As the economy has evolved over the last decade, a perfect storm of austerity, automation and e-commerce has created winners and losers, with women in particular bearing the brunt of job losses in back office and high street roles. But the start of a new decade warrants a healthy dose of optimism. What new jobs will emerge? And how can we support workers to transition into the jobs of the future?

The future of work is coders and carers

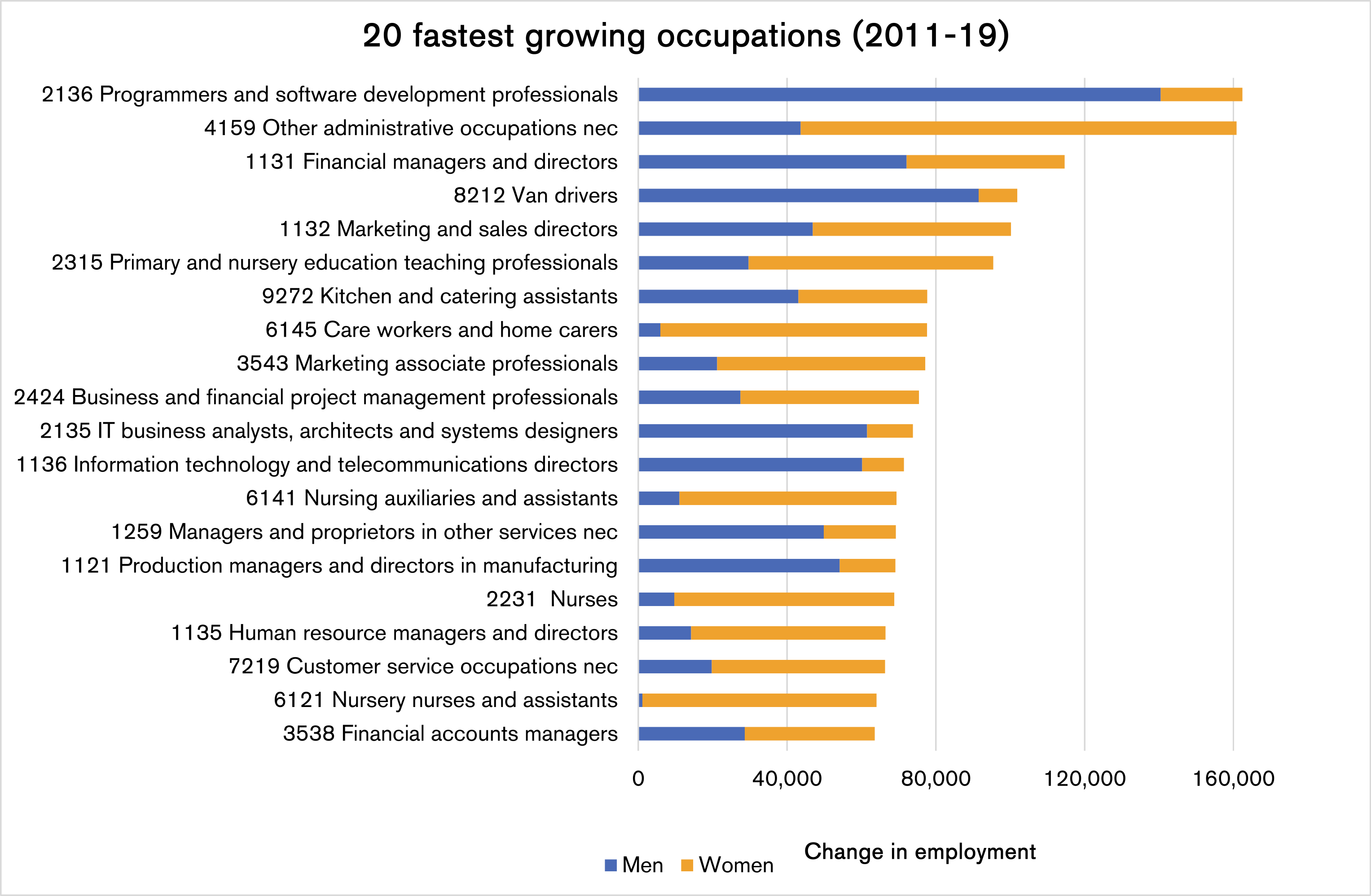

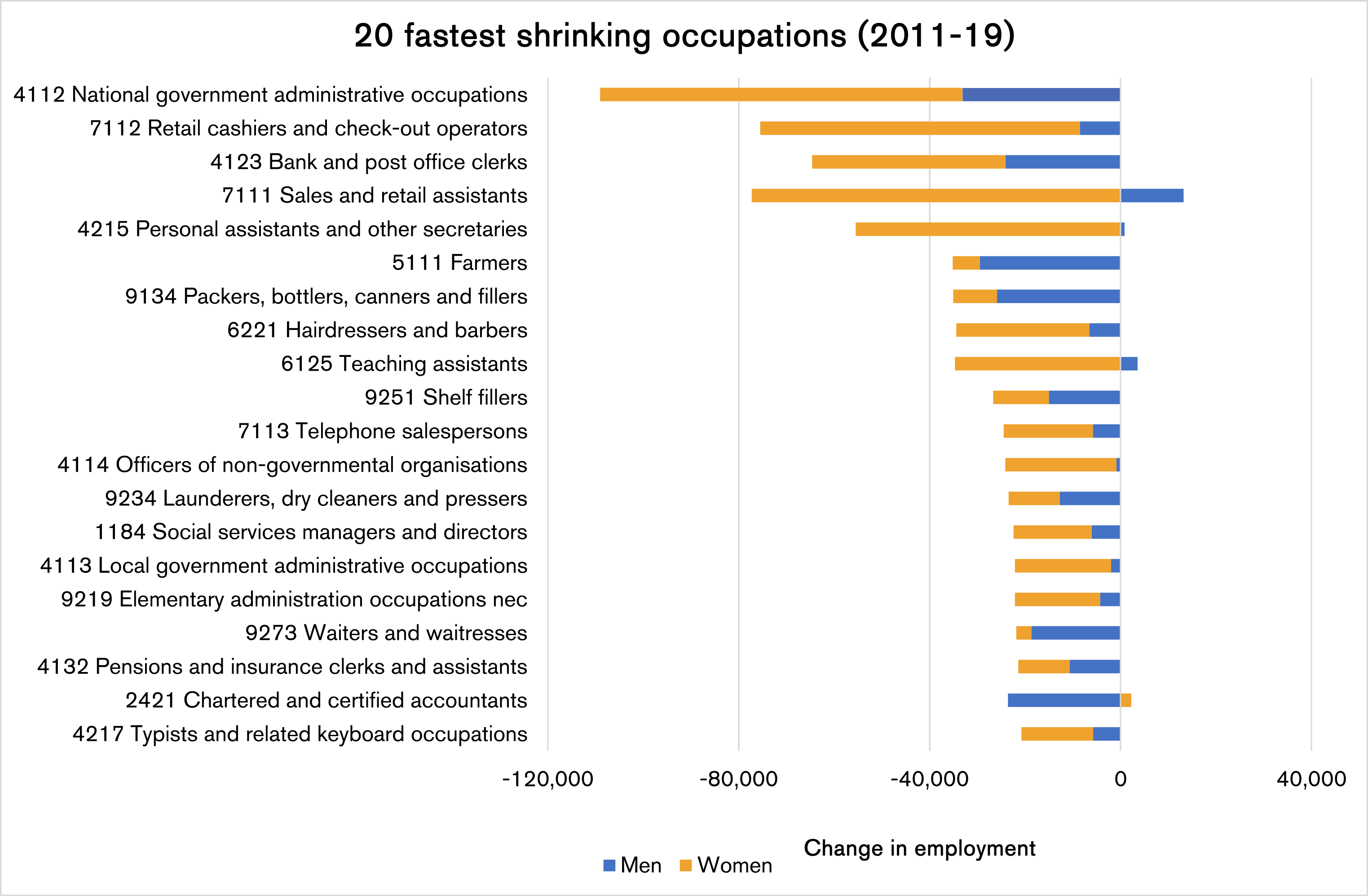

We analysed Labour Force Survey data to understand what the fastest growing and shrinking jobs were between 2011-19, in terms of their net change in total employment.

