How a ‘big myth’ sold the American people on the magic of the marketplace.

Ever since the rise to power of Ronald Reagan in the US and Margaret Thatcher in the UK, American and British public policies have been heavily influenced by a ‘big myth’. It is the idea that markets are not just economically efficient, but that they can be trusted to work wisely and well. In fact, so well that we don’t need government much at all. Governments just need to ‘get out of the way’ and let markets ‘do their magic’.

We call this view ‘market fundamentalism’, because it often takes on the quality of religious faith, as when the New York University professor Jonathan Haidt – a regular on the US talk show circuit and at the World Economic Forum at Davos – argues that it’s “not crazy to worship markets”, or the Chicago-school economist Deirdre McCloskey (only slightly tongue-in-cheek) crosses herself at the mention of Adam Smith. Margaret Atwood puts it this way in her book Payback: Debt and the Shadow Side of Wealth Management: at some point in the 20th century “people began substituting something called ‘the Market’ for God, attributing the same characteristics to it: all-knowingness, always-rightness, and the ability to make something called ‘corrections,’ which, like the divine punishment of old, had the effect of wiping out a great many people.” Smith’s ‘invisible hand’ was an obvious allusion to the hand of God.

Market-based economies have produced substantive wealth; they have also created devastating problems. From the “dark satanic mills” and monopolistic capitalism of the late 19th century, through the twin crises of crippling workplace injury and the Great Depression of the early 20th century, to our current breathtaking income inequality and dangerous climate disruption, market failures have been frequent and consequential. To the extent that these failures have been remedied, it has generally been not by markets correcting themselves, but by government action to constrain markets, redistribute wealth, or provide for human needs that markets neglect.

Why have so many people accepted a worldview that history has shown to be inadequate at best? One part of the answer involves a long history of propaganda – led by American business leaders – to persuade us of its truth. The story begins in the early 20th century, with a debate over electricity.

Electricity for all

The introduction of electricity in the early 20th century revolutionised transportation and recreation. Cities installed electric lights that made for safe walking at night; electric streetcars enabled the development of suburbs, amusement parks at the ends of their lines, and outings in the country. Electricity made Henry Ford’s assembly line possible, along with countless other industrial innovations. It also transformed the American home, replacing dirty and dangerous gas lamps and paving the way for electrical appliances that made household labour less arduous. By the early 1920s, most urban Americans had electricity in their homes. But rural America had been neglected.

Electricity generation in the US was mostly the work of entrepreneurs – famously Thomas Edison and George Westinghouse – and the private utilities that put their machinery to work, such as Edison Electric. The men and their companies were extraordinarily successful; Edison and Westinghouse became household names. But they had not found a way to bring electricity to rural customers at a profit. In 1925, General Electric put it this way: “the purchasing power of... 1.9 million [farmers] is too low to put them in the potential customer class.”

In many other countries, electricity was viewed not as a commodity to be bought and sold at a profit, but a public good that demanded governance to ensure equitable distribution. The contrast in results was stark: by the 1920s, nearly 70% of northern European farmers had electricity, but fewer than 10% of US farmers did. To add insult to injury, many private utilities were corrupt, overcharging customers and then cooking the books to make it seem it wasn’t so. In this context, leading Americans began to argue that government needed to get involved in electricity generation and distribution. In response, the National Electric Light Association (NELA) launched a massive campaign to persuade the American people that their needs could be best met if the government not only left electricity markets alone, but all markets. They would do this by insinuating their views into American education.

‘Expert’ influence

The NELA academic campaign had three major elements: first, they recruited experts to produce studies that ‘proved’ (contrary to what most independent observers had found) that private electricity was cheaper than public electricity. NELA found willing propagandists in faculties across the country. A professor at the University of Colorado was paid $1,692.33 – about a full year’s academic salary – for a survey of costs at municipally owned power plants in Colorado; not surprisingly, its conclusions were unfavourable to the municipal plants. At the University of Iowa, an electrical engineering professor was paid to prepare a series of reports favouring private electricity generation; NELA distributed the report “just as widely as we could legitimately”. It would be years before Americans learnt these studies had been commissioned by the electricity industry and that their authors had been told what they needed to say.

NELA executives then moved on to their second phase: rewriting American textbooks and, in effect, American history. They recruited and paid academics to rewrite textbooks to make them more enthusiastic about private electricity and enterprise capitalism, in general, and pressured publishers to modify or withdraw textbooks that NELA found objectionable.

Realising that pressuring academics and publishers might be considered inappropriate, NELA worked to gain cooperation from large publishers first, on the theory that once they were “straightened out and are working with us, the small publishers will naturally fall in line”. When a new text proved satisfactory, NELA or its members paid for copies to be widely distributed. In Missouri, for example, the St. Joseph Gas Company helped pay for copies of a new book to be sent to every high school principal in the state.

