How do we make sense of how the crisis is changing the world as we are living through it?

Lots of conversations are taking place around how we track, learn from and make sense of the crisis, our response to it, and how we build bridges to a post-pandemic future.

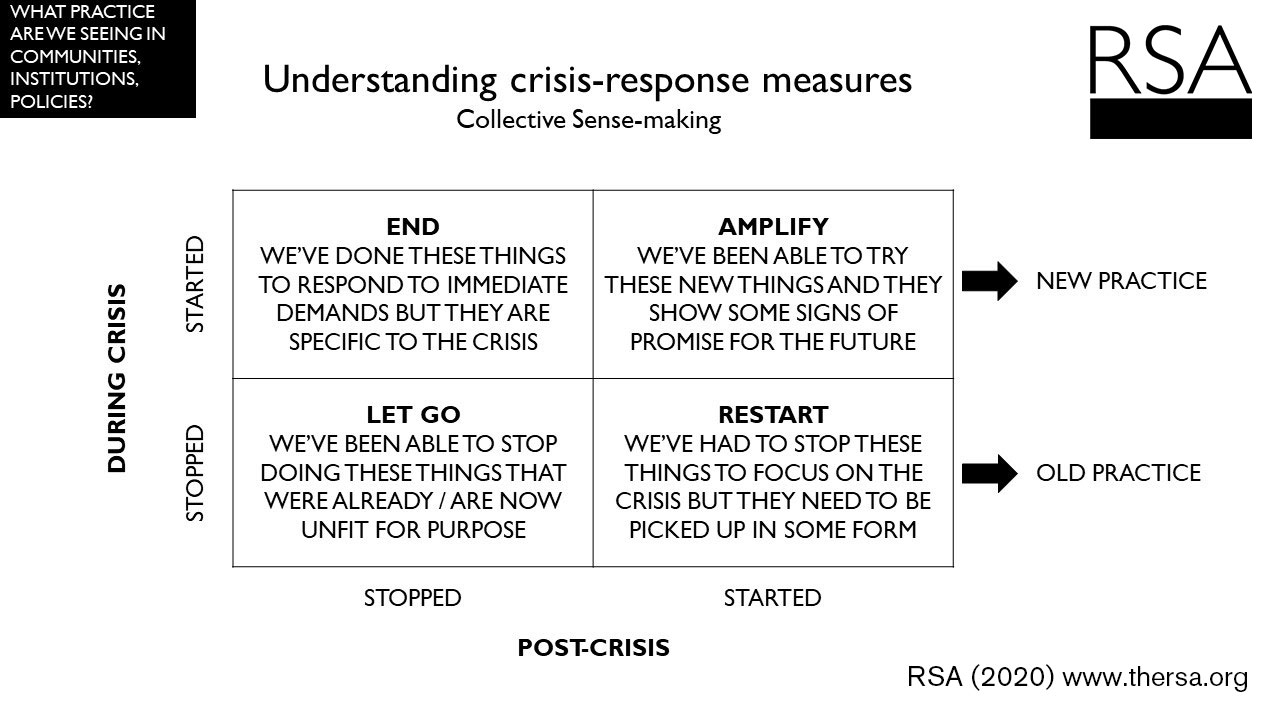

Thinking through the measures that we’ve all taken in response to Covid-19 in four categories - stopping activity, pausing activity, temporary measures, and new innovations – can help us focus on what’s worked and what can last.

4 types of responses to Covid-19

Our work at the RSA and our call to ‘think systemically, act entrepreneurially’ is grounded in an analysis about how change happens and why attempts at change often fail.

The current coronavirus crisis represents one such route to change, generating calls to ensure we ‘don’t let a crisis go to waste’. But this is easier said than done, of course.

Matthew Taylor has written about the different types of change and barriers that we may see arising in people, in our communities, our institutions and in terms of policy. To understand the impact of these changes many advocate for the deployment of a learning team alongside a crisis response team to learn what is happening as it is happening.