It may come as little surprise that programmers and software developers were the fastest growing occupations, with over 160,000 new roles created (a 72 percent increase from 2011). IT directors and business analysts were also in the top 20 fastest growing occupations. But unfortunately, the cliché of ‘tech bros’ is entirely warranted: less than 20 percent of these flashy well-paid jobs were filled by women.

Expect to see more of these hi-tech roles in the 2020s – as the tech giants look set to disrupt traditional industries such as healthcare and finance.

We have also seen a growth in hi-touch jobs. Primary and nursery school teachers, care workers and home carers, nurses and nursing assistants were also in the top 20 fastest growing occupations. These roles are also gendered, with the vast majority being filled by women. The growth in these roles is in keeping with changing demographics, particularly an ageing, ailing population – a trend which is almost certain to continue into the next decade.

The death of the high street

The top 20 occupations that have seen the biggest losses include many traditional high street jobs, such as retail sales assistants, check out cashiers, bank and post office clerks and dry cleaners. 289,000 high street jobs were lost over the last decade, 81 percent of which were held by women. Previous RSA analysis suggests that the death of the high street is also having a disproportionate impact on regions outside of London. Back office roles, such as administrators in government, personal assistants, telephone salespeople and pensions clerks are also in long-term decline.

Blame austerity. Blame automation. Blame e-commerce.

What jobs could these workers be doing in the 2020s?

Jobs of the future

We expect these trends to continue into the next decade. But to predict the jobs of the future, we may need to do more than simply look at the past. For many are yet to widely exist, let alone be classified in official statistics.

In the RSA’s Four Futures of Work report we used a method known as morphological analysis to map out different scenarios for 2035. This involved drawing on expert opinion to identify high-impact, highly uncertain drivers of change, from technological progress to the health of the global economy and future of the trade union movement. We then explored the different ways these ‘critical uncertainties’ could play out over time and interact with each other.

While these scenarios for the future of work are not exhaustive predictions, they present a wide range of plausible outcomes in a way that is vivid and easy to grasp. Each offers a glimpse of the different kinds of jobs we expect to see in the next decade.

- The Big Tech Economy: technology develops rapidly, leading to widespread automation and tech companies tightening their grip on traditional industries. More coders and agile project managers are needed. New jobs in the tech ecosystem would also emerge; for example, lawyers who deal with claims against driverless cars. There may even be drone delivery drivers and virtual reality experience designers.

- The Precision Economy: technological progress is moderate, but sensors are widely adopted by businesses. Resources are allocated with much greater precision. Workers are subject to new levels of algorithmic management as gig platforms break into new sectors. This expansion of big data calls for more analysts to crunch the numbers, while behavioural scientists and gamification experts design addictive apps to squeeze every last drop of juice out of workers.

- The Exodus Economy: another economic recession causes technological progress to stall. Alternative economic models gather interest as people give up on consumer capitalism in search of more sustainable lifestyles. Job losses are felt in industries underpinned by consumer spending. But occupations such as upcycled clothing designers and community energy managers go mainstream.

- The Empathy Economy: technology is stewarded responsibly. Dirty, dull and dangerous jobs are automated as emotional work becomes more important. Jobs growth is seen in traditional ‘empathy’ industries such as education, care and entertainment. New roles emerge, including personal brand and digital detox consultants to help us manage our relationship with social media, while retail workers pivot to become “in-store influencers” who are highly knowledgeable about brands and able to deliver authentic experiences.

How to help workers transition

Women have borne the brunt of jobs lost to automation and austerity in the last decade, as well as missing out on the best-paid new jobs. At the same time, a recent OECD study has warned that low-skilled workers at risk of automation are three times less likely to participate in training than those in jobs more resilient to technological change. These workers face a double whammy. We need to do more to help them transition into the jobs of the future otherwise they will be ‘left behind’.

There is no silver bullet here, but the UK should take note from best practice from around the world.

Both France and Singapore are piloting personal learning accounts, which give all workers annual training credits that they can spend on accredited courses. Personal learning accounts are a ‘portable benefit’, independent from employment arrangements – meaning the credits accrued are retained by workers even if they move jobs or become unemployed.

