% of respondents in France, Germany, the UK and the US think it is important for governments to create citizens’ assemblies where citizens debate issues and make recommendations about national laws. According to a poll by OpinionWay and Sciences Po, 63% of people in France, Italy, Germany and the UK want the recommendations of citizens’ assemblies to be binding.

What can be done to help prepare a new generation of leaders for the next democratic paradigm?

Practising democracy

The notion of political leadership discussed here is rather different from traditional conceptions of it, which tend to emphasise an individual or a party’s ability to mobilise a ‘base’, the charisma needed to ‘win’, and a full programme of policy proposals. Finding common ground, stewarding a process which involves a wider portion of the population, and not claiming to have all the answers is the opposite of that. The broader question of how to encourage such a new conceptualisation to take hold has different layers to it, related to those currently in power, as well as future leaders in the next decades. For those currently leading, some of the simpler and most effective actions include peer-to-peer exchanges with those leading the most innovative efforts, as well as ‘study trips’ to witness and observe citizens’ assemblies in action. Political parties could also adopt the democratic practices of decision-making by sortition and deliberation internally, to familiarise themselves with these concepts in practice, and incorporate them into their process for platform and policy agenda creation.

To reach future generations, there is often talk of ‘civic education’. The practice of democracy offers the most promise, however. Replacing student council elections in schools with sortition processes can help spread the lived experience of deliberative democracy from an early age, as well as teaching about the historical and contemporary examples of assemblies with members selected by lot.

Finally, I think there is a virtuous cycle that emerges from institutionalisation itself, which helps create the conditions for new forms of leadership. Citizens’ assembly members gain agency through the process. Some go on to assume other forms of leadership in their communities, either through running for office, getting engaged in politics, starting new civil society associations, or volunteering. One of the best ways to inspire new political leadership will be through the spreading of institutionalised and empowered assemblies at all levels of governance.

Claudia Chwalisz is the Founder and CEO of DemocracyNext, an international non-profit, non-partisan research and action institute, and is an Obama Leader Europe 2023. Previously, Claudia was the Innovative Citizen Participation Lead at the OECD.

Artwork by Franz Lang for the RSA. Franz is an artist and illustrator whose work has appeared in numerous publications, both in the UK and internationally.

This article first appeared in RSA Journal Issue 2 2023.

Read more Journal and Comment articles

-

Worlds apart

Comment

Frank Gaffikin

We are at an inflexion point as a species with an increasing need for collaborative responses to the global crises we face.

-

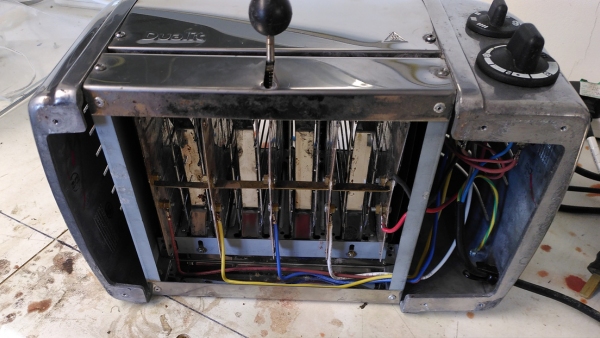

Why aren't consumer durables durable?

Comment

Moray MacPhail

A tale of two toasters demonstrates the trade-offs that need to be considered when we're thinking about the long-term costs of how and what we consume.

-

You talked, we listened

Comment

Mike Thatcher

The RSA responds to feedback on the Journal from over 2,000 Fellows who completed a recent reader survey.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

As a RSA Fellow in the US and a passionate advocate for democratic reform, I am filled with enthusiasm to see the concepts of citizens' assemblies and sortition gaining traction in discussions about political decision-making. As a US citizen, I am particularly excited about the prospect of these ideas taking root in the United States and becoming powerful tools for social change. Citizens' assemblies present a new model for the future of political decision-making, one that prioritizes citizen participation, representation by lot, and deliberation. As we grapple with questions about the role of political leadership in this new democratic paradigm, we must also consider how citizens' assemblies can connect with social movements for transformative change. Citizens' assemblies, although intended to be nonpartisan, have the potential to amplify the voices of marginalized communities when it comes to addressing the crucial issues raised by social movements. These assemblies, comprised of diverse and representative groups of individuals, have the potential to serve as platforms for marginalized communities and grassroots movements to have their voices heard. By providing deliberative spaces where people can truly listen to one another and find common ground, citizens' assemblies can bridge divides and foster understanding among different social groups. Imagine citizens' assemblies being formed to address pressing social issues such as racial justice, climate change, income inequality, or healthcare access. By bringing together community members, activists, experts, and policymakers, these assemblies can serve as catalysts for meaningful dialogue, collaboration, and the development of progressive policy solutions. For social movements seeking change, citizens' assemblies offer an avenue for their voices to be amplified and their concerns to be addressed. Through the inclusive and deliberative nature of these assemblies, social movements can engage with a broader range of stakeholders, challenge existing power structures, and push for systemic reforms. Moreover, citizens' assemblies can act as a counterbalance to the influence of money and special interests in politics. They provide an opportunity for everyday people, who are often underrepresented in traditional political processes or by the major parties, to play a direct role in shaping policies that affect their lives. By involving citizens directly in decision-making, citizens' assemblies empower social movements to push for progressive policies that prioritize the needs and aspirations of the many, rather than the few. To fully realize the potential of citizens' assemblies in driving social change, it is crucial to connect them with existing social movements and grassroots organizations even while remaining nonpartisan. Cross-pollination between social movements and citizens' assembles is possible. Social movements can provide valuable insights, expertise, and mobilization capacity, while citizens' assemblies can offer a deliberative space for these movements to refine their strategies, build alliances, and develop policy recommendations rooted in the collective wisdom of the participants. As a progressive activist, I am inspired by the possibilities that citizens' assemblies hold for forging a more inclusive, equitable, and just society. I am eager to collaborate with social movements in Tennessee and across the United States to advocate for the establishment of citizens' assemblies that address the pressing issues our communities face. By connecting citizens' assemblies to social movements, we can harness the power of collective action, foster meaningful dialogue, and work towards a future where the voices of the marginalized and oppressed are heard and acted upon. Let us seize this moment to create a democratic landscape where citizens' assemblies and social movements come together, amplifying each other's efforts and driving the transformative change we so desperately need. By building bridges between citizens' assemblies and social movements, we can build a more participatory and responsive democracy that truly serves the needs and aspirations of all Americans. Together, we can shape a future where justice, equity, and progress are the guiding principles of our political decision-making processes.