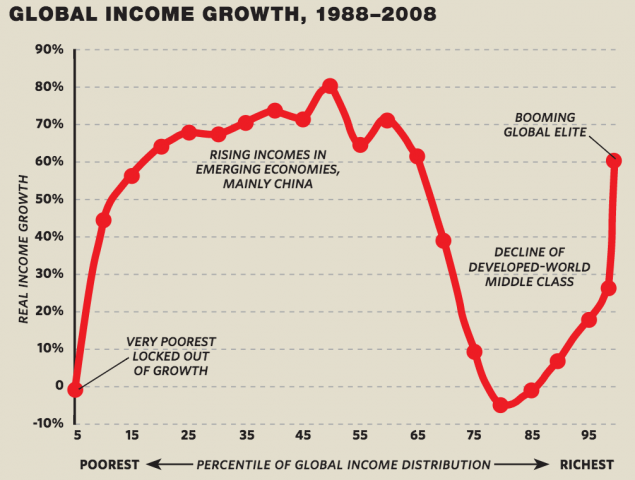

Trump’s victory has been portrayed as the biggest political surprise in modern electoral history. Yet as Branko Milanovic’s ‘elephant curve’ shows, political disenchantment rooted into stagnating incomes, globalisation and technological change has been long in the making. We just weren’t paying attention.

How did Donald Trump come to win the US Presidential election?

The Democrats undoubtedly could have fielded a stronger candidate. But this election was more than a character contest. Trump won because of hard economic realities and an abiding sense among the American working class that the system is no longer in their favour. Among white voters without a college education, Trump beat Clinton by 39 percentage points. The so-called ‘blue wall’ of blue collar Rustbelt states crumbled as Trump took Wisconsin, Pennsylvania and Michigan.

We should be wary of ascribing these results to widespread enthusiasm for Trump. Yes, he won the election but he did so with a lower voter turnout than in 2012 and a lower share of the popular vote than Clinton. More people turned out to vote for Mitt Romney than did for Trump. He is scraping into the White House with the backing of little more than a quarter of eligible voters, as millions others stayed at home.

Such political disenchantment is not borne of recent events. It cannot be explained by the economic downturn of 2008 alone, for all it meant in job losses, rising household debt and public sector austerity. Rather, it is disillusionment rooted in at least two decades worth of economic malaise that has beset low-income and low-skilled workers – a phenomenon present in many Western countries but one acutely felt in the US.

This is neatly portrayed in the economist Branko Milanovic’s ‘elephant curve’, a graph that plots changes in earnings among different income groups around the world since the late 1980s. Looking at the chart, one can see three obvious patterns. The first is that the income of the world’s richest citizens has grown dramatically – by around 60% for the very top percentiles. The second is that the world’s poorest – predominantly in developing countries – have experienced an equally healthy increase in their fortunes.

But the most striking revelation is the comparatively lacklustre income growth among middle-high earners, those who are effectively the low earners in developed countries. The Resolution Foundation’s Adam Corlett cautions against reading too much into these figures given the large variations in income growth between and within countries. But even when the countries are separated out, the pattern still holds for the US – possibly being even more extreme.

Corlett’s analysis shows that average income in the US grew by 2 percent per year between 1988 and 2008, but most of this was accounted for by big increases in the incomes of the already affluent. People in the bottom six deciles saw their pay packets grow by just 20-30 percent over the last three decades, less than half the 68 percent rise enjoyed by the top decile. When blue collar workers see a gilded few get materially and visibly richer, the seeds of discontent are inevitably sown.

This is not just about the rich soaring away (the tip of the trunk), it is also about poor countries catching up (the bulk of the elephant). Since the late 80s the world’s economy has become ever more open, with trade deals that have reduced tariffs, harmonised regulations and supercharged developing economies. China took on the mantel of workshop of the world, but it did so at the expense of US manufacturing, which today employs less than two thirds of the people it did in 1990. Offshoring was deeply disruptive to the automobile, clothing and steel industries.

The decline of US manufacturing has been particularly painful because few other sectors bestow so much meaning, identity and pride in their workforce. It was not only Detroit’s economy that was built on car manufacturing, it was also its culture, heritage and sense of self-worth. Working class communities in the US are being forced to seek out new identities, yet have been left wanting in the face of service sector jobs that lack obvious purpose or fulfilment. Little wonder Trump made the reshoring of US industry one of his defining campaign pledges.

