Microbusinesses are booming in number, fuelled by a growing enthusiasm among people to strike out on their own. Yet mainstream pundits continue to belittle their contribution to the UK economy. Are they right?

Regular readers of this blog will know that the RSA has been working on a project called the Power of Small, which is exploring the causes and consequences of the UK’s growing microbusiness community. Last year we published a report looking at why so many people are starting up in business, and what this means for their livelihoods. Our message, and one we reiterated in a more recent paper, was that the vast majority of the self-employed enjoy working for themselves, and that this trend is a long-term one fuelled just as much by structural shifts as the recent economic downturn.

The next stage of our project will look at what the rise in microbusinesses means for the UK economy as a whole. Are these businesses sufficiently productive to contribute to UK economic growth? Do they have the capacity to innovate and develop more valuable products and services for consumers? Will they create employment opportunities for others? And are they in a position to contribute tax revenue to the exchequer’s coffers?

Funnily enough, just as I was thinking about these questions, I came across a very insightful piece by the blogger Steven Toft (aka Flip Chart Rick). The gist of his argument was that the rise in the number of microbusinesses spells bad news for the UK economy. In short, they suffer from low productivity, are not well managed, and are actually taking home a lower share of the UK’s overall turnover, despite growing in number. In a separate blog, Steven likens the scenario for small businesses to a nature documentary, where ‘more and more animals appear, desperate to drink from a shrinking water hole’.

Of course, Steven is not alone in this opinion. Speaking at our Self-employment Summit in February, Will Hutton described the growth in self-employment as “part of a picture of capitalism that is seriously dysfunctional,” while Vicky Pryce expressed concern that this phenomenon would “put us on a lower productivity path” for the foreseeable future. Academics have also expressed misgivings. A number of research papers and books, for example, have emerged arguing that our faith in small businesses is misplaced, with titles such as ‘The Illusion of Entrepreneurship’ and ‘The Small Firm Myth’.

But are these people right to be so sceptical about the merits of small businesses? Personally, I get their gripes that the media and politicians rarely acknowledge the downsides. Indeed, all you hear from public figures is praise and adulation for ‘entrepreneurship’. Still, based on everything I’ve read and all the people I’ve spoken to over the past couple of years, I can’t agree with the likes of Hutton, Toft and Pryce. Sure, the picture is not all rosy, but the one they paint is far too gloomy.

So, in a series of blog posts, I’ll be looking in more detail at how microbusinesses fare on the golden economic issues of today: productivity, innovation and employment.

Let’s start with productivity, which is roughly defined as the amount of labour it takes to create a given output, whether that is making a car, sewing a dress or diagnosing a patient. The higher productivity rises, the more output we produce and the more prosperous our society becomes (assuming a reasonable distribution of the proceeds). The problem is that the UK has performed relatively poorly on this major economic indicator, at least over the last decade or so. According to the Office for Budget Responsibility, productivity in the UK fell sharply during the recession and is currently still 3 per cent lower than in 2008.

Theories abound as to the causes of our productivity puzzle, but what binds most of them together is the belief that the answer to our productivity woes lies in large firms, not small ones. The reason is simple textbook economics: large firms are more productive because they can achieve economies of scale and allow workers to specialise in different roles – something Adam Smith recognised 240 years ago when he used the now famous example of the pin factory.

But does the theory bear out in reality? Apparently so, according to data amassed as part of the government’s Business Population Estimates (BPE). This shows that turnover per worker in very large firms (500 plus employees) is more than twice as great as in microbusinesses (0-9 employees).

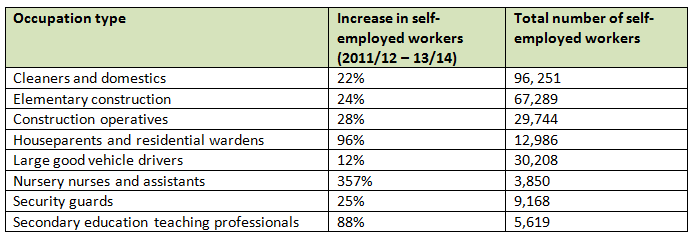

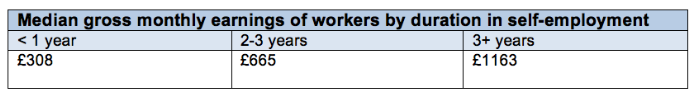

Look more closely, however, and several caveats come into view. The first point to note is that the high degree of churn in the small business community may distort our analysis. Many who move into self-employment will exit their business shortly after starting, with approximately a quarter dropping out within their first year and a half before their third anniversary. The effect of this ‘revolving door’ phenomenon is to bring down average productivity levels for microbusinesses, since there will always be a new cohort who are getting to grips with their market and turning over very little revenue. Were we to remove these fleeting firms from our analysis, the overall financial health of the small business population would look significantly better.

