A couple of years ago, I was told of two young mothers who were studying for a qualification in nursing care. Towards the end of their studies a local Job Centre Plus insisted that they make themselves available for work or face sanction. They left their course and failed to qualify. They lost out and their time had been wasted. They were locked in the same oscillation between benefits and poor quality work. And society lost too - we need nursing care workers.

There seemed to be something so unjust in this story that it required further deep reflection. What sort of system could create this situation? The answer seemed to be one whose internal logic was arbitrary, coercive and short-sighted. The balance between the state and the individual was all wrong.

As the RSA pursues the ‘power to create’, this interface between the state and the individual needed further research and thought – especially as it was almost abusive in the case of the modern welfare state. That’s why we thought Basic Income might provide a better answer.

A Basic Income is an unconditional payment to each individual (ie it is not based on household). It is a building block for security and is designed to support the individual as they work, care (or are cared for), set up a business, or learn.

We have seen interest in the idea of a Basic Income swell over the past twelve months and as we developed our thinking, the work of the Citizen’s Income Trust (CIT) and others became crucial. CIT have spent the past three decades researching the proposition theoretically, practically, and fiscally. In the US, Switzerland, Netherlands, Finland and Canada there is an energetic debate about a Basic Income and pilots are being carried out. A system that has mainly been tried in the developing world is starting to gain real traction elsewhere including in the US state of Alaska. Basic Income-type experiments were first carried out in the US and Canada in the 1970s.

Increasing modern concerns about the impact of automation, artificial intelligence, and superlative computing power has also driven interest.

The RSA is becoming involved in the debate not simply to add to the considerable philosophical and theoretical thicket. We have accepted the arguments in favour – that Basic Income is the best system to support the range of contributions that people wish to make - as well as being the most humane system- and we set ourselves the goal of helping shift the idea more towards the mainstream and practical reality.

We accepted the 2012-13 modifications made by the Citizen’s Income Trust to a ‘pure Basic-Income’ model. Disability support and housing costs are not included in our scheme as they are not in CIT’s scheme. We do suggest, though, how housing benefit could be reformed to prevent means-testing combined with high withdrawal rates being reintroduced via the back door. These ideas range from low taper withdrawal to a new proposal for a Basic Rental Income. This would be a payment made on a local basis to all renters funded by a Land Value Tax. It’s an idea that we look forward to exploring further.

The major modifications we have made to the CIT model are three-fold: we have adopted a genuinely progressive tax system to make the tax simple and fair; we redistribute resources to families with young children to prevent losses in transitioning from Universal Credit; and we add some ‘design features’ to the model in order to emphasise that recipients, ie all of us, are expected to use this resource to make a contribution. Our model works as follows:

-

Payments are made to every citizen on a universal basis. EU nationals would receive them only after contributing to the system for a number of years in line with current EU law. Other international migrants would be subject to existing benefit rules. Prisoners would not receive it.

-

The weekly amount that any working age person receives is a ‘basic’ amount. In other words, if they are fit and able to work they would have a very strong incentive to do so. And they would not get trapped at low earning levels. This contrasts very heavily with the current system.

-

All recipients over 18 could be required to be on the electoral roll, thereby reinforcing citizenship.

-

A ‘contribution contract’ for those aged 18-25 could also be introduced. It is made with their friends, family and community to ensure they are contributing and these ‘contracts’ would be in return for the basic income. However, there should be no state monitoring of these contracts and sanctions will not be imposed if commitments are not kept to for any reason. This stops sanctions being re-introduced via another mechanism.

The Basic Income would be paid as follows (on the basis of 2012-13 prices):

-

Basic Income of £3,692 for all qualifying citizens between 25 and 65.

-

Pension of £7,420 for all qualifying citizens over 65.

-

A Basic Income for children aged 0-4 of £4,290 for the first child and £3,387 for other children aged 0-4

-

This is comparable to the benefits available to low-income households before the child begins school.

-

There would be a reduction in the Basic Income for a third child or more, potentially to zero. This would reduce the cost of the system and would align it even closer with prevailing political and moral expectations.

-

A Basic Income of £2,925 for those aged 5-24 years-old.

-

As a design option, the higher under-fives rate could be kept for older children too but at a cost of £3.7billion.