In Sweden, employers pay into funds to provide workers with an end-to-end transition service, following collective redundancies. Organisations known as job security councils provide displaced workers with information about their local labour market, as well as coaching, training opportunities and financial compensation. This makes Sweden’s economy more dynamic. Businesses can more easily shed unproductive labour because unions can support job cuts, knowing that workers will be protected.

New jobs will emerge in the 2020s – from coding to caring, and new roles rooted in sustainability. But for workers to transition we will need a robust approach to upskilling and reskilling. Lifelong learning is one key pillar of the new social contract that we must build backing for. In the next few months, the RSA will be publishing a report outlining a blueprint for this social contract: a set of interlocking rights and responsibilities, for state and society, that can drive good work and economic security, now and in the future.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

I understand the concepts and like the general approach ... but there are several issues thgat make me pessimistic for the UK (and the world):

I fear that the perspective is too parochial - national rather than global - so countries with a higher productivity (from China to Germany) will use technology variously to continue to improve productivity and maintain employment leaving countries with a lower productivity (for the time being, the 'United' Kingdom) more and more uncompetitive as we under-invest in education, new technology, and innovation, and with an ever-shrinking economic base.

I also fear that coders / analysts / consultants are appraching saturation - we can't all be coders or analysts, and the further danger with consultants is that they become part of the low-paid uncertain gig economy.

I also fear that becoming a carer is not a panacea for unemployment - carers are both poorly paid and have poor workiong conditions - and caring is susceptible to technology - viz the Japanese push to develop robotic carers (even 'empathetic' carers) as the 'young people' population declines and the older population increases.

Finally, it would be good to see an employment analysis of the various scenarios - what jobs might be needed and in what quantity?

It would be interesting to understand where these growing occupations are manifesting themselves. Are the IT related occupations being freed from geographical constraints or is the state of UK Internet infrastructure still resulting in need to migrate to certain urban areas in order for people to take advantage of those opportunities?

Need for Florence Nightingale to raise status of Care workers. A next door neighbour is now unable to leave her house but she has an excellent team of care workers. When we visit we are most impressed by the quality of care and the ways in which the care workers seek to improve their clients life. Care can be rewarding job if the care workers are properly trained and given status.

When Florence ventured into nursing it was terrible. By involving middle and upper class daughters and training them rigorously she raised the status of nursing and turned into not a profession.

Home care and residential home care has to have a similar transformation . Standards, training and status. This will be expensive but otherwise those needing care end up in dumps.

For the old with assets this care can be affordable. The average time in residential care is about a year for men and 18 months for women. Anyone with a house should be able to afford high quality care for this period. Our neighbour can afford this quality of care since she has provided that after her death any proceeds of the sale of the house will go to a local charity. This avoids family pressure.

A good place to start raising care quality would be for those who can afford it. Once standards and performance are goo then pressure will arise for this quality to provided by the state for this who cannot afford it.

With our ageing population there will be need, and with finance a demand, for a great increase in numbers of care workers and with training and status many displaced workers will find new worthwhile careers.

Fascinating. Clients of my marketing and PR agency include multi academy trusts and care companies, I am also a school governor so this makes for interesting reading. We have just seen our first male teaching assistant employed at one of the trust primary schools and this move is echoed in the job losses graphic above with the number of women in TA roles negative whilst male TAs have increased. I think the biggest challenge with this change in future jobs will be finding people to take the roles. Care must be the hardest sector to recruit into, followed closely by subject specialist teachers - primarily maths. I see many great announcements about intent to recruit the volumes into these sectors (more nurses and teachers) but I don't see any clear plan of where to find them or how you convince people to change their perceptions of theses roles/sectors. I think this is the challenge.

Please god, lets hope that in 10 years time, personal brand managers and digital detox consultants are on the list of decreasing job numbers and we just put our devices down or turn them off instead of creating an economy out of the misery it/they cause.

Thanks Fabian, a really interesting and informed insight. I hear a lot of talk about the impact of high-tech on high-touch and well may it be so over the next decade. It seems to me, however, that when the baby-boom-bubble pops its clogs the high-touch industries are likely to have their own 'high street phenomenon'. Admittedly this mid-baby-boom-boomer is not likely to see the end result play out but I may well get to see the start of the slide as high-tech moves in and we (baby-boomers) move out.