In the first lockdown the RSA coined the phrase 'building bridges to the future' to describe how learning, adaptation and innovation during the crisis might shape and prefigure a better future.

Over the last ten months we have tested these ideas with a wide range of partners turning categories and propositions into concrete examples and proposals. We are nearing the end of the bridge, but what do we want to create on the other side?

The nighttime economy has seen as much carnage as most sectors through Covid-19 due in part to the impossibility of social distancing. DJs and producers, denied their audience and the means through which they showcase their talents, faced a bleak future. Many of the lesser-known were already finding it difficult to make ends meet before the crisis hit. In April some DJs such as Solarstone, Lange and the Thrillseekers quickly pivoted, spotting the opportunity to use Twitch, primarily an online gaming platform, to share broadcasts of live mix sets, which in turn enabled greater interaction with their audience and provided a subscription-based income stream. They have spent less time travelling between gigs and more time composing and producing new music, as well as offering older tracks on vinyl for the first time. In turn, these DJs have been mixing vinyl again, showcasing a seemingly fading art form prior to the pandemic (vinyl sales in 2020 were the highest for nearly 30 years). Creators and audiences are finding opportunity and community amid the chaos, a lifeline of hope during an otherwise destabilising and demoralising period.

Innovation and change arise from disruption to the dominant patterns and habits that comprised the status quo. The more critical the shock the more energy is released and the less able we are to ignore it; obvious faultlines are exposed but also, if we look and listen closely, we can notice what might be new foundations.

The faultlines revealed by the pandemic are diverse: inequality in all its often intersecting forms; the impact of austerity; conflicting moral perspectives between the primacy of the individual or the collective; the weaknesses of a globally-interconnected economic structures; and the opaque and nepotistic approach of the UK government to private sector partnership and procurement.

Foundations can be seen in new-found respect for our teachers and delivery drivers, in a greater solidarity with our neighbours, in car-free streets and rivers flowing clear. They can be seen – for a period at least – in accommodation being provided to those living on the streets, in less wanton consumerism and more mindful consumption and in more agile and collaborative public services as digital becomes the default. The bricks and mortar for new foundations were there before the crisis but urgency and shared purpose has started to bind them.

