Employment rates are at a record high. Our economy is good at creating jobs. But what about their quality? Frameworks developed to measure this consist of aspects that include pay, training, working conditions and work-life balance. To what extent are there gaps in good work in the UK? Have these worsened over time? And who faces the greatest challenges?

The pay squeeze

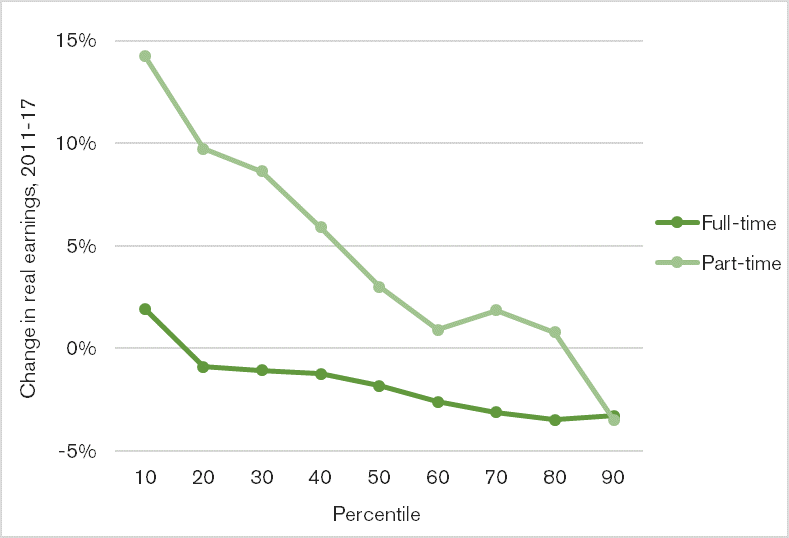

In the years since the recession, workers across the income distribution have seen their earnings decline in real terms. Stagnant productivity growth has left no wiggle room for wage gains while living costs have soared. The lowest paid, particularly part-time workers, have benefitted from increases in the statutory minimum wage (see figure 1). However, too many people (22 percent of employees) still earn below the voluntary Living Wage, which is set at £8.45 per hour (2016/17) and based on a calculation of what is required to maintain a decent standard of living.

Figure 1: Changes in hourly earnings across the income distribution, full-time and part-time employees, 2011-17, CPIH-adjusted (Source: RSA analysis of Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings)

Work-related training has waned

In 2004, almost 30 percent of workers had received job-related training in the preceding three months. In 2017, this figure dipped below 25 percent. And newly released data from the Skills and Employment Survey shows that the average time spent on required training for a job fell from 11 to 8 months over the same period.

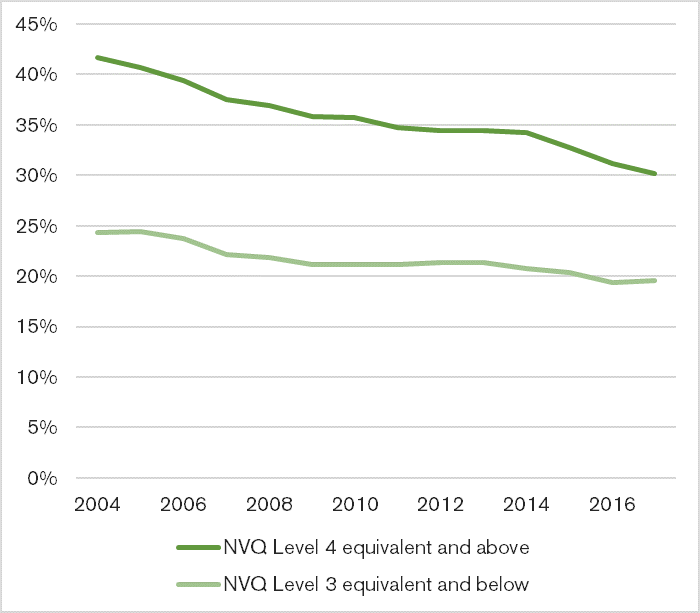

What is more concerning is that work-related training too often remains the privilege of professionals, or those who already have graduate level qualifications (see figure 2). While a recent OECD study warns that workers in highly automatable jobs are three times less likely to participate than those in jobs considered more resilient to technological change.

Figure 2: Percent of workers receiving job-related training in last 3 months by level of qualification (Source: RSA analysis of Annual Population Survey)

Better work-life balance?

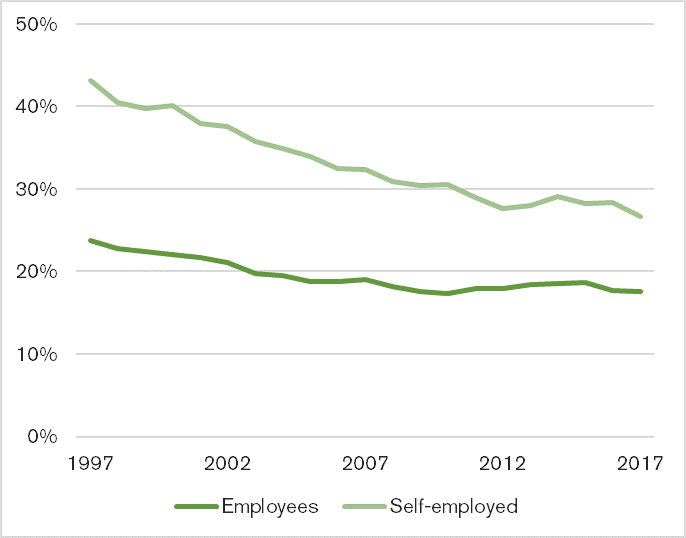

Working hours are an important aspect of work-life balance. And the proportion of people spending more than 45 hours at work has been steadily declining since the 90s (see figure 3).