As we think of ‘bridges to the future’, we are thinking too of the variety of measures and activities that have been put in place during the crisis response, from those which may be most promising signs of new ways of doing things to those we see as only ever temporary.

Here’s one framing we’re working up that might help make sense of the crisis-response measures we are seeing:

Obsolete activity

The crisis has afforded us the ability to stop doing some things, either because we already knew they were not fit for purpose or because the crisis has rendered them obsolete.

We might look at the internal NHS market that has trusts competing against each other for scarce PPE, or the combative relationship fostered within local voluntary organisations by outdated commissioning approaches.

Post-crisis the challenge is to let go of these obsolete aspects of pre-existing systems - not only those things the crisis has rendered impotent but also those things we know are no longer fit for purpose.

As Peter Drucker said, the greatest danger in times of turbulence is not the turbulence, it is to act with yesterday’s logic. Graham Leicester describes this as the need to offer palliative care to old systems, which is a compelling way of expressing the challenge.

This has been historically difficult, particularly in the public sector, where new initiatives get layered on top of existing ones, compounding the problems. Yet letting go of what we no longer need releases trapped resources for work that is a better strategic fit.

Paused activity

We have had to temporarily stop doing other things in order to divert capacity to the crisis response, but we will inevitably have to start these back up again.

For example, we’ve seen a temporary halt to some routine cancer screenings, to dental appointments and a lifting of the duty to undertake adult social care needs assessments. Other activities that haven’t been officially stopped are obviously slowing down, for example the 50% drop in children’s social care referrals since the lockdown started. Collectively this drop in preventative measures is also storing up significant challenges for the future.

The core challenge in these areas post-crisis is to figure out how to restart these measures in ways that are sensitive to the changed context and are not simply a blind copy and paste of the pre-virus approach which just reinforcing old systems.

Temporary measures

Some things that we have had to do in response to the immediate demands of the crisis are inappropriate to become part of the new normal.

We’re seeing teacher assessments replace GCSE exams, for example, and police dispersing groups in public spaces - not something we necessarily want to see become a permanent feature of our society.

Ending temporary measures should be the most straightforward endeavour - there has been less time for them to become systematised, they are likely to be high cost (like the Government’s employee furlough scheme) and once the crisis demands fall the need for them will fall too.

We should do this in ways that maximise our learning transfer into other areas.

The dark side of this work is that there will be those who want to see some of the more authoritarian measures such as the intrusive surveillance of citizens become normalised and part of the mainstream.

Innovative measures

The opportunities opened up by the crisis for experimentation and change vary from significant increases in volunteering to the sudden increase in working from home. From online GP consultations to industries pivoting their business modelsn or simply finding new ways to do old things…

The crucial point here is that the crisis has cut through years of institutional and systemic inertia, presenting the imperative and the possibility for change.

More broadly, as one RSA Fellow said to me, there are too many changes that have happened because of the response to the virus which we shouldn’t lose. The post-crisis task is to find ways to amplify and embed the most promising changes and innovations.

Tilting the system towards positive change

We recognise the call to not let a crisis go to waste is more than a call to push through a particular agenda for change.

It’ also more than looking to simply experiment and scale successful innovations. The nature of system change is more nuanced than that.

There are at least four different approaches to handling the crisis response measures once we are past the worst: End, Amplify, Let Go, Restart. Taken together these seem to offer a more nuanced approach to post-crisis systems change than a simple ‘keep these/stop these’ assessment.

At first sight, the call to ‘let go of obsolete activity’ seems like the least important, but this warrants closer inspection. There are two ways we can meet the post-crisis need to amplify innovative practice and restart core activities.

One way is to unintentionally layer them on top of pre-existing systems which are unfit for purpose and thus maximise the likelihood that they won’t last. This approach also triggers the default resistance to change in which the status quo and those best served by it will react to prevent change.