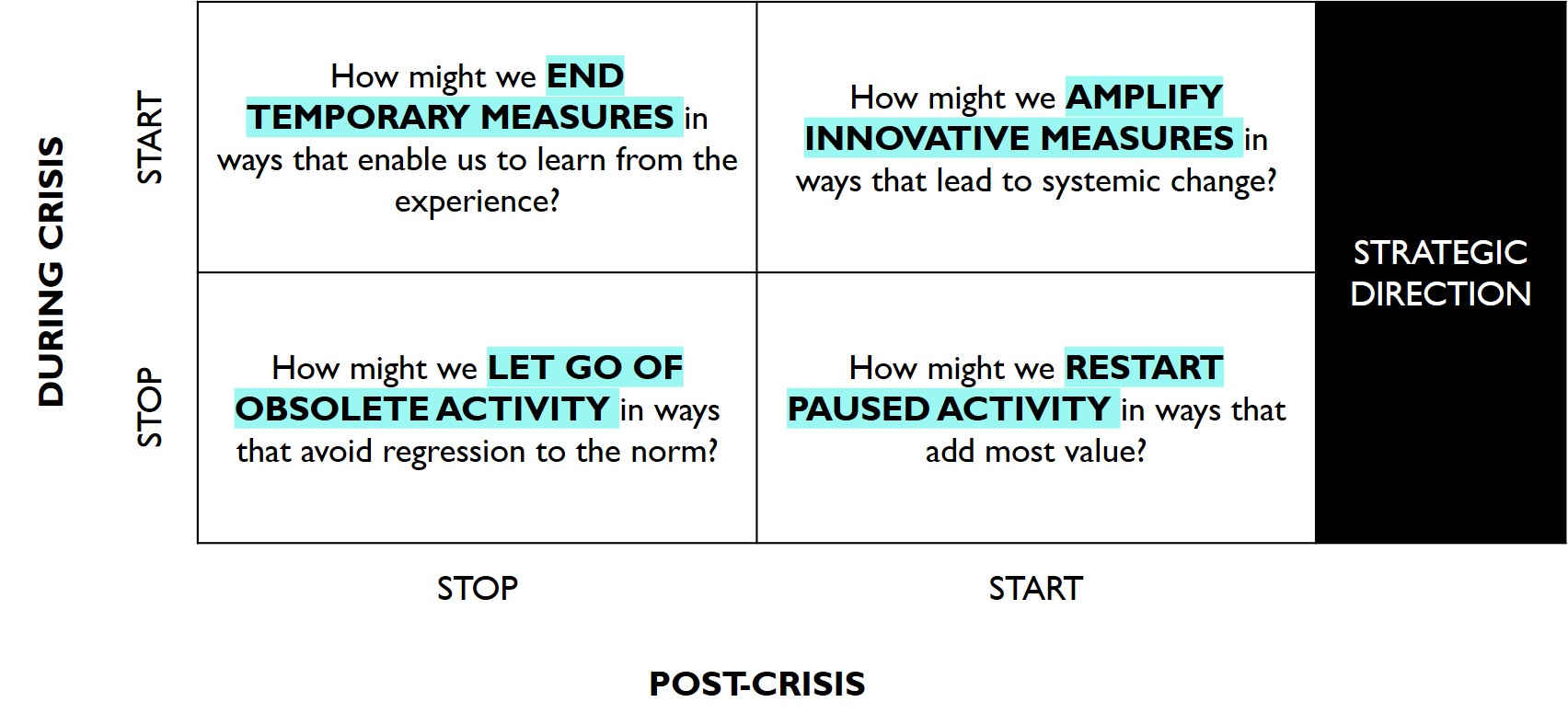

The RSA Future Change Framework was developed early in the first lockdown to help people capture and reflect on these insights. We heard about change but could see early on this was not simply a process of some things being abandoned while others flourished, nor was there much spare energy to think about whether crisis-driven adaption could or should be sustained. We identified four broad categories of response:

Some crisis responses are temporary measures, while others might prefigure new ways of doing things beyond the crisis. Some things we halted were practices and processes that were already obsolete but too baked into our systems to easily change; now we have a legitimate opportunity to let them go. Other things are on pause, but we will likely restart them in a completely changed context.

Some crisis responses are temporary measures, while others might prefigure new ways of doing things beyond the crisis. Some things we halted were practices and processes that were already obsolete but too baked into our systems to easily change; now we have a legitimate opportunity to let them go. Other things are on pause, but we will likely restart them in a completely changed context.

It has been a privilege to see how colleagues in the public and community sectors have found value in this framing and utilised it in their work. For example, we worked with a group of social entrepreneurs in the North West of England. They were deeply concerned about the impact of Covid-19 on vulnerable members of their communities. As the founder of a charity dedicated to helping young people avoid a life of crime explained“for most of our young people home is not home as we know it. Home to them is injurious and chaotic. We have extended support hours and also offer support to family members who have few parenting skills. Our service delivery is now remote, this has meant no working face-to-face, no mentoring in schools etc. Our sole focus has been to continue engagement and keep children and young people safe”. Others in this group saw the opportunity to stop doing some things: “We’ve realised that there was a lot we were doing that wasn’t necessarily economical in terms of time and money. Some aspects of business as usual are in place because that’s what we have always done”.

Listening to staff from across NHS Lothian we heard not only of pride in the speed, agility and commitment of their Covid-19 response – “the acute sites pulled together as different disciplines offering specialist services to fellow colleagues, patients and families” – but also about innovations staff wanted to amplify. For many, this was based on a greater understanding of community and inequalities: “We need to continue to build more empathy with our communities”. This focus on seeing the wider system included a desire to improve things from a patient perspective: “Triaging calls with patients prior to appointments helped us to ensure they were on appropriate pathways”. Learning as well as working together was seen as important: “This allows us to compare and contrast working practices across our organisation, look in detail, learn from each other, develop our own tools and methods and try things out in a supportive environment”.

