As the summer holidays began, the Department for Education released its latest data on school exclusions from the academic year 2017/18.

There is reason to be optimistic about the deceleration in the rate of school exclusions over the last academic year for which data is available. However, rates of exclusion are still rising, and most concerning is the disproportionate number of children living in poverty, with special educational needs, and from certain ethnic minority groups who are excluded.

The school exclusions issue is not just one of total numbers but of educational equity and social justice.

Pupils receiving support for special educational needs are five times more likely to be expelled from their school, and poor children attending primary schools are six times more likely to be kicked out of school, with no hope of return to that school, than their peers.

five key findings from the new school exclusions data

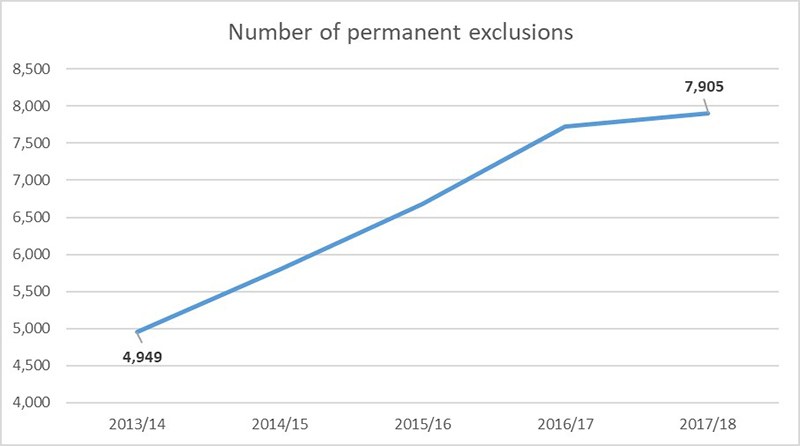

1. Permanent exclusions continue to rise, but not as sharply as in previous years

7,905 children and young people were permanently excluded from English schools in the academic year 2017/18, never to return to the excluding school. On average, that’s 42 pupils expelled every school day.

There has been a steep increase over the last five years, with the total number of permanent exclusions increasing by 60% since the academic year 2013/14, when the total stood at 4,949.

However, the rise in permanent exclusions has slowed in the last year for which we have data. From 2016/17-2017/18, there was 2% increase in the number of pupils expelled from school, compared with the 15% year-on-year increase reported last summer.

Permanent exclusions from primary schools have, in fact, fallen by 3%. However, expulsions from secondary schools have risen by 4% over the same period.

It is hard to know for sure why the rate of permanent exclusion has begun to slow. Some may say we’ve reached the upper limit because there are only so many pupils within the school population in any given year who exhibit behaviours that lead to exclusion. Others may attribute this deceleration to the increased scrutiny of the use of permanent exclusions brought about by the government’s Timpson Review, local authority scrutiny reviews (such as this one in Islington), and recent media coverage. The data doesn’t reveal the reasons for this change, but the RSA is interested to explore this through the Pinball Kids project.

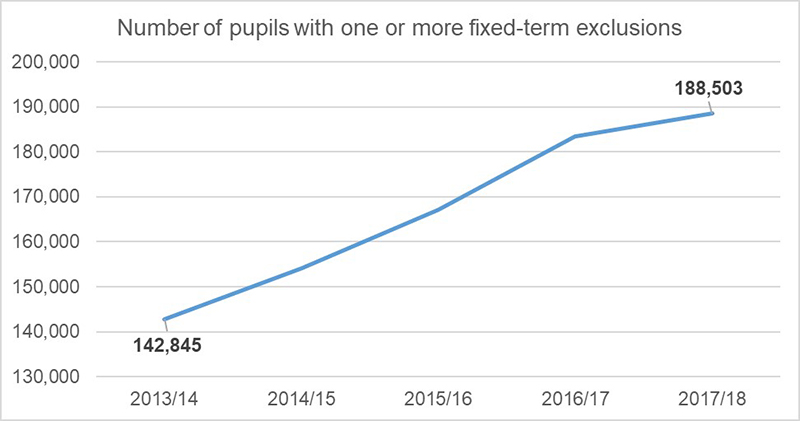

2. The rise in fixed-term exclusions continues

Over 410,000 fixed-term exclusions (temporary suspensions) were recorded in the academic year 2017/18.

