One country’s tipping point in the journey towards a free and fair democracy.

In the weeks that followed the general election held on 19 May 2019, the atmosphere in Malawi was thick with unrest and anticipation. The outcome that had declared incumbent president Arthur Peter Mutharika the winner was heavily contested and triggered a series of events that saw a peak in Malawi’s fight for democracy.

The results of the elections were contested based on irregularities reported at polling stations (including the altering of result sheets with correction fluid), as well as several errors noted in the accounting and auditing of results submitted to the national tallying centre. This evidence, gathered from samples of results sheets from different polling stations, was enough to galvanise civil society groups to call for fresh elections and petition the resignation of the chairperson of the Malawi Electoral Commission (MEC), Jane Ansah.

When the Human Rights Defenders Coalition (HRDC) began coordinating nationwide protests to demand electoral justice, Malawians took to the streets in the hundreds of thousands in response. The cities of Lilongwe, Blantyre and Mzuzu seethed with activity as thousands joined the marches to serve government officials with petitions demanding justice. While the protests started out peacefully, clashes between protesters and the police soon saw city streets descend into chaos. Tear gas and live ammunition were used on the protesters, who retaliated by hurling stones and starting fires. For weeks, it became impossible to carry out business as usual in the major cities across the country as shops and institutions were shut down to avoid damage.

The refusal of Mutharika and Ansah to step down in the face of intense pressure from the ongoing mass demonstration led to a watershed moment: the opposition decided to join hands and take the case to the constitutional court. Led by Malawi Congress Party (MCP) president Lazarus Chakwera and United Transformation Movement (UTM) leader Saulos Chilima, the newly formed ‘Tonse Alliance’ argued that the irregularities were sufficient to overturn the results of the election.

Finally, it seemed, there was the necessary determination and resolve – at all levels of the Malawian populace – to ensure that justice would prevail.

A complicated history

Following the country’s independence from Britain in 1964, MCP, under the leadership of Dr Hastings Kamuzu Banda, established a one-party rule that saw the country devolve into a dictatorship that lasted three decades. The party employed authoritarian and intimidation tactics to suppress opposition, restrict basic freedoms and consolidate power. A 1997 article by Julius O Ihonvbere detailed how the absolute control and repressive tactics under Banda’s regime fostered “a climate of fear almost unparalleled anywhere in Africa, even in countries wracked by violence.”

It was only in the 1990s that widespread protests over the increasing economic crisis and international pressure condemning human rights violations pressured Banda to call a referendum, ushering in multi-party democracy. The first democratic elections were held in 1994 and the United Democratic Front (UDF) emerged victorious, with Bakili Muluzi becoming the first president under the new government and going on to serve for two terms.

While the next 15 years of relatively peaceful transfers of power in Malawi might appear, at first glance, to be a success, a closer look reveals a period of democracy riddled with challenges including in-fighting, nepotism and corruption, leading to protests and periodic unrest. Following the success of the student-led mass protests to overturn one-party rule (1992–93), Malawians once again took to the streets in 2002 to protest a proposed third term under Muluzi. Bingu wa Mutharika succeeded Muluzi as president in 2004 but, in 2011, during his second term, Malawians again turned out to protest poor economic management and governance by his administration; after Bingu’s sudden death in April 2012, his vice-president, Joyce Banda, was sworn into office to serve as the first female president of Malawi. In 2014, Bingu’s brother (and cabinet minister at the time), Arthur Peter Mutharika, was chosen to represent the DPP, following which he became the fifth president of Malawi and served a single term until the contested May 2019 elections.

The rampant corruption uncovered during Joyce Banda’s term (dubbed ‘Cashgate’), as well as the socioeconomic challenges that the country continued to face under Arthur Peter Mutharika, all contributed to growing frustrations among citizens which were channelled through ongoing protests led by civil society groups. Attempts to hold leaders in government to account rarely yielded results. There was little hope that the fight to overturn the May 2019 elections would turn out any differently, but protesters and the opposition, represented by the Tonse Alliance, refused to relent.

Democratic tipping point

The mass demonstrations following the May 2019 elections continued over a period of nine months, alongside the hearing of the election case by the constitutional court, which finally concluded in February 2020. Sensing that the country was at a tipping point, Malawians eagerly awaited the judgment that would determine whether the results of the election would be upheld. Citizens across the country and abroad followed the developments closely, staying updated through national news outlets on television, radio and social media.

Finally, in a historic ruling delivered on 3 February 2020, five judges of the constitutional court passed a judgment annulling the results of the May 2019 election. Delivered in an intense 10-hour hearing, the judges cited “widespread, systematic and grave” irregularities and misconduct in the MEC’s management of the elections and gave the commission 150 days to make the necessary reforms in preparation to hold fresh elections.

“Malawi’s success in establishing what many consider a peaceful democracy has been recognised globally”

With the world watching, Malawians returned to the polls on 23 June 2020, successfully ushering the Tonse Alliance into power. Lazarus Chakwera became Malawi’s sixth president and Saulos Chilima his vice-president. Supporters of the new government celebrated the result of their long, arduous months of protest, taking to the streets and social media to share in the victory.

What changed?

