What can fiction tell us about the future of work?

As we launch a collection of short stories on the future of work in an age of radical technologies, Asheem Singh reflects on how fiction can prepare us for the world of tomorrow.

The stories are curated by the RSA and the Orwell Foundation and are written by award-winning authors Darren McGarvey, Delia Jarrett-Macauley, Stephen Armstrong and Preti Taneja.

'The queue for heroin was as long as your arm, if your arm was the length of a small coastal town’ (Darren McGarvey)

This much we know: the world is an increasingly weird and uncertain place. Whether it is technological progress or political upheaval, Brexit or Boris: the only constant in our lives is change. For workers this is doubly the case. Gig work, automation, AI: all augur massive shifts. There seems to be little we can do but idly and unsatisfyingly speculate about the hurtling progress of terrifying technologies, byzantine economies, artificial intelligence, self-driving juggernauts, and robots that purport to do and act and think for us.

But there is an alternative view to fatalism like this. While we cannot predict the future (and never believe anyone who claims they can), we can prepare for it. While we cannot tell you what you will be doing or who you will be in fifteen years’ time, we can do our best to give workers the tools to face that which comes their way.

‘The locations are entirely random. The algorithm can’t get ahead of them. The killer has defeated the software.” (Stephen Armstrong)

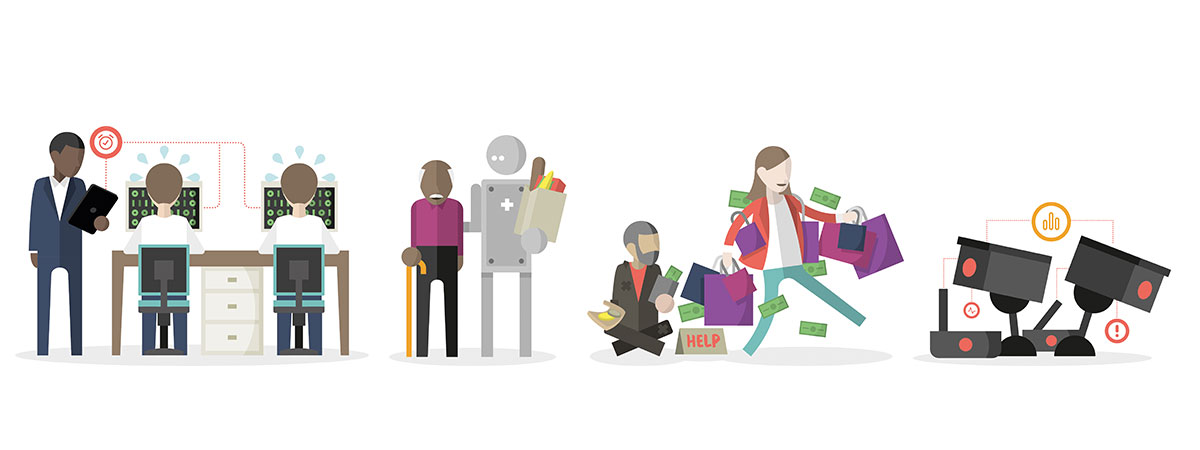

The RSA report, The Four Futures of Work, outlined four possible scenarios for the workers of 2035. There was a big-tech dominated scenario in which workers rights are fictive. There was a world of empathetic jobs and smiley services where menial tasks are performed almost exclusively by robot. There was a world with an increasingly precise culture of surveillance that is the logical conclusion of the neoliberal model. Finally, there was an exodus from the tech-maelstrom and a return to the land and the economies of communalism.

Already we are seeing research institutions, influencers and the media use the four futures. But it's not enough to shift those in the know. We need to work harder to shift that destiny; to strain and suffer and move it about; to agitate for a more socially just and egalitarian future for ourselves and our children. This is not just about changing minds and hearts; reforming not only institutions but cultures.

‘Every one of Tom’s friends had warned him about exposing his ideas to the health trust, and he had defied them.’ (Delia Jarrett-Macauley)

Language is the conveyance for all sort of passions and dispossessions: for the changing shape of love and labour in an age of radical technologies.

Science fiction writers and futurists through the ages have been part of this movement. Their work has been in turns satirical and prophetic. The dystopic grand guignol of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World sits alongside the technical excellence Arthur C Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. The idea of the dystopian counterfactual has form and it has function. Most recently, Charlie Brooker’s Black Mirror has elevated this artform to the status of cultural phenomenon.

Drawing on that great tradition, on the desire to map the contours of our changing world and its possibilities – but also the vampires and werewolves that lie in the shadows – we approached The Orwell Foundation with an idea about commissioning short stories inspired by the four futures. We weren’t sure what we’d get (we hoped it wasn’t Black Mirror lite). We weren't disappointed.

‘What is the most powerful way to capture an age? Take the tongue. Train it to word.. Saturate it into custom, layer by layer as blood seeps into earth.’ (Preti Taneja)

For 260 years the RSA has been best known for its social action and invention, for its championing of practical reason. In some ways these stories represent a departure; a venture beyond practical reason into the imagination.

These stories, written by award-winning authors Darren McGarvey, Delia Jarrett-Macauley, Stephen Armstrong and Preti Taneja present not statistics, nor prototypes, nor ideologies – but worlds. These worlds represent, in sum, not what we know but what we feel.

And in this age of uncertainty and anger, perhaps a bit of feeling is what we need.

pdf 1.4 MB

Related reports

-

Make it authentic: Teacher experiences of youth social action in primary schools

Nik Gunn Aidan Daly Mehak Tejani

Youth social action brings all sorts of benefits to young people and communities. But how do teachers experience it? And what can we learn from that experience?

-

Preventing school exclusions: collaborations for change report

Mehak Tejani Benny Souto Aidan Daly

School exclusion can change the course of a young person’s life. It can have long-term implications for their health, wellbeing, and future opportunities.

-

Digital innovations in lifelong learning: a global perspective

Veronica Mrvcic James Richardson Amy Gandon Aoife O'Doherty

Digital innovations in lifelong learning: a global perspective explores the drivers that support and the barriers that limit the international reach and impact of digital lifelong learning innovations.