One organisation’s blueprint for engaging young people in the political process.

One of the key questions at the heart of our politics is how to create a democratic system that does not just create opportunities for all citizens to engage, but one with which all citizens choose to engage. Persistent inequalities still dictate who takes part in our democracy. People who rent their homes, people with disabilities, low-income or minority ethnic communities and young people are all less likely to be included on the electoral register. In the 2019 general election, 47% of 18- to 25-year-olds voted, compared with 75% of those 65 and older.

Thankfully, the worn narrative that young people are apathetic towards politics has largely disappeared. Young people’s commitment to Black Lives Matter and the School Strikes for Climate, for instance, has demonstrated their willingness to engage and their knowledge of social and political issues. Yet, young people remain largely disengaged from traditional political systems. While this is partially due to the way these systems communicate and engage, often using impenetrable language and traditions that feel alien or outdated, even the removal of these barriers reveals a more fundamental issue: a breakdown in the relationship between politicians and young citizens.

Here at The Politics Project, we have been working for eight years to understand and improve the relationship between young people and politicians, including through our flagship programme, Digital Surgeries. The programme’s ambition is simple: we want every young person to have a meaningful conversation with a politician during their time at school. Currently, only 5% of young people engage with a politician during their time in education, rising to about 12% for privately educated students. We address this gap by creating these opportunities. To date, we have supported over 500 conversations between 300 politicians and 10,000 young people from over 400 schools across the UK.

Digital Surgeries supports groups of 10–30 young people to have an hour-long video call with a politician who represents them. Crucially, young people are supported (through workshops in school) to prepare for the meeting by learning about the guest politician and crafting relevant questions to ask. This helps them feel informed and in control, producing more meaningful interactions from which both sides benefit.

We work with all levels of politician, from local councillors to cabinet ministers. We also work with politicians from all political parties, helping to expose young people to points of view they may not have encountered before. While most Digital Surgeries involve young people speaking to the politician representing their ward or constituency, we have also supported them to give evidence to parliamentary select committees, providing a rare chance for parliament’s work to be informed by the young people it represents. We are in the process of rolling out a version of the programme in Welsh schools, funded by the Welsh government, and we also support US politicians to engage with UK students.

We believe these engagements act as a ‘civic inoculation’, empowering young people to feel comfortable contacting a politician later in life and serving as a counterweight to the stereotype that all politicians are corrupt or ‘in it for themselves’. Our work does not and is not designed to create an uncritical view of politicians. Rather, it humanises them, makes them more approachable. It shifts the idea of political institutions as a set of arcane rules and distant buildings to a (far more relatable) collection of individuals. One student commented they were surprised that the politician they spoke to was “just like us and not posh”.

What’s more, the process of preparing for and undertaking these meetings creates numerous benefits for young people, including building political knowledge and understanding, improving speaking and listening skills, and boosting confidence.

Part of the problem is that our democratic systems have not kept pace with technological change

Our evidence also shows us what works for building relationships and trust. For example, the most impactful engagements are those that feel informal, are led by young people, and take place in small groups. Our evaluation data shows that young people in groups of fewer than 20 are 15% more likely to trust the politician with whom they are speaking, while those in groups of over 60 are 4% less likely.

We also know that an effective way for politicians to build trust is to take action on behalf of the young people they meet and speak with. This could range from making sure a broken streetlamp gets fixed to raising a relevant issue in parliament.

The Politics Project has embraced digital platforms, such as Zoom, to hold conversations between young people and politicians, finding them to be just as effective as face-to-face interactions, sometimes more so. Young people who may be nervous about speaking with a politician often find this form of communication less intimidating. It is certainly more practical, as it opens up Monday through Thursday for engagements with constituents while MPs are in Westminster and reduces the need for travel.

Many schools prefer virtual engagements, too, as this eliminates the need to ‘roll out the red carpet’ and involve senior staff in supporting a visit. Research from the University of California shows that engaging via digital platforms can help with difficult conversations, supporting participants to discuss challenging topics in a controlled environment.

These findings highlight how rarely engagements between citizens and politicians are properly designed for actually building trust and relationships. Often when politicians do interact with students, it is in school assemblies, where they speak to hundreds of students at a time. While this may engage a greater number of students, our findings suggest these mostly unilateral interactions are unlikely to result in meaningful relationship-building.

Part of the problem is that our democratic systems have not kept pace with technological change. The norms of political engagement were established pre-internet. In the 20th century of analogue broadcast media, politicians shared their ideas through speeches to live crowds or television or radio audiences, the larger the better. These formats remain the primary ways that politicians communicate with the public, regardless of the benefits of more innovative modes of engagement, including younger audiences.

What might it look like if we could shift this political culture? If an MP were to give two hours of their week to meaningfully speak to 50 disengaged constituents, they could speak to over 20,000 people in a parliamentary term, over a quarter of the average parliamentary constituency. It would require a systematic approach in which politicians reach out to constituents, rather than just engaging with those that contact them. It would also require more resources, as politicians’ offices would need help to coordinate, support and facilitate these engagements.

At The Politics Project, we are working to deliver this cultural shift. We want politicians across the political spectrum to recognise the importance of youth voice and reimagine how they engage with young people. We also want to support schools and youth clubs to do more to equip young people with the knowledge, skills and confidence to shape the decisions that affect them. In a healthy democracy this cannot be an opt-in or simply a ‘nice to have’.

Our work demonstrates the benefits of developing this more inclusive national conversation. The prize to be won is a healthier democracy, where all citizens choose to engage with political systems and everyone’s voice counts.

Harriet Andrews is the Founder and Director of The Politics Project, which supports young people to learn about and engage in democracy. She sits on the steering group for the Democracy Network and is a founding member of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Political Literacy.

Backpack styled by Vera Wachter, age 12, and Una Wachter, age 15.

This article appeared in RSA Journal Issue 2 2023.

Read more Comment and Journal articles

-

Worlds apart

Comment

Frank Gaffikin

We are at an inflexion point as a species with an increasing need for collaborative responses to the global crises we face.

-

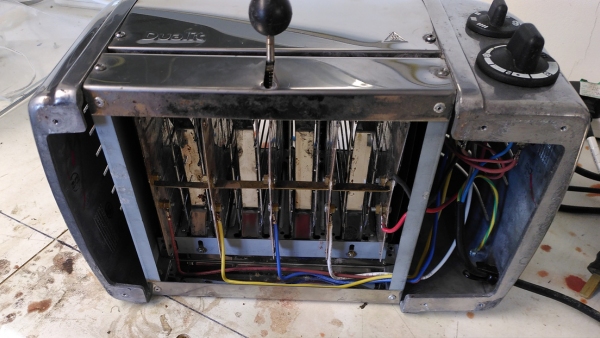

Why aren't consumer durables durable?

Comment

Moray MacPhail

A tale of two toasters demonstrates the trade-offs that need to be considered when we're thinking about the long-term costs of how and what we consume.

-

You talked, we listened

Comment

Mike Thatcher

The RSA responds to feedback on the Journal from over 2,000 Fellows who completed a recent reader survey.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.