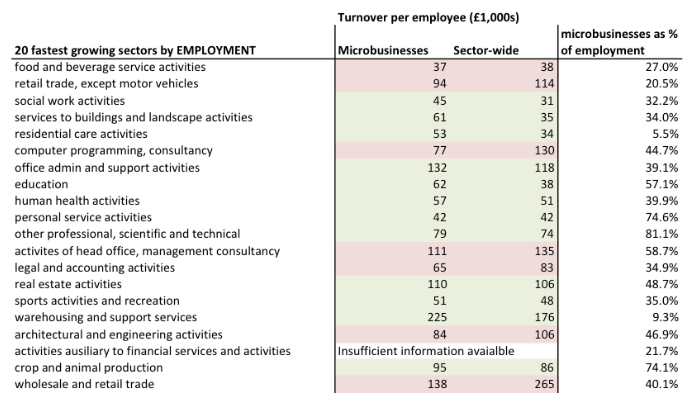

Indeed, we know from the Understanding Society Survey – which tracks the same respondents over time – that the earnings of the self-employed increase sharply with tenure. Those who have been self-employed for more than three years earn nearly four times as much as those who have been in business for less than a year (see below). Thus, the productivity of more seasoned microbusinesses is likely to be much higher and their overall economic impact more positive.

A second major caveat is that productivity among firms varies significantly by industry. Our analysis of the Business Population Estimates data shows that the average turnover per worker in microbusinesses looks far more favourable when we look at the fastest growing sectors of our economy. When we exclude sole traders from the microbusiness category (for the reasons of churn stated above), we find that microbusinesses have higher productivity levels in 12 of the 19 fastest growing sectors, as judged by employment growth between 2010 and 2014. This includes office administration, education, health and architecture/engineering. Looking at the data in this way, microbusinesses could be seen as fuelling economic growth rather than hindering it.

Finally, there is a geographical dynamic to contend with here. A growing body of evidence shows that small firms are more beneficial than large firms for the local economies in which they operate. This is in large part because their owners are more likely to live in the same area, thus keeping money flowing in the surrounding community. In contrast, large firms may extract money by sending profits to shareholders in other parts of the country – something the New Economics Foundation describes as ‘the leaky bucket’ phenomenon. According to the Federation of Small Businesses, every pound spent by a local authority with a local SME generates an additional 63p of benefit for the surrounding community, compared with the 40p generated by large local firms.

None of this is to dismiss the genuine concerns that some have with the microbusiness boom. Rather it is a reminder that we need more nuanced analysis on both sides of the debate. Only by getting into the finer details can we make a fair judgement as to whether a growing number of microbusinesses is good or bad for the UK economy as a whole, as well as for each and every one of us.

Keep your eyes peeled for the next blog on innovation.

Follow me on Twitter.

Related articles

-

The self-employed: rich, poor or something more?

Benedict Dellot

Barely a week goes by without another news story charting the fall of self-employed earnings. But how much do the headlines match reality?

-

5 tax reforms to create a more entrepreneurial society

Benedict Dellot

Small businesses don't want sweeping tax cuts and special favours. They want a tax system that is clear, fair and progressive. Here are 5 ideas to get us started.

-

Think blockchain is all about Bitcoin? Think again

Benedict Dellot

A new book by Don and Alex Tapscott argues that blockchain could help shake up the sharing economy, push out middlemen, and make micro-entrepreneurs out of all of us. Benedict Dellot explores.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

Is this part of TTIP and globalisation?

Small businesses are effective, but perhaps they are too shrewd for statistician and tax collectors. In my county 85% work for companies with fewer than four employees. They are more committed, and their efficiency may use different measures.

This country needs to concentrate upon local economies - that pathway makes more people content. The biggest weaknesses are created by our bankers. We need a network of small banks, such as Sparkasse in Germany, which cannot be gobbled up by large multinationals and who know their customers.

Big is not beautiful. Big allows 1% of yheworld to 'own' 50% of its wealth. It produces inequality.

You have to think about viable options for individuals - can their CV get them a job ? Is a zero hour contract with a large employer preferable to working for yourself? Why is a micro business an attractive option rather than returning to a corporate employer after a career break.

I once read that an inefficient economy, inefficient companies, create more jobs because of the simply need of more people to create and produce the goods.

If that's correct (maybe there is or will be an article about that), wouldn't it be better in terms of low unemployment rates? And how would the income develop in this scenario?