The cash census is a new RSA report examining the UK’s evolving attitudes and behaviours towards cash and digital payments. In this blog, researcher James Morrison takes a closer look at regional differences in cash use and the relationship between cash use and deprivation.

The cash census

Explore the use of cash in an increasingly digital economy.

Cash use has been declining for years but 2017 marked an inflexion point. It was the first year in which cash was not the most popular form of payment method, having been overtaken by the debit card. These two dominant means of payment continued their inverse trajectories in the years that followed. Though as recently as 2013 the number of cash payments was more than double that of debit card payments, by 2019, debit card payments were more than 50 percent higher than cash payments.

The pandemic has since accelerated this trend. In 2020, card payments (both debit and credit) formed a majority (52 percent) of payments as both vendors and consumers preferred to use lower contact payment methods to reduce the perceived risk of coronavirus transmission in the early part of the pandemic. The decline in payments was matched by a decline in cash withdrawals. In 2020, there were 669 million fewer cash withdrawals compared to the previous year, representing a decline of 40 percent.

Regional differences

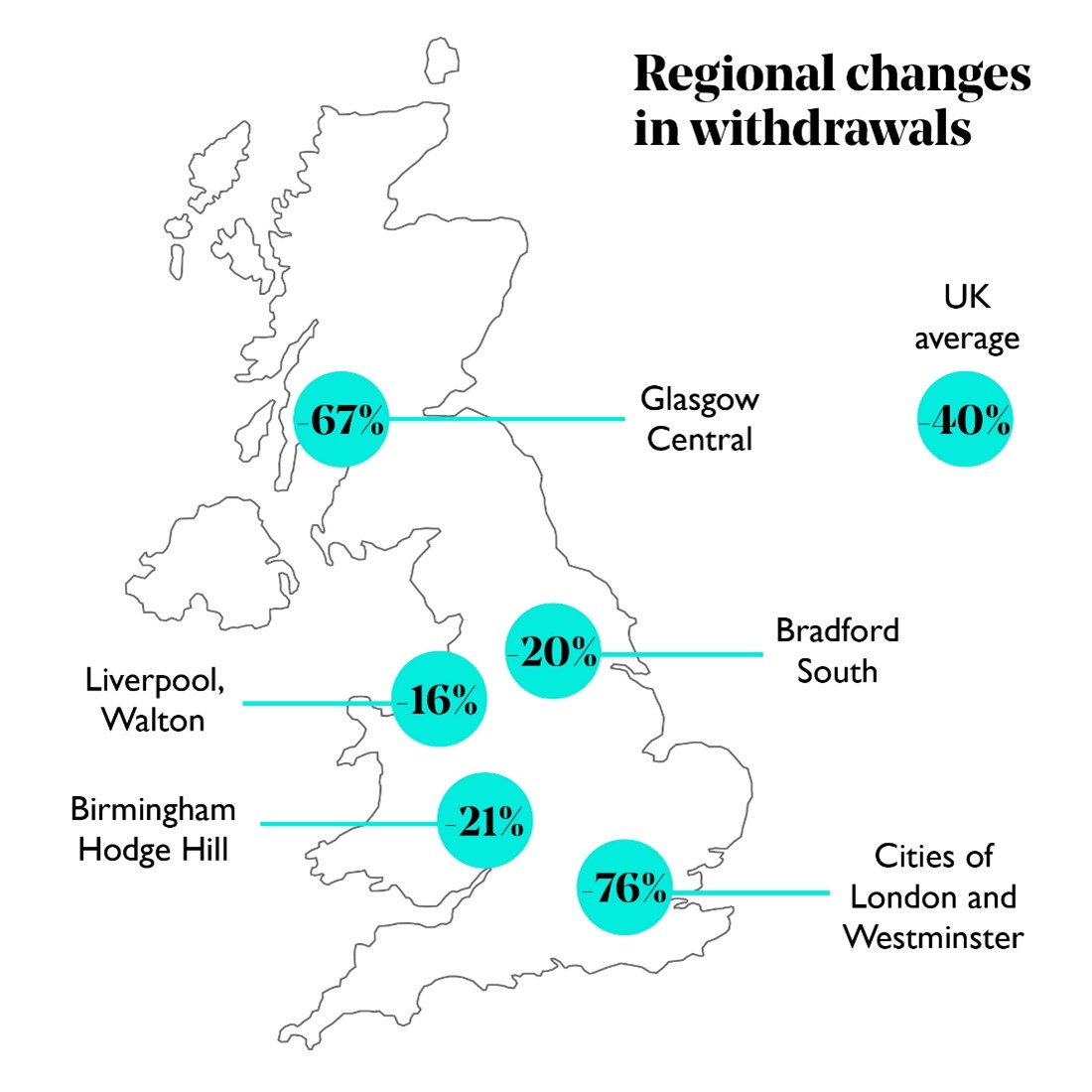

The decline of cash, however, is not universal across the UK. There are strong regional disparities in cash use and changes in cash infrastructure. The South West saw the highest year-on-year decline in cash withdrawals in the first year of the pandemic with a 45 percent fall. In contrast, the West Midlands and the North East saw the smallest falls (38 percent).