This represents an 8% rise from the previous academic year and a 52% increase since 2013/14. The increase over the last academic year is slightly less sharp than previous years, when increases have consistently been around 12%, but it is still large.

There are many potential explanations why fixed-term exclusions are rising. Some may relate to accountability. For example, if schools are judged almost exclusively on academic progress and results of pupils, schools may use fixed-term exclusions to ensure that a few disruptive pupils don’t impede the academic progress of the rest of the class.

In the autumn, the RSA will be publishing the results of a survey with NFER to explore, among other things, the circumstances under which teachers would remove children from class or use an official exclusion and the conditions that would prevent the need to do so. This could offer us some indications of the drivers of rising suspensions.

In 2017/18, over 180,000 pupils experienced a fixed-term exclusion from school. This means that 32% more pupils were suspended from school last year than in 2013/14. The graph below demonstrates the trend of increasing fixed-term exclusions over the last five academic years:

Of course, suspensions are not distributed evenly across the population with some pupils receiving more than others. 12,323 pupils received more than 5 fixed-term exclusions during the academic year 2017-18. The average duration of a fixed-term exclusion was 2 days, but 4,151 exclusions lasted a whopping ten days or more. This is a significant amount of learning for a pupil to miss out on in a school year, and it is all the more troubling if you consider that pupils with special educational needs and those from poorer backgrounds are more likely to be missing out on this opportunity to learn than their peers.

As previously noted by the RSA, exclusions may also have a substantial impact on the parents and carers of affected pupils. Some parents interviewed for the project spoke of having to give up work, and therefore jeopardising their family’s financial security, in order to supervise their child while off school.

3. Children with special educational needs and disabilities are disproportionally represented in exclusions statistics - especially among our youngest excluded pupils

Pupils who receive support from their school for their special educational needs (those registered as receiving ‘SEN support’) are five times more likely to be permanently excluded than their peers with no recorded needs. In total, over 418,000 pupils with (diagnosed) special educational needs and disabilities were excluded over the last academic year. The majority of these were pupils with speech, language and communications needs (61% of permanent exclusions and 53% of fixed-term exclusions).

The pattern is strongest in primary schools. A staggering 83% of all permanent exclusions from primary schools were for pupils recorded as having special educational needs.

While most exclusions continue to be given by secondary schools, there are concerns about the growing number of very young children being excluded from school and appearing on the rolls of Pupil Referral Units (schools for excluded children). This new data from the Department for Education shows that last year over 500 pupils were permanently excluded before they reached their eight birthdays and over 1,250 of pupils had been expelled before they turned 11 years old.

The fact that so many of those younger children excluded have special educational needs underlines the urgency to revisit special educational needs funding and support for schools. We hope that the Department for Education Review on funding for children with special educational needs and disabilities, which just closed their call for evidence, will help find some answers.

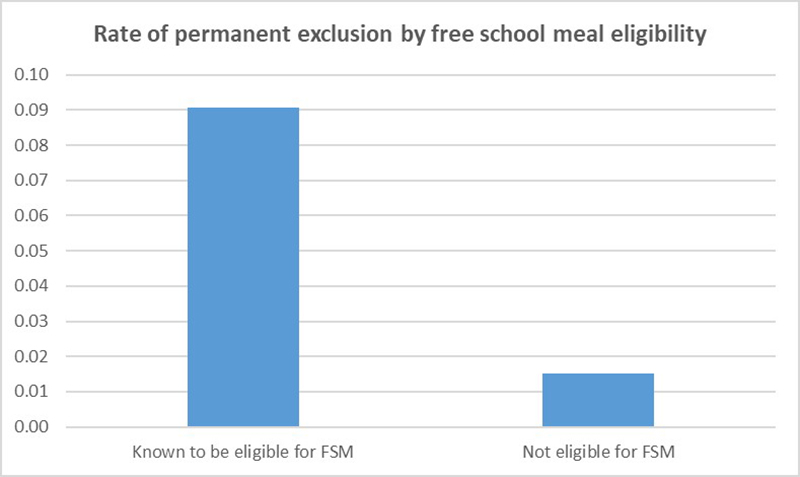

4. Exclusions are undeniably a social justice issue

Pupils eligible for Free School Meals were four times more likely to be permanently excluded from school than their non-eligible peers.

Deprivation is an even stronger predictor of exclusion at primary level. Primary-aged pupils eligible for Free School Meals were 6 times more likely to be permanently excluded from school than their non-eligible peers.