While NELA shills sang the praises of competitive markets, NELA’s short-term goal was to prevent competition from municipal utilities. The long-term goal was to foster not just a positive view of the American electricity industry, but a positive view of capitalism and a negative view of government engagement in economic affairs. In this context, NELA introduced two ideas that would prove crucial in nearly all later arguments about the virtues of free-market capitalism and the dangers of government action in the marketplace. The first was the allegation that government involvement in the marketplace was a departure from US history. The second was the claim that free-market capitalism was the embodiment of freedom, writ large, and that any restriction on the freedom of any business would put the American public on a slippery slope to tyranny. In later testimony to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), observers noted that the secretary of NELA’s Connecticut Committee on Public Service Information had admitted that industry statements were “intended [both] to discredit municipal ownership”, and to influence children (as future voters) to reject any thoughts sympathetic to state ownership and regulation.

The third component of the academic campaign was direct intervention in university programmes to develop pro-laissez faire, anti-regulatory curricula. Programmes of ‘reciprocal relations’ were established across the US, including at Washington State University, Penn State, Harvard, Northwestern, and Purdue; state agricultural colleges in Nebraska, Colorado and Missouri; and the Smithsonian Institution. The sums offered to support those relations were substantial: in 1925, Northwestern received $25,000; in 1928, Harvard received $30,000 – the equivalent of about $500,000 (£400,000) today. The goal was to support the development of courses and programmes in business and economics whose curricula were organised around principles of free enterprise and private property as the foundations for economic growth, prosperity and freedom. Influencing what was taught in colleges and universities would be the ultimate ‘win’ for NELA. As one executive put it,“The Colleges can say things that we cannot say and be believed.”

NELA’s... long-term goal was to foster not just a positive view of the American electricity industry, but a positive view of government engagement in economic affairs

The misinformation blueprint

On the surface, NELA lost its fight; it was discredited and disbanded. But it regrouped as the Edison Electric Institute, which exists today and remains a powerful political lobby. Despite New Deal rural electrification, the United States today still has a predominantly (about 90%) private electricity system that is less strongly regulated than in many other countries. On average, customers of publicly owned utilities pay about 10% less than customers of investor-owned utilities and receive more reliable service. When attempts were made in the 1990s to deregulate the system entirely, it was a disaster for consumers. The Enron company gamed the system before going bankrupt, and several of its executives went to jail for fraud, conspiracy and insider trading. Electricity deregulation also proved a disaster for the people of Texas: when the state’s power grid failed in the face of an extreme winter storm in 2021, it left more than 700 dead and somewhere between $80bn and $130bn (£64bn and £104bn) in damages.

The core arguments developed by NELA have also been used by other industry groups, most notably tobacco and fossil fuels. A BBC investigation recently showed how the American gas industry is once again claiming that government action to address a market failure – in this case the social cost of carbon – is a threat to personal freedom, an example of government ‘overreach’. And it’s not just the gas industry. “They’re not taking my gas stove,” declared West Virginia’s Democratic Senator Joe Manchin. Of course, no one is proposing to ‘take' anything away from anyone. The reality is that if we do not do something to stop the unfolding climate crisis, many of us are going to lose a lot more than a gas stove.

Seeing the light

Market failures are a feature, not a bug, of capitalism. To point that out is not to be a socialist, but a realist. The central failing of a good deal of current thinking – and not just market fundamentalism but also mainstream business thinking – is to brush this reality aside, and claim, for example, as The Wall Street Journal recently did, that the only way to address climate change (and by implication, other pressing challenges) is through “the mostly unregulated progress of markets and technology”. The time has come for a serious discussion of how to rethink and reform capitalism to deal seriously with the social and environmental costs of capitalism.

Naomi Oreskes is the Henry Charles Lea Professor of the History of Science at Harvard University, and a visiting scholar at the Berggruen Institute. She was awarded the RSA Silver Medal in 1981 for research performed as an undergraduate at Imperial College.

Erik M Conway is a historian of science and technology who works for the California Institute of Technology.

This article has been excerpted and adapted for the RSA from their new book, The Big Myth: How American Business Taught Us to Loathe Government and Love the Free Market.

This article appeared in RSA Journal Issue 2 2023.

Read more Journal and Comment articles

-

Worlds apart

Comment

Frank Gaffikin

We are at an inflexion point as a species with an increasing need for collaborative responses to the global crises we face.

-

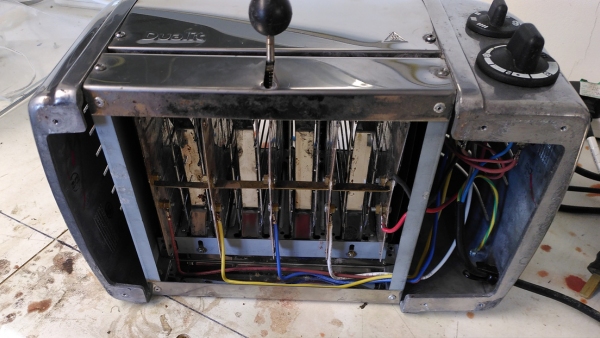

Why aren't consumer durables durable?

Comment

Moray MacPhail

A tale of two toasters demonstrates the trade-offs that need to be considered when we're thinking about the long-term costs of how and what we consume.

-

You talked, we listened

Comment

Mike Thatcher

The RSA responds to feedback on the Journal from over 2,000 Fellows who completed a recent reader survey.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.