People, businesses and communities need certainty so we can make plans and be as proactive as it is possible to be. For this, the government should announce a ‘year of stabilisation’ whilst it engages widely to consider the longer-term structural change that is required post-Covid-19.

Since just before lockdown the RSA has focussed its work on the ideas of Building Bridges to the Future; asking how responses to Covid-19 might prefigure a better future when the pandemic has passed. Even in an appalling crisis, are there opportunities that are emerging for positive change?

The current implicit policy assumption is that through a carefully managed, but inevitably partly experimental, process we can gradually reduce constraints on normal activity, while reserving the capacity to tighten up if indicators – particularly the R-number – start to deteriorate. The attraction of this way of thinking and acting is that it is both hopeful –assuming things can get incrementally better – and also reasonably agile in terms of adapting to social behaviours and the epidemiological situation. There are however several problems.

- First, a strategy of continuous loosening, with the ever-present possibility of a reversion to tighter control maintains high levels of uncertainty. We need organisations to think creatively, responsibly and ambitiously about operating differently, but economic evidence shows that uncertainty is itself an inhibitor of investment and consumption. It inhibits not just consumption but innovation and investment in transitional solutions.

- Secondly, the idea of an incremental loosening has a self-defeating psychological effect. Evidence from parts of America that have loosened up suggest that once social spaces have re-opened and people have started to socialise, folk are likely to become progressively less careful. We are seeing this in parts of London already.

- Thirdly, as we are seeing with the proposed re-opening of schools, the politics associated with the day-to-day reassessment of the level of restriction is problematic. There has been a broad tendency of the left to be precautionary and of the right to favour rapid renormalisation, which unnecessarily politicises debate at a time when unity and trust are important public goods. We need to try to find some balance of responses acknowledging the validity of each perspective.

There is an alternative approach. The Government could undertake rapid policy development and public engagement leading to the establishment of the framework for the year of stabilisation. Obviously, there would have to be parameters, but the policy could be to maintain transitional arrangements for a year unless the virus was effectively conquered, or the R rate went over 1.0. This might enable people to adjust and plan. It is noteworthy that – in an attempt to plan – some organisations including large businesses and universities have already told their employees that they should assume social distancing will last until next spring.

