The word ‘regeneration’ increasingly causes eyes to roll and eyebrows to raise, and those proposing new development have often shifted to focusing on ‘place-making’. Local authorities talk about their role as ‘place-shaping’. Why should the word we use, to describe a programme which can stretch decades, matter? What is lost (and gained) by ditching regeneration and adopting ‘place’?

Regeneration has become a difficult word. I find that lots of professional colleagues are increasingly choosing not to use it. It is controversial. Every day I cycle past Elephant Park, a massive development site that used to be known as the Heygate Estate regeneration. Many displaced residents locally feel dissatisfied with how the benefits of huge corporate investment will ultimately benefit them. On the other side of London, the political challenge to Haringey’s Development Vehicle is rippling across councils.

It is a bit surprising that the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government use the term regeneration. The Mayor of London uses it too. Interestingly, for both, it is in the context of housing estates.

Of course, good projects ‘deliver’ things that are widely welcomed: improved homes, new homes, quality facilities and open spaces, new social and economic opportunities for citizens, and better services to support well-being and address social needs. Why should the word we use, to describe programmes which can stretch decades, matter? What is lost (and gained) by ditching regeneration in favour of adopting ‘place’?

All of us involved in ‘regeneration’ have seen projects and programmes which have changed the physical environment while the social and economic challenges remain – either located in new buildings or displaced elsewhere. The notion of ‘placemaking’ is, in my mind, a concession to this shortcoming. It is a retreat from the aspirations for social and economic regeneration.

There are successes to point to in regenerating the scale and quality of opportunities for residents in existing communities. Many of us continue to pursue that goal under the ‘estate regeneration’ banner, recognising that a masterplan alone is insufficient.

Having worked with Rochdale Boroughwide Housing (RBH) since the end of 2016 in the Lower Falinge and College Bank neighbourhoods, I’ve been impressed by their dual focus on ‘people and place’. They have made this explicit in their communications to residents and others.

These two adjacent neighbourhoods sit right next to Rochdale town centre, and, if it wasn’t for a dual carriageway, they’d probably feel like part of the town centre. A physical regeneration masterplan is being finalised, addressing public realm issues as well as replacing blocks of flats.

Our role has been to help RBH make plans for what should change for existing local residents in the future. A steering group includes several areas of the council, and other key partners like colleges and health. Our meetings are hosted at RBH offices and chaired by Greater Manchester Combined Authority.

Like most deprived areas, our work started in the context of a mixed legacy of previous initiatives. Looking back a decade, there is more community activity and a great partnership between frontline public services addressing the challenges of a minority of residents with acute struggles and chaotic lives. But after 10 years of national economic recovery from recession, talking today to those in low paid work or unemployment, you get the sense that Rochdale feels like a place where the public services on offer struggle to keep up with evolving social and economic challenges.

A high proportion of people are stuck, involuntarily, in part-time work. On Black Friday, last November, a huge local warehouse took on an extra 1000 workers – but just for the weekend. With developable land and motorway access, logistics makes sense as an economic development priority for Rochdale. Although this work is physically demanding, and people worry about an automated future, the convenience of ubiquitous 24/7 online shopping by definition requires inconvenient working shifts, concentrated in places like Rochdale. The cumulative impact on people’s expectation of work is serious. “I’m not fussy about the job I do”, said 19-year old Devon, who wants to run activities in a care setting, but currently works in a cafeteria.

For many people in Lower Falinge and College Bank, health issues determine their access to benefits which support their income. As far as Sarah is concerned, a stable benefit payment without conditions, nor the potential for penalties and sanctions, is welcome. The support to find work appropriate to her health limitations risks, if successful, disrupting her benefits.

