The problematic state of plastic systems has received a great deal of attention in recent years. Their inexpensive nature and wide applicability have made the materials pervasive, but lacking systems to address and account for end-of-life has created a massive, steadily growing waste challenge that is highly diffuse in nature.

In recent years, the scientific community has worked to better understand the size and nature of the problem both globally and locally. This post is the first in a series that will look at the challenge through the lens of two studies recently undertaken in Bangkok, Thailand. One of those was led by the Stockholm Environment Institute Asia, and the other was carried out by the School of Global Studies at Thammasat University.

Before we dive into the Bangkok studies, it’s helpful to review a few studies that fostered awareness and understanding of the challenges we face. One, led by Roland Geyer, looked at global plastic production and estimated the annual totals from 1950-2015, as well as the fate of those materials. The other, led by Jenna Jambeck, looked at the amount of plastic waste produced in coastal countries and estimated the amount of those plastics entering the ocean by country. Together, they helped give a sense of the scale of the plastic problem, as well as places where we might focus. Along with awareness, these studies also fostered demand for systemic change. Several Southeast Asian countries were around the top of the list.

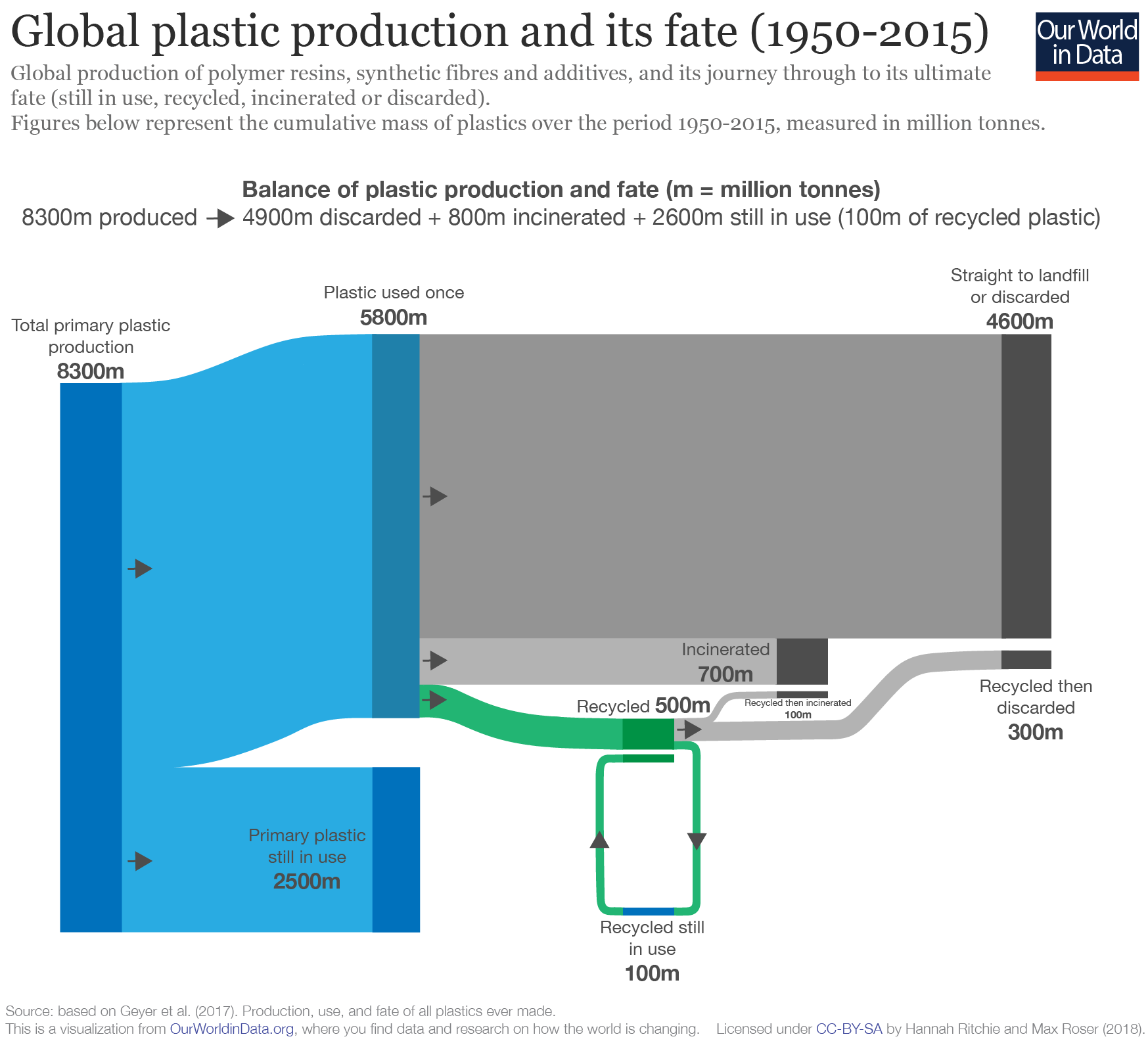

The Geyer study found that annual global plastic production grew prodigiously from a few million tonnes in 1950 to 379 million tonnes in 2015, a relative increase of nearly 19,000%. (The current figure is around 400 million tonnes, and that’s projected to double by 2050 if trends hold.) Meanwhile, the development of systems to handle the related waste lagged. Geyer’s team estimated that over those sixty-five years, 8.3 gigatonnes (Gt) of plastic were produced. For comparison, a gigatonne’s one billion metric tonnes is roughly equivalent to the weight of “10,000 fully-loaded U.S. aircraft carriers.”

While it’s estimated that 30% (2.5 Gt) of total production remains in use, roughly 70% (5.8 Gt) of it has entered one of three waste streams. The first of those streams included waste that was landfilled or discarded in nature. It accounted for nearly 80% of the 5.8 Gt of total plastic waste. The other two streams included 700 megatonnes (Mt) that were incinerated, and 500 Mt were recycled, but of the recycled materials, only 100 Mt were still in use. (A megatonne is one million metric tonnes.) 300 Mt of the recycled materials were eventually discarded or sent to landfill, and the remaining 100 Mt had been incinerated.

Prior to the study led by Jenna Jambeck, researchers aimed to measure the “standing stock” of ocean plastics. These were point-in-time estimates of the total amount of marine-based waste plastic. Jambeck’s team then added a view into the rate at which plastics were entering the ocean. Their study focused on 192 nations with coastlines and limited their data to plastic use within 50km of those coastlines due to the bulk of ocean plastics originating in those areas. Given those constraints, the team then calculated the low, mid, and high scenarios based on national figures for the percentage of plastic waste. They also calculated the percentage of mismanaged waste (waste that’s littered or dumped on open land). Their mid-range estimates for the included nations added up to eight million tonnes per year.