Several factors contributed to this significant evolution in Malawi’s democratic history. Chief among them was the freedom to organise and the efficiency of Malawi’s civil society in coordinating a response and calling for citizens to serve their complaints through official channels. As one of the organisations at the helm of these efforts, the HRDC was critical in ensuring local and international focus remained on the election case by drawing attention to the issues and seeking support from citizens across all levels of Malawian society to hold the government and judicial system accountable.

The HRDC, created in 2017 to provide protection and support for human rights defenders, consists of several organisations, including the Centre for Human Rights and Rehabilitation, the Centre for the Development of People, and the Malawi Law Society. To organise the May 2019 mass demonstrations, the HRDC used community mobilisation efforts to challenge the election results. A March 2021 report published by Solidarity Action Network detailed that the HRDC “stepped in to unite activists and citizens across the country, mobilising calls for greater accountability, and using litigation strategies to protect the freedom of assembly”.

Another critical factor that contributed to this historic victory for democracy was the transparency upheld by the judicial system, which demonstrated a commitment to constitutionalism and the rule of law. Malawi’s constitution protects fundamental human rights and enforces an independent judiciary system. This commitment to democratic justice was demonstrated not only by the judgment itself, but by the disclosure of high-level bribery attempts and threats to which the presiding judges were subjected during the trial. The level of scrutiny surrounding the election case inspired by the mass protests is thought to have contributed significantly towards a more transparent judicial process and, therefore, a successful outcome.

These factors working together meant that a strong legal case led by the opposition was supported by civil society efforts to hold key players in government and the judiciary system accountable. This collective effort, combined with the commitment to the rule of law upheld by the constitutional court judges, created an environment that enabled democratic justice to prevail.

Following the ruling in the election case, Malawi’s success in establishing what many consider a peaceful democracy has been recognised globally. In 2020, the five constitutional judges were awarded the Chatham House prize (an annual honour awarded to those who have made a “significant contribution to international relations”), in recognition of their “courage and independence in the defence of democracy.”

A vision for the future

While the overturning of the May 2019 elections was a key moment in Malawi and Africa’s political history that remains a resounding victory, the hope that was kindled in the public throughout the process has gradually dissipated. This follows increasing distrust in the new government for failing to honour campaign promises amid Malawi’s increasing economic challenges. The overburdened public health and education systems that are still recovering from the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic have been affected more recently by a cholera outbreak that the World Health Organization has declared the deadliest in the country’s history. Forex shortages, high (and rising) cost of living and inflation have led to growing frustration among Malawi’s citizens.

The fight against corruption continues, with attempts to undermine efforts by the Anti-Corruption Bureau (ACB) following a recent case suggesting widespread corruption involving high-level officials from different government departments. The civil society movement seems to have lost the momentum which fuelled the May 2019 protests, with some activists within the HRDC leadership being appointed into government positions by the Tonse Alliance.

Malawi’s journey towards democracy has not been without its challenges, but united fronts and perseverance have often paid off. Some of the achievements that the country continues to benefit from include: the electoral system reforms that have ensured a more inclusive democratic approach; the independence of political institutions such as the judiciary and ACB; and strong civic participation and engagement – including a growing number of youth and women-led organisations that continue to fight for human rights in the country. Through a commitment to constitutionalism, rule of law and civil society engagement, Malawi has demonstrated growing potential in democratic governance from which other countries can draw important lessons.

The fight for democracy, however, remains far from over. As we await the next presidential elections in 2025, the hope is that Malawi continues to learn from its past successes and remains vigilant in the face of democratic injustice.

Singalilwe Chilemba is a development professional, feminist storyteller, and the Founder of Utawaleza Malawi, a creative enterprise promoting literature, arts and culture in Malawi.

Artwork by Ellis Singano for the RSA. Ellis is a Malawian batik artist whose work has appeared in over 30 exhibitions.

This article first appeared in RSA Journal Issue 2 2023.

Read more Journal and Comment articles

-

Worlds apart

Comment

Frank Gaffikin

We are at an inflexion point as a species with an increasing need for collaborative responses to the global crises we face.

-

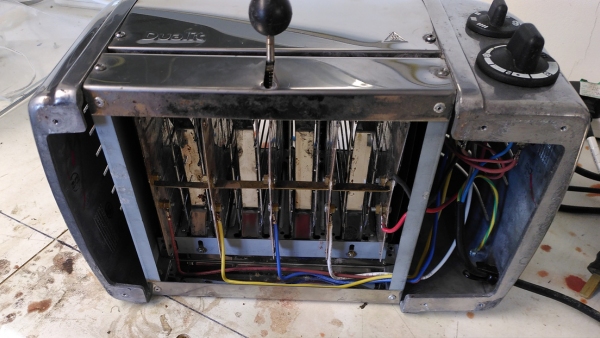

Why aren't consumer durables durable?

Comment

Moray MacPhail

A tale of two toasters demonstrates the trade-offs that need to be considered when we're thinking about the long-term costs of how and what we consume.

-

You talked, we listened

Comment

Mike Thatcher

The RSA responds to feedback on the Journal from over 2,000 Fellows who completed a recent reader survey.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.