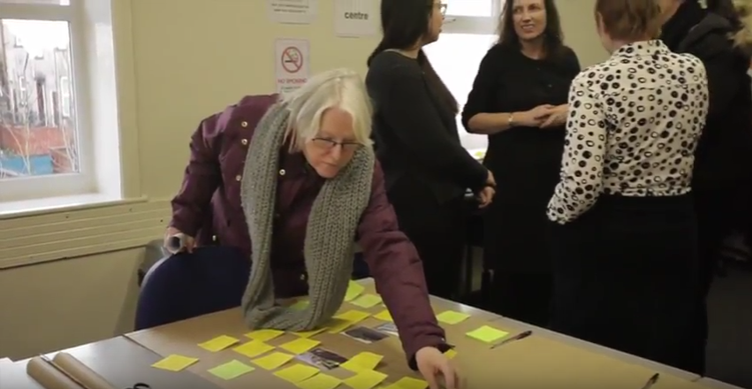

At every stage of our work we have been listening to, and asking questions among, residents of Lower Falinge and College Bank. Public service design in this complex context would be very challenging without this kind of design process. After 18 months, we are now finalising a proposal that will seek funding to address some of the particular local challenges. It will be aimed at those people left behind by the local labour market and current welfare system.

We call this the New Pioneers Programme. It will involve careers brokers who are involved intensively in people’s lives, with caseloads under 15, meaning there’s time to meaningfully support people to co-defined goals. It will involve an alternative income provision, asking some people to exit DWP benefits and join and independent locally administered scheme, underpinned by reciprocity rather than sanctions, penalties and conditions. And it will need a space to meet, talk, plan, learn and share – a space for new kinds of work including remote working, regrouping between gig economy jobs, and pursuing self-employment and enterprise. It will also be a space for the New Pioneers themselves to support one another.

It has become very popular to talk about ‘place’ in the context of public service reform. This Rochdale programme will be designed around the needs of a neighbourhood, designed to make the most of what you can do when the people your work with live in the same community. In this programme, people won’t just be fellow service users, they will be neighbours pursuing a range of career goals, be that an increase to full-time hours, a volunteering placement in a new industry, a permanent contract or someone’s first paid job.

At the local scale, sustaining outcomes through continued contact, beyond the ‘intervention period’ becomes easier – people are more likely to remain in touch, because, simply, they live around the corner. We want to view this as an experiment, though we don’t want this language to scare residents away from signing up to be a part of it.

As housing estates all over the country need physical renewal, we need new approaches to ‘people’ alongside new designs for ‘place’. It is only by trying new things, responding to the (extensive) feedback about what isn’t currently working in the country’s most deprived estates, and evaluating initiatives thoroughly, that we can recover the pride we want to have in regeneration as a profession.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

One of the biggest missing ingredients in many of these efforts that I have seen in the US is having the right people around the table to help shape ideas for programs, actions and indeed the physical places that give form to the environments people inhabit. Most of these fail people and communities in very measurable ways because the people most qualified to understand and help to shape policy and strategy and translate them into physical places–architects (not unqualified hacks like "architectural designers")–are often kept well away from these important deliberations. Why? Because for some reason the public and the media think that all architects know is how to draw buildings. Wrong.

Despite all of the prominent initiatives in green building, sustainability and transit oriented development, many regions of the world continue to be blighted by a race to the bottom in the quality, durability and performance of our built environments. It’s spurred largely by our banking and real estate development sectors whose legislated and self-imposed incentives cause them to remain focused almost entirely on the extraction of short term profits to the exclusion of all other considerations. I have no problem with folks making legitimate money but when the vehicle for doing so is something so fundamental to human wellbeing as the places we inhabit, costly social, economic and environmental consequences are more often than not the result. More often than not these results occur because developers tend to do everything to cut corners so as to generate bigger profits. Leaving out the people with the qualifications and experience to help in Place Making yields similar results in wellbeing, fulfillment and opportunity as would be the case if, after 7 or 8 years of education and professional training, physicians and nurses were told that their career was to launder surgical greens and that the critical diagnostic and treatment decisions were being developed by others.