Prior to the study led by Jenna Jambeck, researchers aimed to measure the “standing stock” of ocean plastics. These were point-in-time estimates of the total amount of marine-based waste plastic. Jambeck’s team then added a view into the rate at which plastics were entering the ocean. Their study focused on 192 nations with coastlines and limited their data to plastic use within 50km of those coastlines due to the bulk of ocean plastics originating in those areas. Given those constraints, the team then calculated the low, mid, and high scenarios based on national figures for the percentage of plastic waste. They also calculated the percentage of mismanaged waste (waste that’s littered or dumped on open land). Their mid-range estimates for the included nations added up to eight million tonnes per year.

The Jambeck study also found that the size of a nation’s population and the quality of its waste management systems were the key factors determining where it ranked in the list of contributors to marine plastic waste. They also warned that without improvements to waste management infrastructure, the level of plastic waste that could enter the ocean might double their findings for 2010 by 2025.

As plastics have encircled the globe, they have also slowly broken down, leaving much of them in the form of microplastics. These small pieces of plastic—under 5 mm in length—have been found throughout our oceans and in the bodies of marine species across the food chain, as well as “from pole to pole and from the surface to the seafloor.”

While studies of microplastics are increasingly common, smaller particles known as nanoplastics—which are smaller than 1 micrometre—present a challenge for researchers. Due to their size, they require far greater investment to study, while they also present unique risks, like the potential to cross into cells or across the blood-brain barrier.

As the plastic waste problem grew, its scale and impact were somewhat obscured by China’s role in plastic value chains. Prior to January 2018, the nation was the largest importer of plastic waste. In recent years, mushrooming waste volumes overwhelmed the nation’s plastic waste processing capacity, thereby contributing to the nation’s environmental challenges.

In January 2018, China implemented new controls on the importation of plastic waste, which effectively ended the practice. Prior to the policy change, China and Hong Kong collectively took in nearly 1.9 million metric tonnes. Following the policy change, they received just over .2 million metric tonnes in the same period. The changes sent a shock through the global recycling system that fostered two important outcomes. First, all major exporters exported less plastic waste in 2018 than they did in 2017, thereby putting additional pressure on domestic recycling systems. And much of the remaining waste that could no longer go to China was shifted to Southeast Asia.

