First Past the Post might work in horse racing but it is not fit for purpose as an electoral system, argues the CEO of campaign group Best for Britain.

A little bit of ignominious history was made at Towcester Racecourse in March 2011, when no horses finished the 4.25 steeplechase.

Of the four entries, two fell at the sixth fence and two came to grief at the final hurdle, leaving astonished punters with exactly no gee-gees to cheer over the finishing line.

Because nobody reached the finishing post, the race was declared void and – here's a thing – everybody got their money back from the bookies.

In the world of horses, first past the post (FPTP) means just that. Getting to within a furlong of the finish and then expiring counts for nowt, even if you were the last gelding standing. Politics, of course, purloined FPTP from the racing fraternity and applied it to the outdated electoral system which still blights general elections in Britain, among other places.

The arguments against FPTP are many. It imposes minority rule (in 2019, the Conservatives won 56% of seats with only 43.6% of the vote) and squeezes out smaller parties (the Liberal Democrats, Greens and Brexit party gained 16% of votes combined but only 2% of seats). And votes are not equal. Because of the way voter groups are concentrated, in 2019 the SNP and Sinn Fein won one seat for every 26,000 votes they attracted. The Conservatives won one seat for every 38,000 votes they received, but Labour needed 51,000 for one seat and the Greens needed 866,000.

FPTP is also a misnomer: there is no post to pass. A party might gain power with 35% of the vote (2005) or 48% (1966). What you’ll struggle to find is a party that gains power with 50% or more of the vote (excluding coalition deals).If this makes you feel uneasy, you are not alone. Political parties know FPTP is not fit for purpose and, tellingly, none of them uses it for their own leadership contests.

As an alternative, there are various forms of proportional representation and, while it’s hard to argue that any is perfect, it’s harder still to argue that they are inferior to FPTP. They all seek to allocate votes fairly and to ensure everybody’s vote counts – something that FPTP fails to achieve.

FPTP disenfranchises voters, and it does so extremely effectively. Major parties can ignore safe seats, with resources focused on key marginals, making it even more likely that smaller parties will be squeezed out in these areas. The public was asked to vote on replacing FPTP with an alternative vote system (which itself is not proportionate) back in May 2011. Almost 68% rejected it. But public opinion has shifted markedly in recent years, possibly because of frustration with the present system.

In the end, FPTP will go, because upcoming generations will view the disenfranchisement it imposes as disparagingly as previous generations viewed the disenfranchisement of working men and women, and history will likely view the reformers kindly.

As for those who have the opportunity but lack the courage to abandon FPTP – if they are remembered, it will be for flogging a dead horse.

Naomi Smith is CEO of the campaign group Best for Britain

This article appeared in RSA Journal Issue 2 2023.

Read more Journal and Comment articles

-

Worlds apart

Comment

Frank Gaffikin

We are at an inflexion point as a species with an increasing need for collaborative responses to the global crises we face.

-

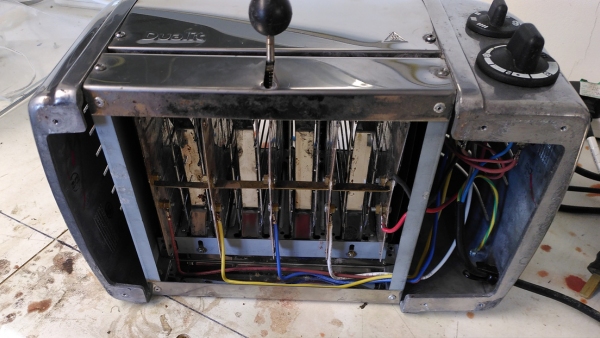

Why aren't consumer durables durable?

Comment

Moray MacPhail

A tale of two toasters demonstrates the trade-offs that need to be considered when we're thinking about the long-term costs of how and what we consume.

-

You talked, we listened

Comment

Mike Thatcher

The RSA responds to feedback on the Journal from over 2,000 Fellows who completed a recent reader survey.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

This article rehearses briefly some of the arguments against FPTP, but doesn't convince me, because it fails to address explicitly the question of what we actually want or need from an electoral system. It makes the assumption that "making everyone's vote count" is a key requirement, but in any system with free and fair elections many people will vote for unsuccessful candidates. Even in full proportional representation some parties will not be part of the governing coalition. So the alleged "disenfranchisement" of those who vote for losing candidates in FPTP is in fact an inevitable feature of all voting systems. Incidentally, the article has been on the RSA website since 29 June, and I am the first to comment on 25 July, so perhaps FPTP is not the burning issue for the public that the author suggests. Or is it just that those who have been most vociferous against FPTP in the past support parties which now look like benefiting from it at the next General Election?