-

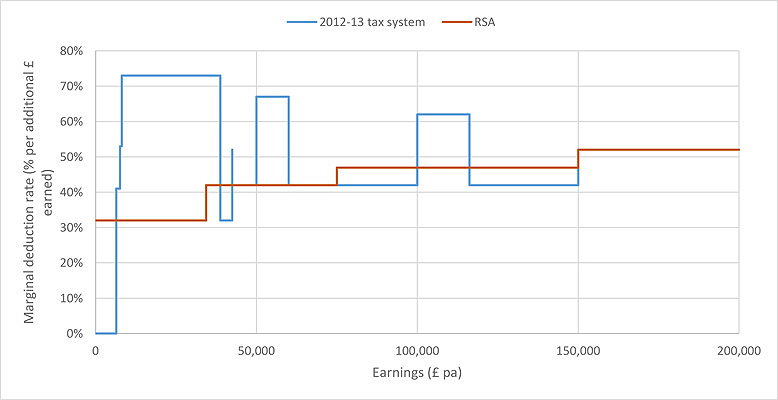

The tax system we outline would be shaped as follows (with the current system in blue for ease of comparison):

It is easy to see how our system achieves a much more sane, comprehensible and less distorting way of taxing and redistributing than the current ‘Himalayas’-style tax curve we can see above. The cost of our Basic Income system is greater than the current system or, indeed, the CIT alternative. We estimate that the changes we have made would cost up to 1 percent of GDP over and above the current model (including the abolition of personal allowances). This sounds like a considerable sum. However, it is no greater than the change that Gordon Brown made to tax credits and well below cumulative changes that George Osborne has made to personal allowances, VAT, inheritance tax and corporation tax despite austerity. If the benefits of Basic Income come to be accepted as did major changes to the pension system or NHS funding then 1 percent of GDP is more than affordable – especially in the context of a state that is forecast to be only 36 percent of GDP by 2020.

So who are the losers? Well, obviously, there are some losses for individuals earning over £75,000 compared with the current system. There are some losses for those who are locked for prolonged periods of time on very low hours. Serious thought is needed on how to address these individuals. Work conditionality and sanctions are not the solution - they are not working. Different types of support are needed and that applies just as much to the current system as it would do under Basic Income. However, the system is dynamic and people languishing in this way involuntarily is not as common as may first appear (people in this range tend to be on flexible and unpredictable hours/work and so their circumstances continually change up and down).

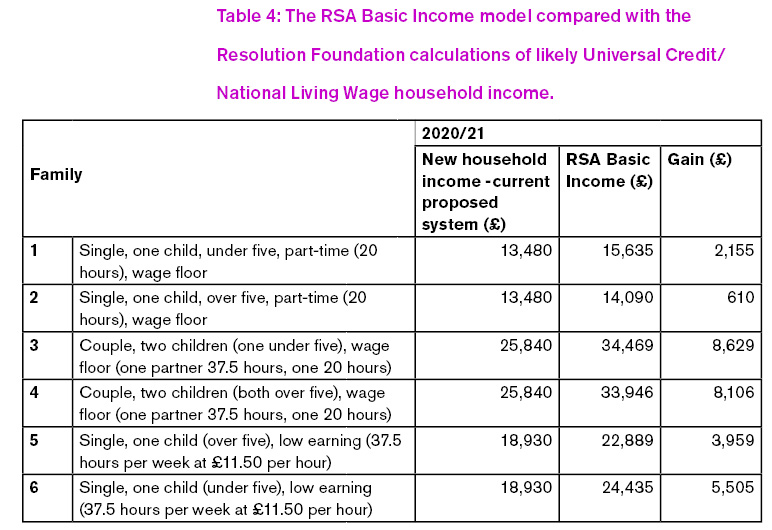

But the big game-changer that has yet to be seriously discussed is the introduction of Universal Credit and the ‘National Living Wage’. This changes the picture for a Basic Income system considerably. The National Living Wage means that incomes accelerate quickly beyond the point where there may be losses in a Basic Income system. This was a surprise to us but it needs further serious discussion as it quickly improves wage income to a level where there are net gains over the current system. We mapped the consequences of a National Living Wage combined with a Basic Income against the likely net income of five family types from 2020-21. The results were as follows:

This is an exercise we undertook before and after factoring in National Living Wage. That is the game-changer in all this. The large gains for families with two earners does raise the question of whether there is scope to make up some of the funding shortfall by looking at a higher tax rate at a slightly earlier level. Overall though, our redistributive adjustments mixed with the National Living Wage make Basic Income far more attractive as a relative proposition.

So that’s the technical bits out of the way. Why do this?

It’s quite simple: Basic Income supports people in nurturing their lives and frees them to create a new future. Those two young mothers who were taken off their nursing care courses are a case in point. Had there not been such an intrusion into their power to choose they would have got their qualifications and have a different life and be making a bigger contribution. With their new-found confidence they may even have got a degree by now or started a business. Does that matter? Their knowledge and experience about caring could be shared with others – not only on a professional but on a voluntary basis too. Their family life could have felt like it was on an even greater upwards trajectory instead of being locked between low quality work and an intrusive welfare state. Their mental health, educational outcomes, life satisfaction, all-round well-being could be much enhanced.