Local differences in cash withdraws are more apparent at the constituency level and show which areas remain more reliant on cash. In February 2022, the average fall in cash withdrawals across the UK was around 40 percent. By contrast, in some of the most deprived areas, the figure was half of this, at 20 percent.

Payment method of choice

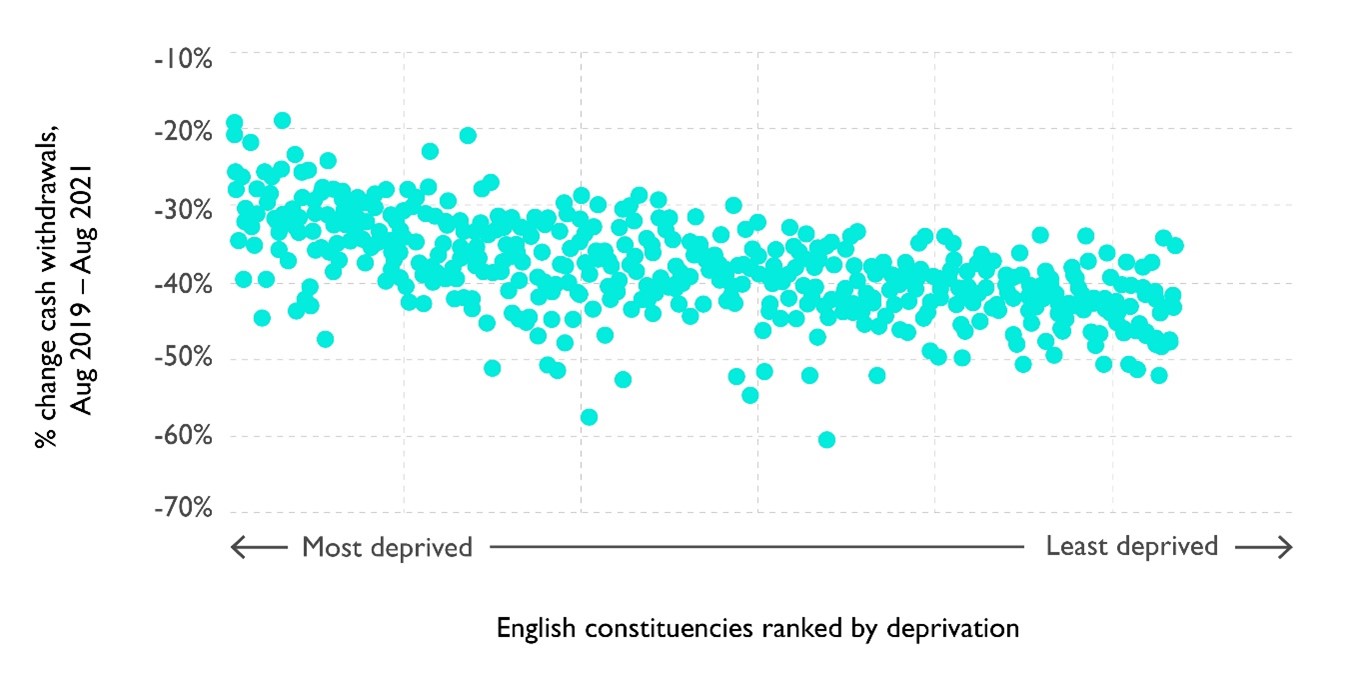

There appears to be a connection between changes in cash use and deprivation. Data on the change in the number of cash withdrawals between the financial years 2019-20 and 2020-21 shows that all five (and eight of the top 10) of the parliamentary constituencies that saw the lowest fall in the number of withdrawals during the first year of the pandemic are in the top 10 percent most deprived constituencies in England.

Liverpool, Walton was the parliamentary constituency that saw the lowest fall in cash withdrawals. That number fell by 16 percent, compared to a nationwide change of -42 percent. In addition to having the most stable rate of cash withdrawals across the first year of the pandemic, Liverpool, Walton is also ranked as the most deprived constituency in England, in terms of health deprivation and disability and employment and is second in terms of income. This pattern continues to play out further down the rankings. Bradford South, which saw the second-lowest fall of 20 percent, is in the top decile of deprivation, ranking 29th of 533 constituencies. The second most deprived constituency, Birmingham Hodge Hill, saw the joint-third lowest decline in cash withdrawals at 21 percent.

This graph shows there is a negative correlation between the change in cash withdrawals and the level of deprivation. As a rule, the least deprived an area is, the greater the shift away from cash. This adds weight to the 2019 Access to Cash Review’s concerns that a switch to cashless would disproportionately exclude many people who already face substantial barriers to economic inclusion.

