New RSA analysis finds that those least able to work from home are often the lowest paid. While we are moving towards a homeworking economy, some of the fastest-growing key professions are among the least likely to be able to work from home, such as carers, nurses and drivers.

In December 2019, the RSA published new analysis of the Labour Force Survey, looking at which jobs have grown most rapidly over the past decade. Some of the findings were unsurprising, such as the expansion of programming and professional services. But some were less obvious – ‘hi-touch’ roles have grown alongside ‘hi-tech’ ones, a fact which does not feature enough in discussions about the future of work. During the pandemic, the importance of many of these roles, which include teachers and social care workers, has been brought into focus.

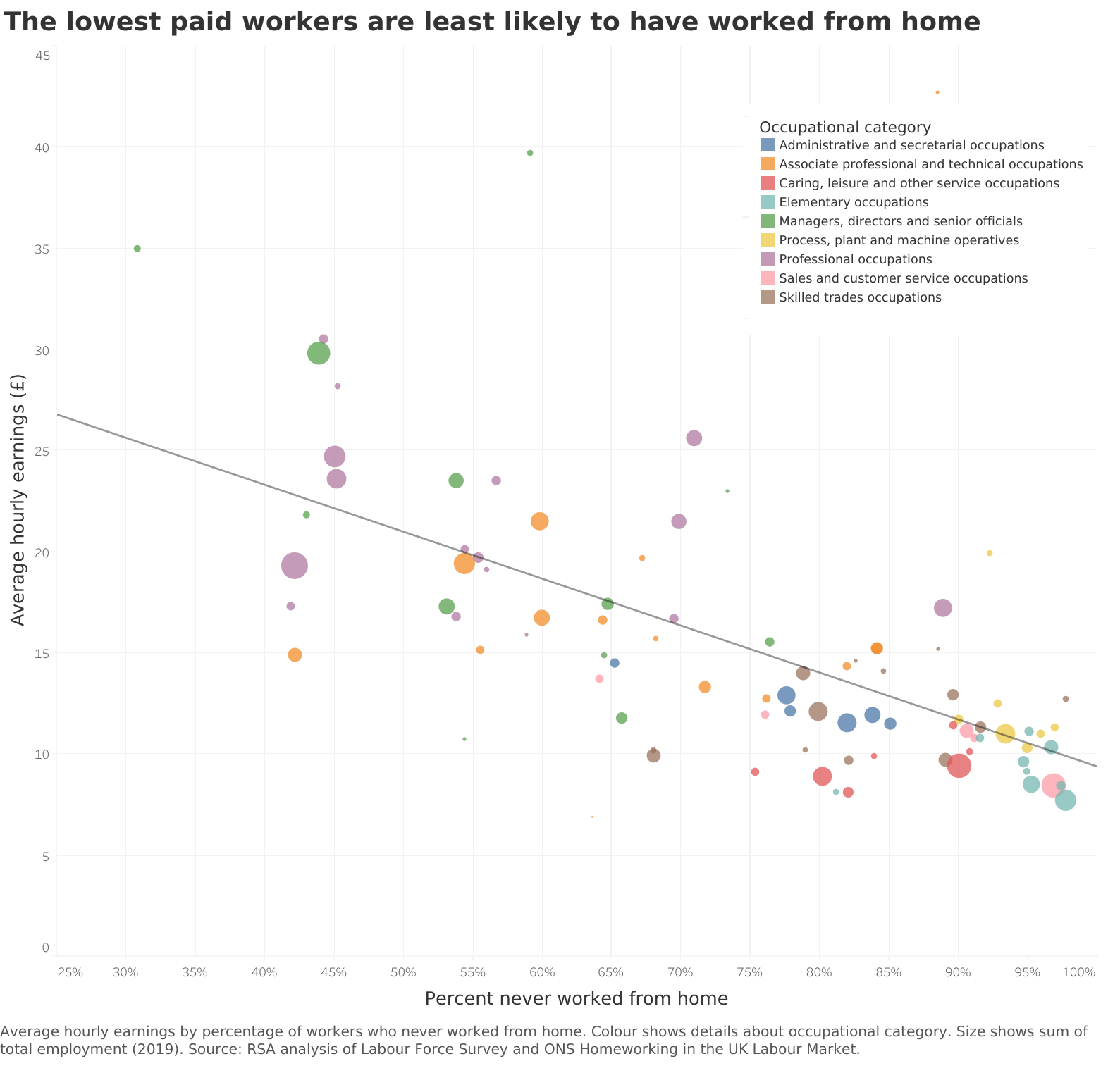

At present the economic picture is grim: the worst predictions suggest that we could see a 35 percent drop in GDP, with millions already having joined the unemployment register. Government advice is that those who can work from home should do so, but for many this is not an option. Using new Office for National Statistics (ONS) data, we have found that those who are unable to work from home tend to be paid less than those who are able to. Our analysis also suggests that while most of the fastest-growing jobs in our economy are those which can be carried out from home, some expanding key worker roles still cannot.