That’s why. This is not simply a theoretical exercise. It’s about what should constitute social justice in a society such as ours. So how about we push for a trial of the Basic Income at a city-wide level? Don’t take our word for it. Let’s try it in practice. Who’s ready to join the cause?

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

I am not a supporter of an unconditional basic income scheme (UBI) as conceived either by the Citizen's Income Trust or the RSA, but it strikes me that a UBI scheme in a country with a population the size of the UK cannot be economically feasible- without at some stage running into significant deficit funding or deferring a tax bombshell for future generations- if it fails to address the substantial and growing wealth gap between richest and poorest. Despite increasing efforts by HMRC to crack down on tax evasion and aggressive tax avoidance by the richest, the fact of the matter is that corporate wealth and the richest individuals in the main pay nowhere near their fair share of tax.

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/britains-divided-decade-the-rich-are-64-richer-than-before-the-recession-while-the-poor-are-57-10097038.html

Without addressing this serious anomaly, the burden of paying for a UBI will fall disproportionately on medium and low earners in full time work through elimination of tax allowances and the prospect of tax rises (which you have not specifically ruled out). Your report's reference to abolishing tax relief on pensions for the richest would barely cover a fraction of the cost. The main net gainers will be those who pay no tax at all- (eg. benefit recipients and those in work but whose earnings are too low to pay tax or face the very lowest rungs of tax).

Switzerland, a couple of years ago, had a referendum to put in place a maximum earnings ratio between the highest and lowest paid. The referendum was lost but I would argue that the reduction of the wealth gap and the consequent increase in revenue would substantially increase the prospects of success for sustaining a raised basic income for the poorest. Will the RSA support a maximum earnings ratio initiative for the UK to accompany its unconditional basic income? Such an initiative is no more 'political' than that of an unconditional basic income.

The main reason I have for not supporting the CIT/RSA UBI relates to the 'unconditional' doling out of money proposed- (an unenforceable 'contract' for recipents is not worth the effort of drafting on paper). In the wake of the collapse of the unpopular Brownite wefare state, a national consensus will never form supporting a large scale doling out of money to people with nothing expected in return. The RSA claims that its UBI will promote a socially responsible 'creativity' and strengthen a 'contributory' culture to society. I would like to see irrefutable hard evidence for this which goes beyond just one or two anecdotes.

The RSA report is also lacking in detail on;

a) whether the UBI will be means tested (or taken into account and deducted from the benefit of those whose benefit entitlement is income related). If this is not the case, and the benefit recipient wins a 100 per cent net gain, the national benefits bill will balloon again;

and;

b) what happens if the UBI does not cover the full living expenses of those on benefits. In this context, will means tested benefit top ups have to continue which, in the case of a job seeker benefit entitlement, will be conditional, have certain sanctions attached and entail bureaucratic intervention in individuals' lives.

Good stuff, Anthony.

I'm approaching this subject from the perspective of my research into a directly connected, networked society; human and resource resilience, and the scope for community-based legal agreements and instruments, for which the current government is leaving a vacuum.

My proposal is as follows.

Firstly, implement a Land (Location) Use Levy in £ or in £'s worth (more anon).

Secondly, pay a 'Land Dividend' directly (not touching government at all, with a service fee to a managing partner) and equally to all qualifying land occupiers.

The innovation is that this Land Dividend would not be paid in conventional £ created by the Treasury/Banks but in £1.00 Land Use Credits returnable in payment for the Levy.

Owner/Occupiers would be able to pay some or all of their own levy from their Land Dividend, while renters would be able to pay their rent with it since landlords will use the credits to pay their own obligation.

The outcome is a net transfer from those with above average exclusive rights over land to those with below average use.

The policies made possible by the above infrastructure are interesting.

Firstly, we now have a new (in fact ancient) means of investment in land through the simple expedient of land loans - ie selling £1.00 levy credits at a discount.

A £1.00 levy credit sold for 80p to an investor gives a 25% profit when it is returned in payment for the levy, and the phrase 'rate of return' actually derives historically from and describes the rate over time at which such credit instruments may be returned to the issuer. So if returned in one year the rate of return is 25% per annum; over two years 12.5% pa; over 5 years 5% pa and so on. Simply divide the profit by the period of return.

The outcome is a form of investment and funding which includes no compound interest (money for the use of money) since the return is in the value of land use over time.