Recently, much has been made of the growth of jobs that don’t fit the 9 to 5 bill, with part-time self-employment seeing particularly strong growth in the last decade. These jobs naturally enable people to fit work around their other commitments. But it is worth noting that a quarter of full-time employees also have flexible working arrangements such as flexi-time or annualised hours.

It’s not all rainbows and unicorns here. One in ten workers are overemployed, meaning they would happily take a pay cut if this meant they could work less hours. And analysis by the TUC indicates that, through unpaid overtime, 13 percent of workers clock up more than the maximum of 48 hours ratified by the working time directive.

Figure 3: Percent of workers usually working more than 45 hours per week by employment status, 1997-2017 (Source: RSA analysis of Labour Force Survey)

But strained working conditions?

Despite the decline in excessive hours, there has been an increase in work intensity. Between 1997 and 2012, the proportion of workers reporting that they usually work at a high speed (three quarters or more of the time) increased from 23 to 40 percent. While, in 2012, as many as 58 percent of workers reported they usually work under the pressure of tight deadlines.

A more recent RSA survey of workers (2017) shows that 24 percent feel they have less autonomy at work than they did five years ago, with many pointing to technology as the reason for this.

Job strain occurs when demands on workers are high, but they lack control over how to do tasks. The result is an increase in work-related stress – a growing public health problem now affecting 37 percent of workers according to the 2015 British Social Attitudes survey.

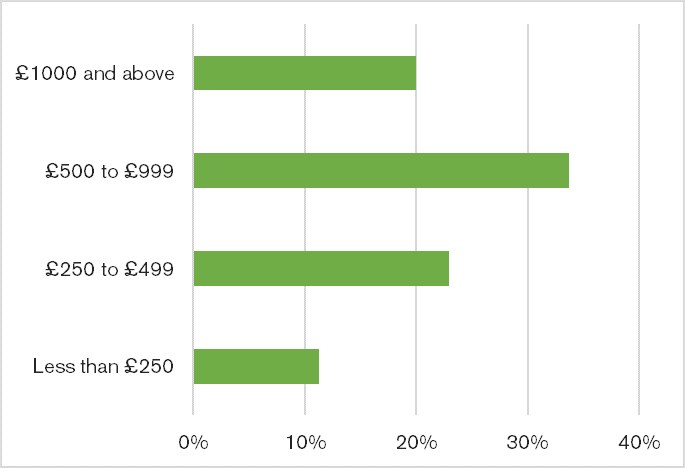

Worker voice - seen but not heard

The decline in trade union membership has been well documented, with density now standing as low as 20 percent. But membership has also become more skewed. Today, members are more likely to be older, middle to higher earners, and public-sector workers. Low paid and atypical workers are much less well represented, meaning unions are often not serving those who need them the most.

And at the organisational level, there has also been a drop off in the proportion of employees reporting that they feel they have a great deal or quite a lot of say over changes to their workplace. The most recent data available (2012) shows that this is below 30 percent, despite more than 70 percent having access to consultative HR meetings.

Figure 4: Trade Union density by weekly earnings, employees, 2017 (Source: Trade Union Statistics 2017, Labour Force Survey, ONS)

Mass insecurity - beyond contract type

Zero hours contracts, agency work, and the emergence of the gig economy have captured the zeitgeist. Their rise has been dramatic in recent years – with each now standing at around 1 million apiece. To put a number on the extent of insecurity in the labour market, commentators often aggregate all workers in non-standard forms of employment to generate headlines such as “More than 7m Britons now in precarious employment”.

This overshoots the mark. Our analysis of the Wealth and Assets Survey shows many self-employed people are income poor but asset rich. Meaning they are economically secure in virtue of their wider household financial circumstances and may voluntarily be pursuing this work because it offers greater flexibility.

But it also does not pay attention to a different group of precarious workers that the RSA has identified in its segmentation of the labour force. Chronically precarious workers struggle with persistent low pay, unfair treatment, poor working conditions and a lack of job security despite being permanent employees. 1 in 7 workers are in this position. They stand in contrast to Acutely precarious workers, who struggle with the uncertainty and volatility we associate with zero hours contracts and gig work.

Find out more about the RSA’s 7 portraits of modern work here

Towards a future of good work

This blog has largely been an exercise in landscaping some of the main datasets that can be used to size up the good work gap in 2018.

The Future Work Centre is a new major RSA project. As part of this, we will seek to better understand the drivers behind these trends and consider how the adoption of and advancements in technologies could further disrupt work – for better or worse. The aim is to develop a blueprint for a new social contract – a set of policy and practice reforms that will help close some of these gaps.

Find out more about the RSA’s Future Work Centre here.

Related articles

-

8 ideas for a new social contract for good work

Alan Lockey Fabian Wallace-Stephens

Alongside the moral urgency of the pandemic, the challenges of growing economic insecurity and labour market transforming technologies require a new social contract for work.

-

Low pay, lack of homeworking: why workers are suffering during lockdown

Fabian Wallace-Stephens Will Grimond

New RSA analysis finds that those least able to work from home are often the lowest paid.

-

Four futures of skills and learning in Scotland

Fabian Wallace-Stephens

What skills will workers need in the future? And how should educators, employers and policy makers respond to shifts in the labour market? We worked with Skills Development Scotland to explore these questions.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.