See an interactive version of this graph

WFH is the preserve of professionals

It has been widely remarked that this is a timely pandemic in terms of our technological capabilities: Zoom, ultrafast broadband and Netflix have all made the transition to homeworking more bearable. In many ways this crisis has proven the value of taking up new technologies in the workplace, allowing most white-collar workers to take their work home with them.

Those most able to work from home are likely to be highly paid, and enjoy greater job stability, opportunities for progression, and generous pensions. These professions are expanding; with the help of new technologies, millions of new positions have been created around IT, business, and financial management in the past decade. Around 316,000 new jobs were added for IT professionals, an increase of 41 percent, with over 55 percent having ever worked from home.

Alongside the growth of professional and high-tech jobs, certain hi-touch roles are also expanding (see Table 2). Over the past decade, a quarter of a million new roles were created in caring positions, of which just 10 percent reported that they have been able to work from home. The situation is similar for nurses, another role that has grown to keep up with changing demographics, particularly an aging, ailing population. Road transport drivers and elementary service occupations (eg, waiters or bar staff) are also in this position.

Table 1: Average hourly earnings and percent who have ever worked from home for 20 fastest-growing occupations by net change in total employment

| Occupational category | Average hourly earnings (£) | Percent ever worked from home | Total net change (2011-19) |

| Functional managers and directors | 29.8 | 56 | 476,268 |

| IT and telecommunications professionals | 24.7 | 55 | 315,826 |

| Caring personal services | 9.4 | 10 | 245,581 |

| Business, research and administrative professionals | 23.6 | 55 | 238,763 |

| Teaching and educational professionals | 19.3 | 58 | 234,523 |

| Business, finance and related associate professionals | 21.5 | 40 | 148,793 |

| Production managers and directors | 23.5 | 46 | 145,458 |

| Engineering professionals | 21.5 | 30 | 144,536 |

| Health professionals | 25.6 | 29 | 135,061 |

| Sales, marketing and related associate professionals | 19.4 | 46 | 130,341 |

| Artistic, literary and media occupations | 14.9 | 58 | 129,890 |

| Nursing and midwifery professionals | 17.2 | 11 | 126,069 |

| Other administrative occupations | 11.5 | 18 | 103,344 |

| Road transport drivers | 11 | 7 | 96,391 |

| Welfare and housing associate professionals | 13.3 | 28 | 85,127 |

| Therapy professionals | 16.7 | 31 | 80,035 |

| Public services and other associate professionals | 16.7 | 40 | 72,901 |

| Customer service managers and supervisors | 13.7 | 36 | 68,239 |

| Other elementary services occupations | 7.7 | 2 | 67,493 |

| Animal care and control services | 9.1 | 25 | 60,080 |

Key workers can’t work from home

Our analysis reveals a stark difference in the flexibility afforded to different workers: those least able to work from home tend to also suffer from low wages and economic insecurity. This group includes cleaners, retail sales assistants and several low-skilled manufacturing or warehousing roles (see Table 3). Being unable to work from home puts this group at a greater risk of redundancy, furlough or catching the disease during the pandemic.

Some of these roles are what government has identified as ‘key workers’. Our analysis suggests that many of these workers are being hit with a double whammy of low pay and a lack of flexibility. Those charged with oiling our national infrastructure and looking after the most vulnerable sections of the population are not being remunerated for their work. On average, road transport workers and care workers are paid just £11 and £9.40 an hour respectively.

Retail workers have been key in maintaining supplies of food and essentials during the pandemic, but they are faced with low pay, an inability to work from home, and a shrinking jobs market. Over the previous decade 127,000 jobs were lost by sales assistants and retail cashiers. For these workers, the spectre of automation looms large.

Table 2: Average hourly earnings and net change in total employment for 20 occupations least likely to ever work from home

| Occupational category | Average hourly earnings (£) | Percent ever worked from home | Total net change |