The other way is to intentionally design new systems that will accommodate these innovations and new practice, as well as better serve those activities being restarted, and enable them to be co-ordinated and flourish. This is what we mean when we talk about the ability to scale. It is less about adoption, more about creating the enabling system conditions.

Last year we ran an ‘impact accelerator’ that sought to do just this. We brought together a group of a dozen innovators developing or growing solutions to the challenges posed by new forms of working.

Since then we have further refined our approach for system change in places and at scales that maximise the likelihood of innovations landing and ‘tilting the system’ towards positive change.

Some principles are emerging from this work and our wider engagement. We are seeing the value of:

- bringing in fresh information and perspectives so that social innovators can openly and honestly reflect on whether the business or organisation they are growing are likely to achieve to the impacts that first inspired them to act.

- fostering a sense of collective endeavour, a group willing to give time and energy to support and challenge each other and potentially develop formal collaborations.

- connecting this group to the architects and guardians of the wider system in which the innovators are operating. By doing this the innovators can see the reasons for a system’s immunity to change and develop strategies and alliances which maximise the chance of their innovations achieving transformational change.

If we want change to happen, we need to think about how we want that change to happen, not just the future we want to see. That’s what we’re working on at the RSA.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

Interesting item and particularly the framework/matrix for evaluating options. We have discovered that there are services and products we can do without or buy less of. This is painful to recognise for the business owner but a useful outcome as excess consumption will lead to increased carbon emissions. How can we help such businesses with their evident skills and entrepreneurial experience move to new productive, less carbon intensive outlets? So here there is some LET GO and some redirect (RESTART). Related to this are the fossil fuel industries, whether extraction or dependent businesses. There is understandable antagonism towards them. This is damaging because it triggers defensive behaviours. The better question is, given we should STOP this type of business, how to take/develop/incentivise those skills to Greener/Zero-Carbon ways of production, a sort of RESTART.

The year 2020 has been a rollercoaster ride for all of us, it has taken a huge toll on us, physically and mentally. It is not just the virus, there are a lot of other events like fires, protests, etc which have shaken the world and its people. Hopefully, once this whole pandemic situation ends we come out if it with a better perspective about life and being more grateful about it.

Alison I would be interested to learn more about your work with Boards using the tool, I have a similar idea. Penelope I understand the constraint of public sector commissioning which doesn't always spend money in the right way and emergency response being carefully focussed and changing in response to local intelligence providing relevant and more cost effective services. There is a missing part of this conversation about the unequal impact of CORVID19 on Black and Minority Ethnic people who were 5 times more likely to die and pulling out and looking at the learning. The tool would be useful for discussions about how to achieve equity as the current systems to address inequality are costly to th public purse and the people losing their lives. I would be interested in being supported as a Fellow to do a project using this tool taking health inequalities as a social movement to another stage.

To me I'm sorry to say this whole discussion is just too intellectual. You are not facing up to the realities of the situation this country now finds itself in but are acting as elite observers. The country is facing the most enormous debt mountain. We will not be able to afford many of the trappings and quality of life we have come to expect and rely on. Many service sector jobs have been shown to be completely unnecessary and untenable. We are educating 000s of students in higher education for careers that rely on what I call the surplus cash of society- the nice to haves. But there is no surplus cash. Funding the NHS relies on an economy that is efficient and creates wealth. But thousands of our businesses will not be generating profits for some considerable time. Even the financial sector has quickly come to realise its whole modus operandi of cramming people into Canary Wharf towers is untenable and no longer needed. Making changes to the way teachers teach, offices function, factories operate, care homes offer protection etc all have inherent costs. I hear no practical ideas on how we create wealth, and jobs that have real purpose and practical social value.

As schools, nurseries and other education providers seek to unravel the guidance around introducing safety measures and offering on-site education to a growing number of students the bigger question of what kind of education system do we really want is being asked in many quarters. This article expresses and clarifies some of what has been rattling in my brain. As Alison has noted, the matrix is proving useful with many. Thank you.