A session with SUSTAIN, the alliance for better food and farming, highlighted the importance of food systems: “Particular changes have seen food redistribution charities adapting and scaling their work; this has been very important for meeting existing need. New services have been set up in response to crisis, from one-to-one shopping services, social check-in calls and partnering to provide hot meals to older people who aren’t able to cook”.

Barry Quirk, Chief Executive at London’s Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea used this framework – part of the RSA's broader Living Change approach – to enable important conversations within his team. He told us “real choices present themselves about the future of adult social care and also about the future of many of the services we deliver. The key word is relevance. What is relevant in an emergency? What will be relevant for the future?”

Barry Quirk's adapated version of the RSA Future Change Framework

Barry Quirk's adapated version of the RSA Future Change Framework

Speaking at an RSA event, Joel Buckholz, Executive Principal of Pimlico State High School in Queensland, Australia shared how he was using our framework with staff and pupils to assess preparations for the next normal: “While it has been critical that we attend to the immediate challenges of this crisis, that alone will be insufficient if we are to ensure that Pimlico can continue to successfully enact our mission into the future”.

Most learning in this crisis has come from action and adaptation rather than theory and planning. The RSA is not at the frontline, but we hope we are helping by giving organisations that are the tools and space to identify and reflect upon the lessons for life afterwards. Drawing on the generosity of those who have used the framework and shared their experiences with us, as well as those with whom we have actively collaborated, we are starting to understand the material that could form the foundations for change.

Both the form and the style of organisational leadership has been hugely challenged and often found wanting (including, of course, in the most powerful job of all). Leaders face higher expectations. The cry of 'why not, we did it in the crisis' will be often heard. As the anti-racism movement following the murder of George Floyd in the US or the support for Marcus Rashford's free school meals campaign in the UK exemplified, there is growing impatience with promises and piety where people want to see action. Many organisations, across all sectors, have had to become less bureaucratic and controlling, more devolved and agile. Yet, so many organisations face big and difficult decisions over the coming period. We still need authority and hierarchy post-Covid-19 but it will have to be based on a greater degree of consent and engagement. As one hassled leader said to us “the old hierarchy is dead, long live the new hierarchy”.

One way leaders have sought to bolster their relevance and legitimacy has been to go to the heart of their purpose. For those with a direct role in the crisis, particularly within sectors such as health, delivery, retail, local government and community, this has meant stripping away anything that seems irrelevant or obstructive to focus unerringly on core business. For others, such as the Slung Low, a charity in Leeds, which went from being a "reasonably busy" community theatre to a "very, very busy" food bank, the crisis has led organisations to rethink how they embody their mission and radically pivot their operational model. Slung Low is one example of many highlighted by Alex Fox in a forthcoming RSA report on 'the asset based charity'.

Although central government has too often abused public hope and trust, the need to achieve and sustain public and stakeholder engagementhas been another recurrent aspect of the Covid-19 response. When important decisions have to be made and adapted quickly, trust and legitimacy are crucial. One large business told us its CEO had gone from a rather stiff quarterly speech to staff to a weekly 'fireside conversation'. It is still the case – as with central government – that this communication is too often one way, but in many organisations expectations of transparency and dialogue have shifted significantly. A healthy democracy requires a vibrant democratic culture, in workplaces and civil society not just formal politics. Achieving authentic creative engagement is about both the principles of power sharing and the concrete challenges of developing and refining processes to sustain legitimacy.

It is action more than words that brings communities together. We have in the last nine months seen much evidence of enhanced local co-operationacross sectors and between organisations, from the initial repurposing of factories to make ventilators and masks to the joining up of local pandemic responses. In her report for the RSA on local public services in the crisis, Joan Munro identified enhanced collaboration as a recurrent theme. As the Chief Constable of Essex, BJ Harrington noted: “We have forged much better working relationships between the local council chief executives, health leaders and ourselves in the crisis. It’s brought people round the table more, and made them more willing to talk about things in order to achieve some outcomes. That will help us in the future.”