| Other elementary services occupations | 7.7 | 2 | 67,493 |

| Metal forming, welding and related trades | 12.7 | 2 | -21,579 |

| Elementary process plant occupations | 8.4 | 3 | -17,016 |

| Mobile machine drivers and operatives | 11.3 | 3 | 13,039 |

| Sales assistants and retail cashiers | 8.4 | 3 | -126,526 |

| Elementary storage occupations | 10.3 | 3 | 49,595 |

| Plant and machine operatives | 11 | 4 | 18,725 |

| Elementary cleaning occupations | 8.5 | 5 | -57,483 |

| Elementary administration occupations | 11.1 | 5 | -22,766 |

| Process operatives | 10.3 | 5 | -12,369 |

| Elementary sales occupations | 9.1 | 5 | -14,181 |

| Elementary security occupations | 9.6 | 5 | -14,398 |

| Road transport drivers | 11 | 7 | 96,391 |

| Construction operatives | 12.5 | 7 | 18,246 |

| Other drivers and transport operatives | 19.9 | 8 | 16,475 |

| Vehicle trades | 11.3 | 8 | 32,538 |

| Elementary construction occupations | 10.8 | 8 | 7,494 |

| Sales supervisors | 10.8 | 9 | -24,298 |

| Housekeeping and related services | 1o.1 | 9 | -10,560 |

| Customer service occupations | 11.1 | 9 | 33,748 |

| Caring personal services | 9.4 | 10 | 245,581 |

Policy for pandemics

Of course, certain roles cannot take place from home. And we are certainly not in a position where drivers and nurses can carry out their jobs remotely. A flexible workforce is desirable, but for many industries homeworking will remain an unattainable luxury.

Technology is both creating and destroying jobs, with something of a trend towards those that can be carried out remotely. But the future of work is not just about remote working – the trend towards growth in hi-touch roles and other key workers may only increase given renewed emphasis on the value they add to society.

If we say we value key workers, we should put our money where our mouth is. Currently petitions are running to give them all a 30 percent pay increase or at least £15 per hour. In France, key health workers are to be given a bonus of between €500 and €1500, and four million low-income family grants of €150 plus €100 per child. The government should explore similar schemes for workers in the UK. At the very least, we must ensure that promised increases in the minimum wage are not put off because of the impact the pandemic has on public finances.

Those who cannot work from home need a safety net for when they cannot work at all. The RSA has recently called for a temporary universal basic income for the self-employed, to get cash to people quickly during the pandemic and ensure that all workers are supported by generous government schemes. A universal basic income could provide much-needed security for those worst off.

Phasing out of lockdown

This data also has implications for the UK government’s exit strategy for the lockdown. While details have not been provided yet on what this looks like, if the government opts for a phased approach – where certain groups are permitted to return to work – this should be informed by which industries cannot work from home, and by which groups need to return to employment most.

In the longer term, the pandemic will likely accelerate the shift towards homeworking, through both economic imperative and culture change. A mobile workforce will be all the more crucial for building a resilient business and remote working will become more palatable as workforces become accustomed to it. Business travel and commuting will likely decline.

But as with all forms of disruption, there will be winners and losers. We need to ensure that all workers can enjoy good work, regardless of whether they can work remotely.

In the coming weeks the RSA Future Work Centre will be publishing a report outlining a blueprint for a new social contract: a set of interlocking rights and responsibilities for state and society which can drive good work and economic security, now and in the future.

Related articles

-

8 ideas for a new social contract for good work

Alan Lockey Fabian Wallace-Stephens

Alongside the moral urgency of the pandemic, the challenges of growing economic insecurity and labour market transforming technologies require a new social contract for work.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

"for many industries homeworking will remain an unattainable luxury"

There are too many assumptions in this generalisation.

While the data broadly supports the overall point that lower-paid workers tend to be in hands-on and site-specific work, the data is skewed by a number of factors. The largest group who work regularly at or from home are self-employed. Their title of manager or director doesn't mean they are necessarily high paid. Often their income is quite precarious.

There's also a common phenomenon in organisations (which we've found in many surveys prior to implementing workplace change) that managers trust themselves to work form home but not their low-paid e.g. clerical staff who would be well able to do so. Sometimes it's also archaic systems that get in the way of people working from home. I expect these factors will change after the experience of this lockdown.

That homeworking is a luxury - why would this be? These days it's just a normal kind of working. Work gets done wherever it is appropriate to do so. Also, the idea that whole industries won't be able to do it is way off the mark. Even within occupations, different aspects of the same role may be more amenable to working remotely with sensible planning.

That's not to say medics and drivers will work from home/remotely - though note that some do (e.g. with remote diagnostics, supervising driverless vehicles in agriculture and mining), and this is likely to increase as Industry 4.0 and new platforms for work evolve.

In other words - the picture is more nuanced than this, and we want to avoid the misleading oversimplification that homeworking is a luxury for the better-off.

It is very interesting how many senior roles still seem to be advertised with a location attached to them - quite often a metropolitan area. There are more fundamental issues; should a local authority officer (for example) work remotely from the area that they are serving? Is emotional intelligence sufficient through skype or do people need to get to know one another through body language? What is the potential impact of home working on the housing market (£50k in London may appear good for some but quickly swallowed up in commuting and housing costs).

Stopping 'presenteeism' is a cultural change. The compulsory cost of living (housing, utilities, property tax, commuting) can at least reduce the commuting cost from homeworking but perhaps adds energy costs.