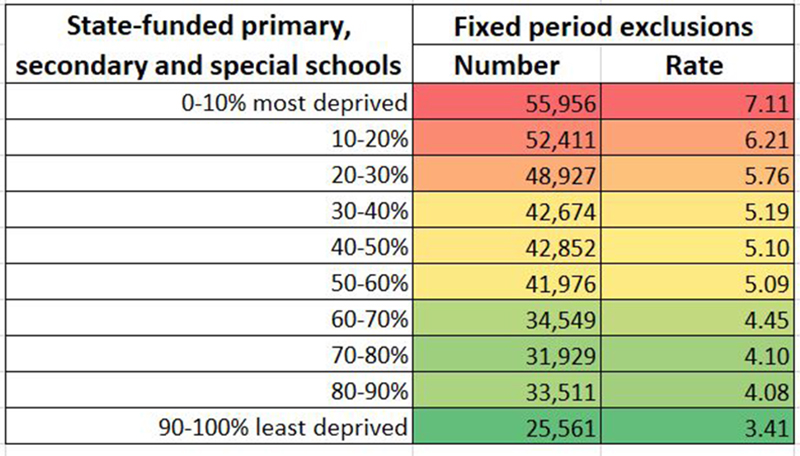

A less important, but also interesting, patterns appears when you look at areas of high deprivation. There is a strong correlation between attending a school in an area of high deprivation and being excluded from school as demonstrated by the table below:

Pupils from schools in the 10% most deprived areas are roughly twice as likely to be excluded as their peers from schools in the 10% least deprived areas.

The disparity is greatest in primary schools: pupils from primary schools in the 10% most deprived areas are roughly five times more likely to be permanently excluded than their peers from schools in the 10% least deprived areas. Of course, not all children living in poverty live in deprived areas, therefore the pupil-level data about pupils eligible for free school meals is more relevant to our considerations of the link between poverty and exclusions.

Pupils from some ethnic groups also continue to appear disproportionately in exclusions statistics. The rate of permanent and fixed-term exclusions is highest for pupils from Gypsy Roma and Irish traveller backgrounds. Meanwhile, Black Caribbean boys are nearly 40 times more likely to be permanently excluded from school than Chinese boys.

5. Some types of schools are more likely to exclude than others

Looking at the total number of exclusions by school type, it appears that exclusions from local authority schools decreased over the last academic year. This data, however, doesn’t tell the whole story.

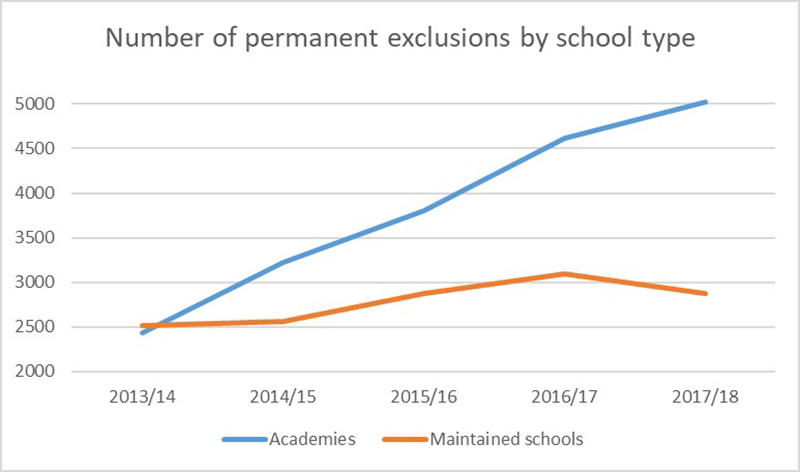

The total number of permanent exclusions from maintained schools decreased by 7% from 2016/17 to 2017/18. The number of permanent exclusions from academies rose by 9% over the same period. This is part of a wider trend since 2013/14:

It is important to read treat this data with some caution. As the DfE note in the narrative accompanying the data:

the majority of secondary schools are academies, and secondary schools tend to have higher rates of exclusion than primary schools.

According to the National Audit Office, 68% of state secondary schools were academies in 2016/17, and this rose to 72% by 2017/18. The rise in the total number of permanent exclusions from secondary schools over the same period was 4%.

