The RSA’s Public Services and Communities team, part of the Action and Research Centre, has launched a new ‘prospectus’ setting out its future programme of work.

'People, Public Services, Power and Place' (pdf, 11KB)' is an ambitious plan to put reducing inequality at the heart of our work to create more inclusive economies, more innovative public services and more sustainable places. It is launched alongside fascinating new polling data showing unexpected support for higher taxation.

Since I started working at the RSA in May this year, I have made it my mission to go out and listen to the ideas and concerns of its 29,000 fellows who are distributed quite literally across the whole globe.

No other think tank has such a broad base of policy wonks. No other ‘do-tank’ has such a prolific network of innovators. And it seemed natural, for an organisation so deeply committed to democratic reform and community agency, to put our principles into practice and attempt to co-create the strategy we want to guide our work.

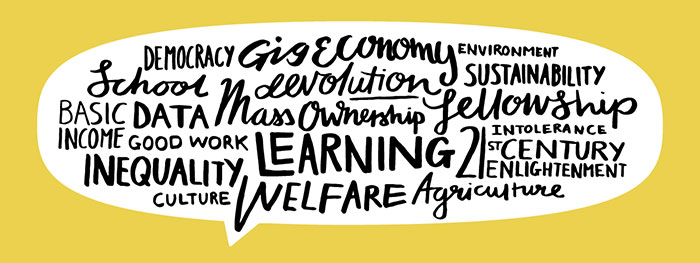

Over the course of hundreds of conversations and Fellowship meetings, 8 participatory workshops right across the UK, and a number of themed webinars involving fellows from overseas, it has been fascinating to crowdsource an agenda for change.

We shaped our conversations around the idea that just as William Beveridge, back in the 1940s, constructed his ideas for the 20th century welfare state around the notion of tackling Britain’s Giant evils. In exploring the relationship between state and society in the 21st century, so we asked people about the Giants looming over Britain today. And it was remarkable just how much consistency there was in people’s responses.

Although the language varied from place to place and person to person, it was fairly easy to identify 5 clear themes: inequality, intolerance, isolation, disempowerment and climate change. And what was perhaps most striking of all was the prevalence of one word above all others: inequality.