This funding (which predates by millennia modern equity, debt and derivatives) enables a new - and optimal - form of equity release, of particular relevance to the ageing (asset rich) baby boom generation who are long of land but short of care for themselves and their property.

This brings me to the other side of the exchange, which is the younger generations who are long of care but short of property. Here there is the possibility of paying the land use levy not in £ but in care for people, or for property. (Farmers could pay their obligation in kind through a tithe).

In essence the outcome is a form of currency/credit which is local by definition, and the ability to mobilise underused resources - whether people or property - in a simple, radical but equitable way.

This holistic presentation at a Summer School in Volos, Greece might be of interest.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zl8_tCa7AtA

These complementary solutions are implementable bottom up, with no change in the law, and I have been working in Scotland and elsewhere on proofs of concept for some time.

If the NHS could be brought into being in only 3 years after the devastation of WW2, BI is certainly doable given political will. Not only would it liberate the people to get on with their lives, it would enable all forms of small business to evolve, support creative industries like arts, science and people coding in their back rooms. In short it would return the country to be the happier place that it once was before the onslaught of greed and beggar my neighbour occurred in the 1980s. It would also promote taking British citizenship among non-EU migrants and, along with the requirement to register to vote, flush out some of the black economy into the tax-paying world. Qualifying students would receive basic income which is also to be welcomed.

However there are a few caveats and gotchas I think in the RSA proposal, close though it is to my own ideas, which I don't think were discussed in the podcast nor here.

1) Permanent residence. An individual, or their qualifying parent, must have been resident for a period of perhaps 2 years, which would automatically mean that EU residents would be treated in the same way. It would also end the present farce of the PM going round the EU trying to alter fundamental features of the EU, an entirely unnecessary embarrassment to us all. But to receive BI, not only should a person be on the electoral roll (or their parent etc if a dependent), but they must also have declared the UK as their permanent residence and that they are claiming BI only from the UK. This will stop allegations of (and possibly actual) people also claiming elsewhere, or sending their children back 'home' while claiming UKBI.

2) Children. The definition of a 'first child' is becoming increasingly difficult where family structures are changing, families separate, second families appear etc. The current Child Benefit is higher for the first child, and will disappear for third and subsequent children born after April 2017. The rates you suggest are essentially the present CB rates which continue until a child is 16 or 18 years old. I would favour a child BI based purely on the child's age, higher perhaps in years 1-4 and reducing to reflect parental earning capacity or additional children coming along but possibly increasing at 18 when the child become an adult rather than 25, which seems very late to me as some people start their families well before that age.

3) Pensions. Pensions could be an additional top-up above the adult BI but to get the new flat rate state pension, you have to have worked for 35 years (up from 30). This is particularly disadvantageous to women who have taken maternity breaks so I believe the denominator should be reverted to 30 and the Senior BI should be 3692+min(n,30)*(7420-3692)/30 for n years worked.

4) NI. The opportunity should be taken to integrate these two - simply by abolishing NI and increasing the basic tax rate, perhaps to 30% or whatever is needed to raise the same revenue. Some transitional arrangements may be needed but the farce of increasing personal allowances has not been applied to NI, which is a non-cumulative tax and therefore hits irregular earners disproportionately.

5) Other support. It is inevitable that some housing and disability support will be required in addition but we need to ensure that the withdrawal rate is not onerous to avoid another poverty trap. I would suggest therefore a low starter income rate of 10% on the first (say) £5k of income. This may not avoid problems altogether but it would cushion the blow considerably. It would also mean that unqualified people (immigrants mainly) who would be taxed under the same system would be paying rather more (by their missing BI) than at present and be seen to be contributing up front, meeting some objections.

6) Wages. The move to a National Living Wage is of course the sudden realisation by the Chancellor that poverty wages have required (expensive) tax credits and since the financial crash, recovery (if that is the right word) has been with inappropriate employment, zero hour contracts and insecurity along the lines of 1930s piece-work. It sounds good but of course most people have costs that are weekly, monthly or annual so hourly rates are often of only marginal use. The NLW (or the Minimum Wage) hourly rate does very little to help anyone on substantially less than 40 hours a week.

Anyway enough of my 0.02p. Thank you for a well considered proposal. Now to get the politicians behind it but to do so in the present climate the rates must be adjusted a little to be revenue neutral or better. That's the reality I'm afraid! We can then see the benefit of basic income and adjust rates upwards as tax revenue improves.

Thank you John. Lots of key questions here - many are in my mind. I especially agree with regards pensions - which will become a basic income. We will need to explore further the feasibility (including politically) of a non-revenue neutral scheme. I will be blogging on this further soon.

Anthony