Globalisation is not the only driving force behind the elephant curve. Technology has played an equally important role in loading pressures onto low-skilled workers. For all of today’s hype surrounding new forms of AI and robotics, technology has been automating jobs and tasks for decades. Bank tellers fell victim to ATM machines, secretaries to time-saving computers, and factory workers to automated picking and packing machines.

In a fascinating analysis of the US election results, the FiveThirtyEight writer Jed Kolko found a strong correlation between the likelihood of a county voting for Trump and the proportion of its jobs that are routine – such as those in manufacturing, sales, and clerical work. Where more than 50 percent of the jobs are routine, Trump averaged close to a 35 percent vote margin. In contrast, where less than 40 percent of the jobs are routine, Clinton scooped a vote margin of just over 30 percent. This is about status anxiety as much as economic anxiety as the nature of the job shifts.

So what to do about the elephant? The temptation is to see globalisation and technological change as inherently problematic – two forces that must be halted in their tracks before they do further harm. Trump has already mooted his ambition to renegotiate the terms of Nafta, and it is likely that the controversial TTIPP and TPP trade deals will be mothballed. Whether or not his infamous wall is built on the US-Mexico border, we can expect a tighter immigration policy and restrictions on the movement of labour.

Yet few answers can be found in the dark corners of isolationism or techno-pessimism. Global trade has brought unprecedented wealth to the world and lifted millions out of poverty. The US-China trading relationship can at times be sour, but the States is a huge exporter and beneficiary of trade deals in aggregate. Likewise, for all of the disruption it causes to particular sectors and occupations, technological change has been and will continue to be a major source of productivity gains – gains that make us more prosperous.

The problem is not with these wealth-creating forces per se but rather with the way in which the proceeds are distributed. Governments and nation states have it within their gift to create a tax, education and welfare system that opens up opportunity and allows people to live larger lives. But too often the policies fail us. Our welfare programmes are punitive and threadbare, our taxes reward rent-seekers over risk-takers, and we squeeze one generation to provide for another – all with little thought of the consequences.

It doesn’t have to be this way, of course. The RSA has championed the notion of a universal basic income that would bring dignity and economic security to all citizens, and we are in the midst of exploring the ideas of community wealth funds, new forms of co-operatives and mutuals, lifelong learning programmes, and employee ownership schemes. Social innovations like these are nothing new but they have never been more relevant or urgent. And as diverse as they are, they all have one thing in common: they enhance economic security and give people a meaningful stake in society.

The task before us – of achieving radical innovation at a time of nationalist populism – is mammoth and unrelenting. But if there’s one thing the events of 2016 have told us, it’s that anything is possible.

Related articles

-

Pensions coverage for the self-employed is pitiful – but it’s never too late to start nudging

Benedict Dellot

Pension coverage for the self-employed is pitiful, with just a fifth signed up to a private scheme. Could nudging be part of the answer?

-

The self-employed: rich, poor or something more?

Benedict Dellot

Barely a week goes by without another news story charting the fall of self-employed earnings. But how much do the headlines match reality?

-

5 tax reforms to create a more entrepreneurial society

Benedict Dellot

Small businesses don't want sweeping tax cuts and special favours. They want a tax system that is clear, fair and progressive. Here are 5 ideas to get us started.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

Back in May 1973, Professor Peter F Drucker wrote an article inthe Wall Street Journal the title of which was "Is Executive Pay Excessive". In the article he calls for an after tax wage differential of around 8 to 1. That high rates of differential were "socially divisive". I agree. In my book, I have caleed for a before tax wage differential of 20 to 1.

Regarding the topic of a universal basic income, I think that should be a "Parenting Skills Allowance" of 100 hours x NMW or where appropriate a "Carer's Allownce" at the same rate. JSA should be replace by a "Personal Development and Community Involvement Allowance of 15 hours (5 x 3 hour days) paid in the same way as the old EMA was distributed.

What is Univeral about people is that we all have parents; and some of us are parents. To qualify for the Parenting Skills and/or the Carer's Allowance the person must acuire an NVQ certificate in the appropriate category. A "super nanny" or a qualified carer within every family. A qualified child carer in every family would vastly increase the supply of child carers in "the market".

The amount paid would virtually wipe out the Housing Benefit cost, possibly 100% of the cost.