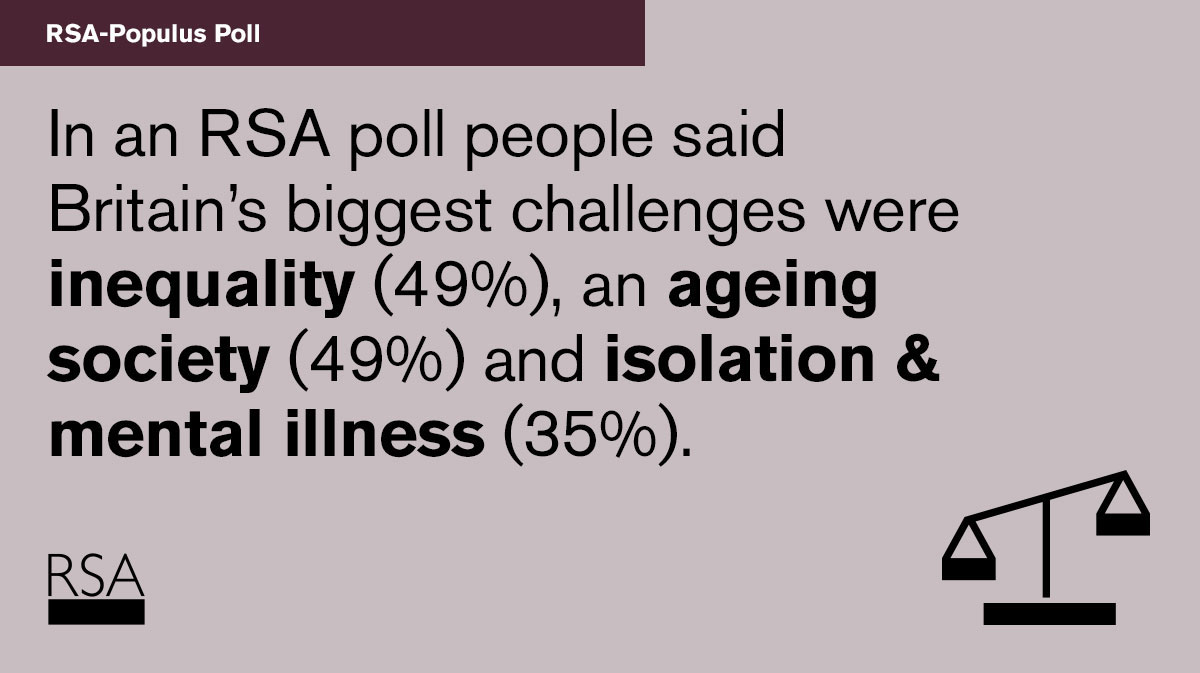

We were so struck by this, we decided to carry out a public poll and we commissioned Populus to carry out a survey of over 2,000 people to test what they felt to be the biggest challenges facing the nation. We gave them 10 options and asked them to select three and the results were surprisingly similar. The top answer, chosen by 49% of all respondents, was inequality. This was very closely followed by our ageing society. And climate change came in at 35% too - a particular concern for younger people. Given our current context it is also interesting to discover that only 33% thought Brexit and international relations were of particular concern.

We also asked people if they were prepared to pay higher taxes to address some of these challenges and remarkably 41% said they would, compared with only 14% who said they wouldn’t. The rest weren’t sure. Within this there are some fascinating nuances. Young people were the least likely to back higher taxation with only 30% of 25-34 year-olds and 33% of 18-24 year-olds supporting higher tax and increased public spending compared with 54% of those over 65. There is clearly some enlightened self-interest at play here. And if patterns of public expenditure persist, any increases in public expenditure risk widening the inequalities they might be intended to reduce.

While health and social care spending is clearly a national priority, if it continues to consume the lion’s share of public spending – and any public spending increases – then young people will remain wary. Furthermore, our polling shows that young people seem to lean away from fiscal redistribution as the main means of achieving social justice in favour of volunteer-led social action and equal opportunities.

Our listening exercises and polling make two things clear: First, public service transformation must break down silos and focus more effectively on tackling the social and economic determinants of ill health and social isolation, not least in reducing economic insecurity. And second, we need a more sophisticated account of the relationship between ‘welfare’ - the role of the state – individual opportunity and communal social action.

To this end, we have committed ourselves to a new ‘change aim’:

Our vision is of a society where citizens, businesses and governments work together, in policy and in practice, to tackle inequalities of income and wealth, of health and well-being and of place, power and exclusion: a new social settlement that reconciles welfare with opportunity and social action.

Join the conversation (19th November - 10th December) a series of powerful conversations looking at the change needed in our democracy, education and economy

We set out a range of new ideas for research and action, set out under 4 themes: people, public services, power and place. And we are wanting to energise a number of critical policy debates about how much tax we should be paying for our public services; about how to drive a devolution revolution; and about bring deliberative democracy into mainstream British politics.

Our more participatory approach to fostering a 21st century enlightenment doesn’t stop here. We are determined to build on the ideas and activities of Fellows as we seek to tackle the Giants that loom large over contemporary Britain and whose equivalents can be found in almost every nation of the world. And so we are inviting as many people as we can to get involved with our programme of work whether via Twitter, via collaborative action or via sponsoring our research programme. Do drop us a line and accept our invitation to be partners in change.

- Britain’s New Giants [long read] Tackling Beveridge’s ‘5 giants’ defined the British welfare state. The RSA & RSA Fellows have defined 'Britain’s New Giants': Inequality, Disempowerment, Isolation, Intolerance, & Climate Change. Ed Cox explores how the modern state can solve these problems.

Related articles

-

Counting on recovery: collecting the data to inform policy post-crisis

Tom MacMillan

We’re starting to gather evidence on community responses to the pandemic, to help shape post-crisis policy. If you are too, let’s team up.

-

How to be a public sector entrepreneur

Ian Burbidge Neil Reeder

The traditional top-down approach of driving change in the public sector feels slow and inflexible. Innovation requires a willingness to draw on ideas, even ones ‘not invented here’.

-

How can we support social entrepreneurs to help improve health outcomes?

Ian Burbidge Mark Swift

What is the role of community organisers and social entrepreneurs in transforming public services and improving population health outcomes?

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

This so resonates with me. My top SDG is #9 Reducing Inequality. This is because I believe that all other issues stem from this, from over-consumption and climate change to wellbeing and mental health. Most world issues are caused not by a lack of resources but a lack of distribution.