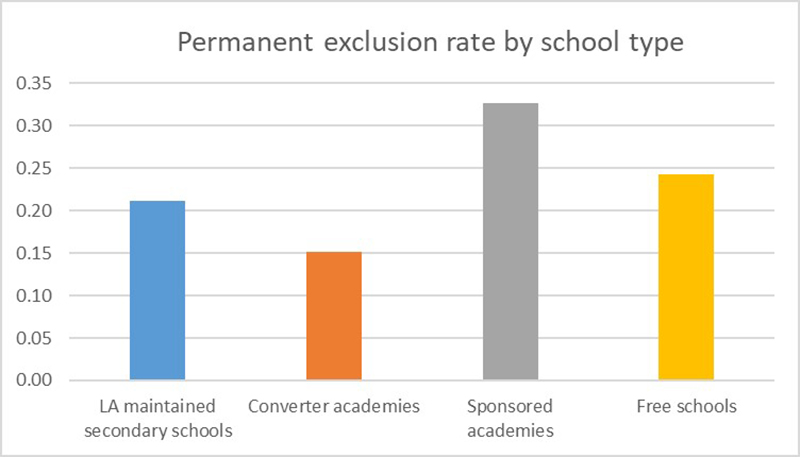

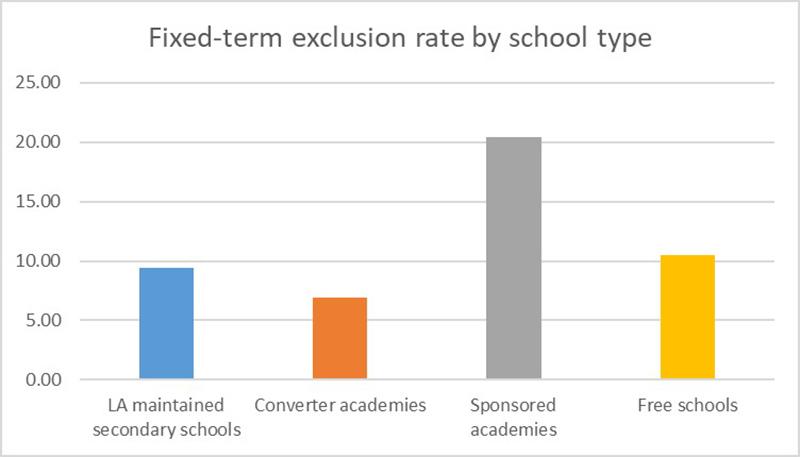

These facts alone are not very telling, so it makes sense to look more closely at rates of exclusion as a proportion of the total population of students attending each type of school. Rates of permanent exclusion from local-authority-maintained secondary schools and secondary academies are very similar (both 0.2% rounded).

However, there are important differences between permanent exclusions rates from sponsored academies and maintained schools. Pupils are 1.5 times more likely to be permanently excluded from a sponsored secondary academy than a maintained secondary school, and twice as likely to be fixed-term excluded.

Rates of permanent exclusion from primary academies are double that of maintained primary schools (0.4% and 0.2% respectively). Rates of permanent exclusion are highest from sponsored academies (0.6%).

Sponsored academies are typically underperforming schools that are matched with sponsors as they convert to academies as part of their “school improvement” journey. Head teachers and local authority representatives have reported to us through interviews for the RSA’s Pinball Kids project that exclusions rise during “takeover” processes where new academy sponsors take over the management of previously “failing” schools. This is a theme that the RSA is keen to explore further through the Pinball Kids project and in future work.

Education isn't getting fairer anytime soon

The educational experience of children does not look to be getting fairer any time soon. To take one example, over the same period that we have seen a rise in school exclusions, which disproportionately affect children from deprived areas, child poverty has been increasing. Relative child poverty is expected to rise further still in coming years, with the Institute for Fiscal Studies estimating that 5.2 million children will be living in poverty by 2022. Their projections are based on the assumed impact of benefit reforms. If such policies are pushing a greater number of children to be at risk of exclusion from school – something that we don’t yet know enough about – this would surely create an impetus to reconsider these reforms.

If you have insights about patterns of school exclusion, underlying causes and potential solutions, the RSA’s education team would love to hear from you. You can get in touch on pinball.kids@rsa.org.uk and a member of the team will try to get back to you as soon as possible.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

Hi Laura, I think this article is really striking. I am interested in the exclusion rate by school type - do you have the original source for the graphs you produced? Thank you!