In a workshop one of us led in the week before the first lockdown, senior civil servants were asked to identify which was the factor that most enabled, and which was the one that most inhibited, the kind of systemic and agile working they aspired to (what the RSA calls 'thinking like a system and acting like an entrepreneur'). The breakout groups came back the same answer to both questions; process. When processes are poor– bureaucratic, hierarchical, transactional – little good emerges. When they are good – outcome-focussed, inclusive, properly facilitated – energy can be released and channelled. It is natural for day-to-day organisational life to generate barriers and rivalries; the challenge of sustaining purposive collaboration post-crisis needs to be thought about now before old ways creep back.

One benefit of joint working in pursuit of genuinely shared aims is that it can enable faster decisions and responses. Agility and adaptability have traditionally been a challenge across the public sector with its governance and accountability requirements and yet, from the Treasury's policies to prop up the economy, to the way community groups are funded by local authorities, we have seen a willingness to respond quickly and tolerate uncertainty and risk as a price worth paying for action. Even the banks managed to get government-sanctioned loans out to business quickly.

The crisis is also challenging traditional conceptions of what we can control exposing the limits of a mechanistic and deterministic worldview. We need instead to acknowledge and build upon a core lesson of Covid-19, that a complex scenario is not a solvable proposition, that outcomes cannot be predicted; that what happens is an emergent property of the system. This has given us new ways of thinking about the nature of resilience, reminded, for example, of the necessity for redundant capacity.

These are some of the factors determining which of the possibilities and opportunities arising from the disruption of the crisis are harnessed and which pass by. The crisis has given people a new determination to address issues and injustices which were tolerated previously. At the same time as Covid-19 threatens the livelihood of musicians and artists, for example, we are seeing a growing #brokenrecord movement shining a light on the exploitation of music streaming that fails to fairly remunerate the composers of the music we listen to, issues made more salient by the pandemic.

We all hope and pray that the current stage of the crisis will prove to be the darkness before the dawn. But with the NHS under incredible pressure, lockdown continuing and with everyone exhausted by almost a year of crisis (including the false dawn of last summer), hope and energy are in short supply. It would be tragic irony if we were to lose ambition for change just as the end of the immediate crisis comes into sight.

While faultlines reveal structural weaknesses we must address, foundations reveal how things could be. Optimistically they suggest that there are strengths we can build upon, new ways of doing things we can develop further, of a collective energy we can harness. It is more vital than ever that these foundations are recognised because we will need them to help us face the social, democratic and environmental challenges with which we came into the crisis and the economic one that has emerged since.

As the RSA’s Living Change approach captures, there is no prescription for work such as this. We are looking towards the uncertain and the emergent. But just as we will have to ask some very hard questions about what has gone wrong since this time last year, we must also be inspired and guided by how a better future has been prefigured in the Covid-19 response of good people up and down the land. As a participant in one of our workshops said: “nothing is unquestionable; everything can be changed if needed.” The RSA’s partners and friends have helped us imagine a bridge from the past. Now we must lay the foundations for the future.

To correct this error:

- Ensure that you have a valid license file for the site configuration.

- Store the license file in the application directory.

Related articles

-

Open RSA knowledge standards

Blog

Alessandra Tombazzi Tom Kenyon

After investigating ‘knowledge commons’, we're introducing our open RSA standards and what they mean for our practice, products and processes.

-

RSA Catalyst Awards 2023: winners announced

Blog

Alexandra Brown

Learn about the 11 exciting innovation projects receiving RSA Catalyst funding in our 2023 awards.

-

Investment for inclusive and sustainable growth in cities

Blog

Anna Valero

Anna Valero highlights a decisive decade for addressing the UK’s longstanding productivity problems, large and persistent inequalities across and within regions, and delivering on net zero commitments.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.