If there's anything I can do to support this work, I'd love to hear.

Firstly I'll declare my age bracket: 30-34

And my sector: Digitisation in construction

On the topic of disruptive technologies, like the ones I'm involved in, and with all the kinds of workshops and events I attend, like CDBB, IET, etc... I find myself asking the same question which is: "great!, we will improve efficiency, everyone can do their work quicker with less mistakes, but when the demand for Our work doesn't bloom and fill up Our spare capacity, what do We do next? Taking it to its final conclusion where all work is automatible, how do the goods and services that machines produce get demanded when consumers are unable to consume due to unemployment and precariousness? If your workforce is machine rather than labour, are you not potentially destroying GDP without careful policy consideration? Are you not destroying your government's tax base?"

Matthew Taylor is well known in this topic within the circles of the RSA, yet when I mention this in my line of work I get blank RSWhat? MatthewWho? and poorly considered responses to my enquiry: "they'll find something else to do"; is the most common answer.

The rate of debate, implementation of the policy around this area has to match the rate of disruption these technologies are being developed. I believe the idea of 'machine taxes' has to be debated on national and international levels like the kind that Bill Gates and the US have begun but relatively unsuccessfully to date.

There are many reasons why employers will want to follow automation, improve consistency, speed, etc putting aside the immediate financial gains that can be had in adopting them. Tax on machines (in the broadest definition including software on computers that displace labour) will not be the kind of deterrent that advocates who wish to profit from automation argue. Such advocates may want to profit from the redundancy of labour within their business but this short term goal is not sustainable once the consumer base itself erodes into redundancy. Short term competitive advantages don't answer long term sustaining of that model.

So onto this topic, I say both, fund the NHS and all other universally needed services, but let's take a closer look at that tax base and what is threatening it, (in my opinion automation) and redefine what labour is so that what it is being substituted by, substitutes all the functions of labour including tax obligations. Use automation to reduce waste as it often promises. Frame the questions this way, and the under 45s responses might not be as different from the over 45s when they realise it won't necessarily be them paying the taxes.

This contribution focuses on key issues. But two obvious points are worth making. One for approx 250 years people have argued that machines replace labour and unemployment results. Never happened. We have more people

Thanks for the reply. I recognise that point and it may persist for a while but not necessarily indefinitely - I have some cautionary thoughts on that.

It wouldn't be possible to predict all future events solely based on occurrences in the past. I'd take care in expecting the same result each time from a technological advancement when circumstances in a complex system are very unlikely to be equal in every respect - as you mention population size is one of those variables that holds high unpredictability.

The differences here is the speed at which these disruptions will happen whilst people's response to adaptation is fairly consistent limited by our human capacity for change (our conservative nature). We also have an erosion of leadership - particularly acute in Britain - but also occurring throughout the OECD nations and the emerging polarisation of ideology. I've seen comments at the bottom of UK newspaper blogs in recent years comparing now to the 1930s, but whilst there are similarities, there are some significant differences between now and then too. We rarely tread the same footsteps each time we walk along a path - we always have the potential to change direction at any step. I believe this is true here too for better or worse.

The population peak is something that will need to flat line (as the late Hans Rosling predicts) so we can't rely on expansion of labour indefinitely, and indeed the rapid decrease in birth rate in the early 70s in much of the western world will see an equally rapid reduction in tax base in the next 10-15 years. We (as David Attenborough put it) can't rely on a model of infinite growth on a finite planet.

This particular revolution isn't just replacing muscle as revolutions of the past had, it has the potential to replace mind and decision making itself. Some technologies are bridging the interaction gap between virtual and physical. Previously machines needed operators, programmers, thinkers, but once the machines can autonomously perform all of the tasks to optimise and innovate its own hardware software to efficiently deliver its purpose, its very different to the machines that were spinning cotton in Manchester or cultivating land in Mexico.

Will people find something else to do? Yes, but if that something else is poorly distributed across society, it could end up being not quite the utopia the technology promises. We certainly would want to avoid the more radical consequences that history does show us when technology is used to disempower rather than empower people.

If the substitution of machines in any way exacerbates the problem of reducing the tax base and the means for governments to redistribute wealth throughout society, then the substitution will have to mimic all aspects including the economic ones of labour or it will be a very uneven society indeed.