In Thailand, the plastic waste challenge has steadily grown for years. Prior to the pandemic, the nation long counted on tourism dollars to boost GDP, but accumulating plastic waste has increasingly threatened wildlife and degraded the natural beauty of the nation’s beaches, while its mounting presence created increased awareness of the need to tackle the problem. The onset of the pandemic pulled attention from the challenge, while it increased the use of plastic for things like PPE and takeaway food. Given that, the circumstances have likely compounded the problem while making it harder to study and otherwise interact with the systems that are in need of change.

But while the volume of waste is growing annually in Thailand, efforts are underway to improve waste management systems and their outcomes. The volume of source-separated waste increased 13% from 2017 to 2018 for a new total of 9.58 Mt (Pollution Control Department 2019: 36), so efforts to improve the system’s outcomes have shown progress.

This brings us two aforementioned Thai studies this post’s co-authors have been involved with. One was recently completed by a team led by Dr. Istvan Rado at Thammasat University’s School of Global Studies. The other, led by Dr. Diane Archer, Senior Research Fellow with Stockholm Environment Institute Asia, is slated to wrap up later this year. Both studies aim to provide a better understanding of the current state of local waste systems to support efforts to improve outcomes in those systems and their effects on communities in Thailand.

The Thammasat Study

Dr. Rado’s research was funded by the Thai government through the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT). The study focused on two neighboring communities in Thaklong municipality, which sits just north of Bangkok near the Thammasat University Rangsit campus where Dr. Rado teaches. The Thammasat team used a participatory approach to gain an understanding of the underlying forces driving plastic waste outcomes, as well as to look for possibilities for beneficial change.

The team conducted surveys with residents from just over 400 households in Krisana House (pop. 1,443) and Phoenix Park (pop. 1,100) to assess their waste management behavior and attitudes. Most respondents are long-term residents of the villages that work in nearby industrial plants. Aside from residents, in-depth stakeholder interviews included people involved with informal waste collection, as well as community leaders and relevant government agents. These perspectives provided insights into the functioning of the local waste management system, as well as gaps in existing 3R practices. Based on these findings, Thammasat University initiated a community-managed waste separation scheme in Krisana House in November 2020.

SEI’s Research

The study led by Dr. Archer is funded by a grant from Formas, the Swedish research council for sustainable development. It expanded on an earlier study conducted by SEIand UNESCAP, which opened a window into Thailand’s poorly understood informal waste sector. The current study looks to promote a circular economy by identifying opportunities to transition waste systems in ways that include the informal workers that are vital to the existing systems, while also fostering safer working conditions for those workers. The research is focused on gaining a better understanding of the regulatory, technical, economic, and physical environment, as well as behavioral elements related to household waste in urban Thailand. Plastic waste is a primary focus, and the effort will look for ways to reduce its generation and improve recycling rates. Along with practical changes available that are possible in the current circumstances, the team will work to identify policy options that could improve outcomes.

Dr. Archer’s team is working to reconceive the urban waste sector with the goal of integrating informal workers as partners. The big picture vision seeks “the achievement of just, inclusive cities alongside sustainable consumption practices.”

The study’s overarching question, “How can we ensure a sustainable transition for informal waste workers to become key waste management actors in a circular economy?” is supported by the following questions:

- How does urban household consumption and behavior influence patterns of solid waste generation?

- How do informal waste workers currently operate as collectors of recyclable household waste?

- What are the current barriers to a transition towards a more inclusive solid waste management sector in which informal waste workers are recognized and integrated as key waste actors in the sector?

- What policy, technical and behavioral changes are required to achieving the transition outlined above?

Next steps

Both studies will be wrapped up by the end of the year, and reports of findings are forthcoming. In this series of posts, we’ll work to share what we’ve learned along the way. This will include calling out possibilities for future research and opportunities to explore potential changes in the waste system.

For starters, we’re planning to share an overview of plastic value chains in Thailand that will provide an overview of things like the types and quantities of materials that are currently recycled and the process that’s undertaken. We’ll also highlight challenges in the current system, as well as some potential opportunities for further investigation. We’ll also look at the socioeconomic effects of the system on informal workers, as well as the impacts of the COVID pandemic on those informal waste workers.

We’ll start there and will also look at untapped possibilities for processing and manufacturing materials that are currently left as waste. We could also share our experiences collecting data for research in the pandemic, including the specific challenges we encountered and the modified approaches undertaken in the interest of helping others with adaptation.

The global plastic waste problem is massive, and it’s particularly challenging in Southeast Asia. We know these systems need to change. If we’re going to address it, we first need to better understand it.