In autumn of 2015, Transport for London (TfL) finally acknowledged the arrival of Uber, the ridesharing platform hailing from Silicon Valley. Although Uber has been in London since 2012, TfL’s first attempts at regulating the company were made in the past year. While other capitals such as Paris and Amsterdam have tried to choke the company’s operations through court orders, London has given Uber a free ride when it comes to regulation. However, mounting pressure from Uber’s incumbents has forced TfL to act in recent months.

TfL drafted a suite of proposals to regulate vehicles for private hire based on an initial consultation that elicited nearly 4,000 responses. Among these proposals, Uber objected most to the following:

- A minimum five-minute waiting time between booking and beginning a ride

- A ban on showing vehicles available for hire (ie live tracking in an app)

- A restriction on drivers’ ability to work for more than one operator at a time

The rationale for these proposals was not clearly communicated, enabling Uber to counter that the plans made “no sense” and failed to consider that it would mean an end to a service users knew and loved. On this basis, the company launched its own campaign to rally its users in support of the platform.

Within the span of 24 hours, Uber’s petition against TfL’s proposals attracted over 100,000 signatures. It is no easy feat reaching that level of support and in such a short space of time. To put this into perspective, a black cab driver in London started a petition to ban Uber two years ago, but as of writing the number of signatures is hovering around the mark of 15,000.

For Uber, the key to keeping TfL at bay has been in successfully mobilising the masses in its favour. When TfL announced yesterday that it would be scrapping its proposals (following a second consultation that garnered four times the number of responses as the first), no one should have been surprised. At the core of Uber’s survival strategy is the crowd – its users, which include some drivers, but mainly passengers that are a fan of the platform’s relatively low costs and convenience.

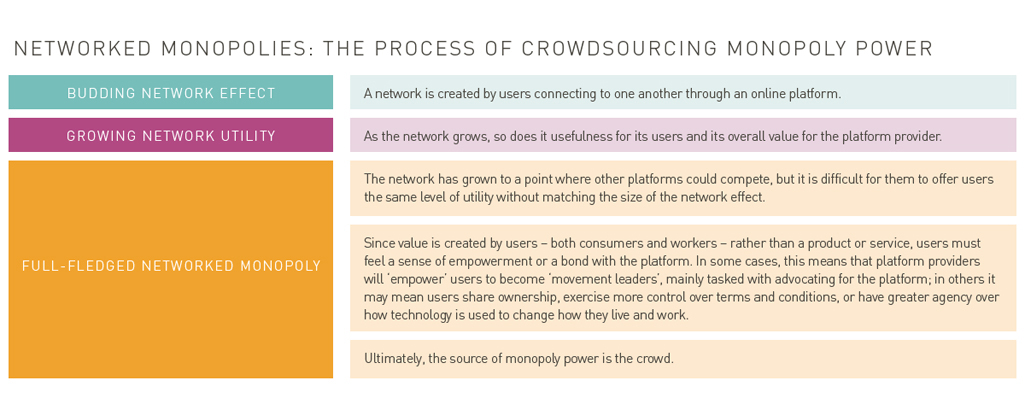

The RSA’s new report on the sharing economy details this strategy, which we refer to as the process of ‘crowdsourcing monopoly power’. Sharing platforms, such as Uber, are able to scale quickly because of the network effect, but can only maintain their considerable position in the market (especially while fighting regulatory battles) through transforming their user base into a movement of allies.

Another big player in the sharing economy that has similarly trounced recent attempts at its regulation is Airbnb. In San Francisco, the homesharing platform converted its hosts into advocates for the company using the same tactics as the organisers of Obama’s presidential campaign in 2008. These hosts helped Airbnb defeat Proposition F, a ballot measure aimed at restricting short-term rentals in the city.

There is a crucial difference of strategy between these platforms. While Airbnb is marshalling its hosts (essentially, the sellers or workers in this situation), Uber is uniting its passengers (the buyers, or consumers). Uber’s sellers are its drivers, some of whom are disgruntled with the platform because it does not guarantee security or offer employee benefits such as retirement coverage or accident and sick pay. As some of these drivers are protesting against Uber in our capital as well as in the US, it is simpler for Uber to rely on its consumer base for support.

As Uber masters movement building as a tool for resisting regulation, TfL should look to Uber’s drivers for a steer on what sort of regulation might be needed rather than to London’s cabbies or to consumers. The principle concerns here do not relate to safety and security (considering the capacity of sharing platforms to self-regulate in this regard), but rather to a new sort of monopoly power and what that means for all of us, but especially for workers using these platforms. Government must urgently rethink its approach to regulation or Uber (and other sharing platforms like it) will easily continue to grow its market to a point where it will be too late to intervene in a meaningful way.

Read our report "Fair Share: Reclaiming power in the sharing economy"

Related articles

-

How do we collaboratively regulate the sharing economy?

Brhmie Balaram

The Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) Select Committee published a report today on the UK’s digital economy, which the RSA provided evidence for earlier this year.

-

Banning Airbnb and Uber isn't sustainable in a global sharing economy

Brhmie Balaram

Brhmie Balaram offers a breakdown of why banning Airbnb and Uber isn't a viable long-term solution in a global sharing economy.

-

Blog: Top 5 takeaways for Government on the Sharing Economy

Brhmie Balaram

The RSA was asked to present evidence to the BIS Select Committee last week as part of the government’s inquiry into the digital economy. Brhmie Balaram gives her top five takeaways.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.