Supply v demand

When looking at these trends and the decline of cash in general, we must resist the temptation to ascribe patterns exclusively to a change in consumer preferences in the face of widespread technological advances. The decline of cash has been accompanied, and perhaps facilitated, by an erosion in cash infrastructure. Between 2017 and 2021, the UK lost almost a quarter (23 percent) of its ATMs. Most regions lost between 20 and 25 percent of their ATMs in this period. The outlier was Northern Ireland, which lost only 13 percent. Even so, in the same period, Northern Ireland lost 21 percent of its free-to-use ATMs. London lost three in ten of its free ATMs between 2017 and 2021. Though people may increasingly want to use other forms of payment, it has been getting more difficult each year for consumers to access cash.

In the last few years, it has been common to hear people lamenting the closure of their local bank branches. This anecdotal evidence is borne out by the statistics. Between 2017 and 2021, the UK lost 25 percent of its bank and building society branches. Scotland has lost the highest proportion of branches, seeing a decline of almost a third (31 percent) in this period. These have hit older users the hardest. Though overall branch use has declined significantly, it remains higher among older people. Our survey also found cash use higher among older people, with one in three (32 percent) over 55s reporting that they wouldn’t be able to cope in a cashless society.

Our research also grouped people into five segments according to their responses to issues such as these. Explore them in our interactive data visualisation dashboard.

Maintaining payment methods for all

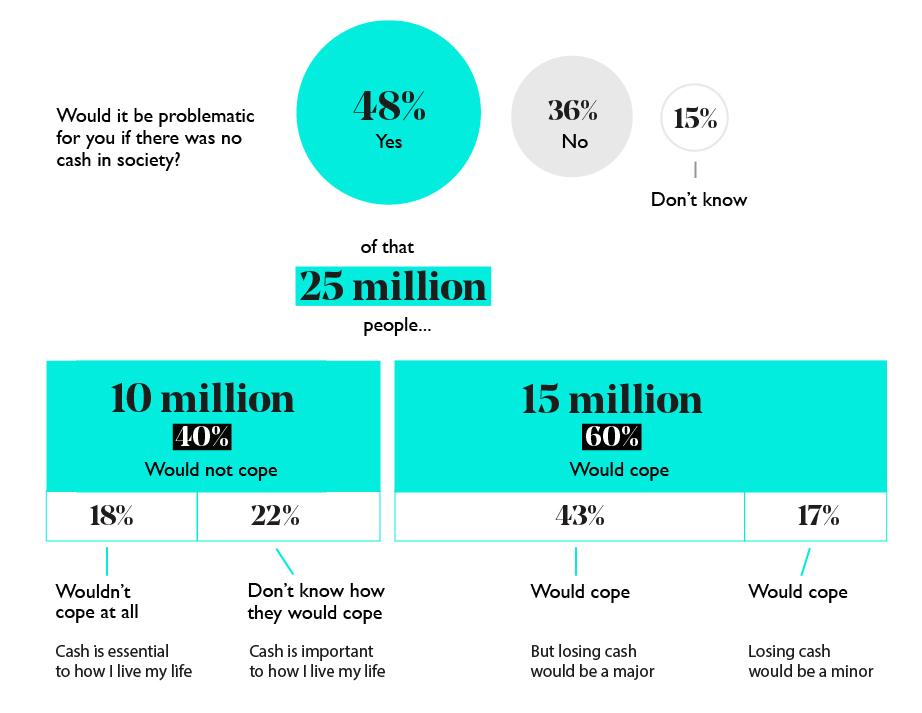

The decline of cash payments, which has led to higher per-transaction costs, threatens the sustainability of cash infrastructure and the closure of ATMs and bank branches is a symptom of this. However, our research has shown that millions of people in the UK still rely on cash in day-to-day life. 25 million people think a cashless society would be problematic and 10 million are unsure of how they would cope or would not cope at all.

The financial infrastructure on which millions rely cannot be abandoned. The government must bring forward its promised legislation to protect access to cash, based on the principle of maintaining the ability of people to make payments in the way that works best for them. Even if access to cash is protected, digital payments will continue to increase.

Digital financial literacy should be taught to young people and financial service providers should offer training to people of all ages so that everyone can develop the skills to confidently manage money digitally. There have been positive recent innovations in consumer banking services, such as banking hubs, which bring new cash depositing services to communities, and legislation to enable purchase-free cashback. The industry should continue its good work and collaborate to offer high-quality sustainable services to communities – but this must be backed up by a commitment from government to protect cash.

What does this change in behaviour by region mean for the different demographics of the population and the wider economy? How will society have to adapt as we move to a cashless economy? Share your views in the comments section below.

- Explore how those in your area use cash in our regional interactive data dashboard.

- Read the full report, The cash census, and explore our final recommendations.

- Want to find out more? Register for our event, Is Britain ready to go cashless?, on 12 May 2022.

Related articles

-

The cash census

Report

Mark Hall Asheem Singh James Morrison Aoife O'Doherty

This new piece of RSA research explores the use of cash in an increasingly digital economy.

-

Is Britain ready to go cashless?

Blog

Mark Hall

RSA research examines Britain’s relationship with cash and digital payments that shows 10 million people would struggle in a cashless society.

-

Is Britain ready to go cashless?

Research & Impact Event

Online

As digital payments and banking boom, is Britain ready to go cashless? Join our webinar to discuss the future of cash.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.