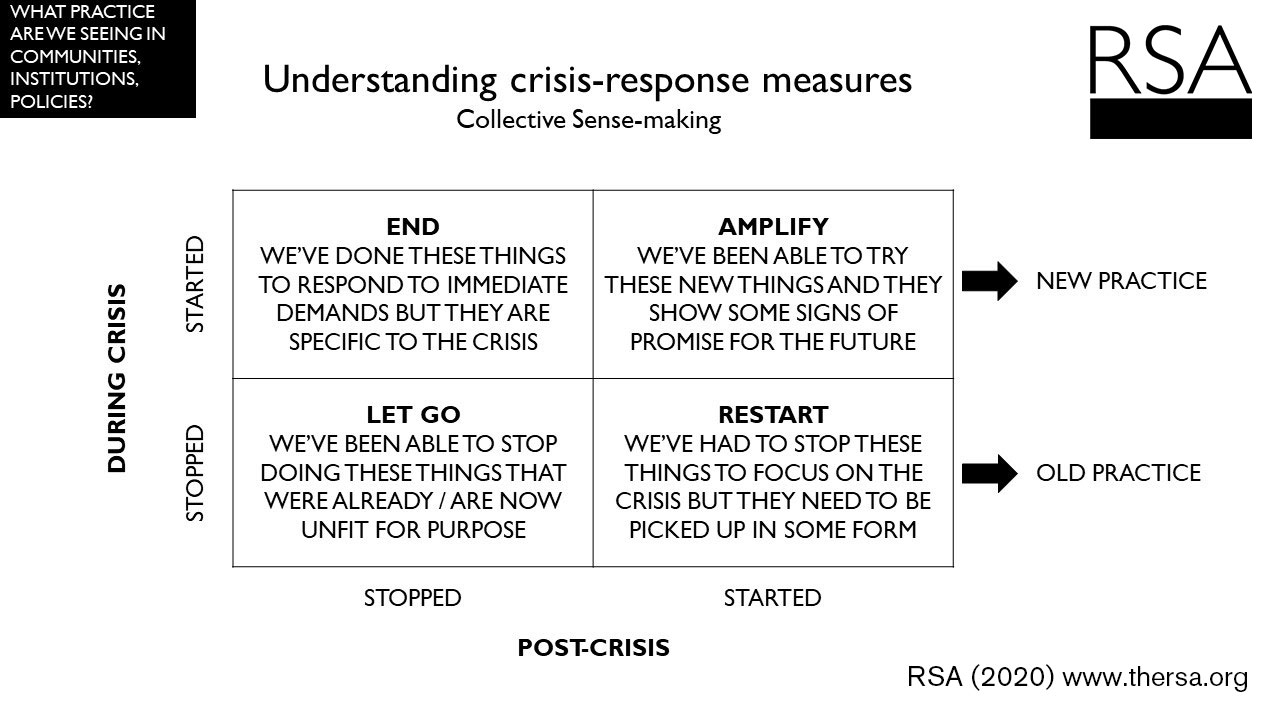

Rather than seeing adaption as merely a crisis-response, we could test the resilience and popularity of policies and innovations that might then be adapted to a post Covid-19 future. A key design consideration for the transition should be that the arrangements have the potential to last much longer than a year, either because the situation with the virus does not change or because the experiment has revealed the scope and desire to do things differently for the long term. This lies at the heart of the experimental model of change - from Covid-19 response to a bridge to an alternative future - outlined by our colleague, Ian Burbidge.

3 Principles and 10 ideas for transition

Any ‘stabilisation year’ measures should be grounded in three principles.

- They should be direct, i.e. resources and support should get through to where they are needed.

- This means that we should favour approaches that are comprehensive and universal, rather than hyper-targeted.

- They should create short-term capacity and resilience that can be built upon beyond the year of stabilisation.

With this is mind, here are 10 ideas for a medium-term transition.

1. Get people back to work and distribute work fairly

Emerging from lock down we face a lack of underlying demand for labour which, as Adair Turner argued at a recent RSA event, could be exacerbated by accelerated automation.

Tax incentives (for example, National Insurance being temporarily reversed into an incentive rather than a charge on employers) are needed to encourage employers to take on more people.

A six-day week (potentially including schools) based around two three-day shifts could be introduced to ensure more people can work as the economy adjusts.

Also, having ‘A’ and ‘B’ teams (as they do in South Korea) with deep cleans at the transition point can help manage the spread of the disease in workplaces and would complement track and trace.

2. Support workers and reduce insecurity

We need to continue to provide additional support to individuals directly, especially those on lower incomes.

In due course, resources could be shifted from the furlough and self-employment support schemes, as they are inevitably wound down, towards supplementing the salaries of workers now restricted to 60% of conventional working hours.

This could be done through the establishment of a trial universal basic income (UBI) or Negative Income Tax giving regular cash support to all workers.

One option the Government might wish to consider is focusing this support on those with incomes below the higher tax threshold. Key workers who cannot reduce their hours should be given an additional flat rate payment by way of gratitude and compensation.

3. Help workers develop new skills and opportunities

With a three-day working week, many people would have some additional free time. This is an opportunity for a vitally necessary step change in adult learning.

Through the provision of free or subsidised courses and structured volunteering opportunities, millions of people could use the transition to explore and to develop new skills.

Scaling up digital accreditation (for example, the badges being used as part of the RSA Cities of Learning pilot) would enable highly flexible and practical forms of learning.

A Good Work Fund could be launched in the form of subsidies for work that fulfils certain criteria: a real living wage, training attached, and green focused where possible.

As a group of work-focused organisations proposed this week, a job guarantee for longer term unemployed is also needed but compulsion should not form part of the toolkit enabling Job Centres to reclaim trust as a supportive institution. A training or work guarantee for 18-to-24 year olds will be needed as this group is likely to be hit particularly hard.

4. An asset policy to increase resilience and fairness and get the economy moving

Inequality of wealth and assets is greater than that of income and there is danger that monetary policy and growing indebtedness could further exacerbate matters.

An asset strategy would, on the one hand, give low-risk, no interest loans to poorer citizens enabling them to avoid debt and invest in training or setting up a business.

On the other hand, it could create carrot and stick incentives for those who are asset-rich through money tied up in homes, pensions or savings to dip into those assets, either investing them in social, environmental and cultural projects or simply increasing consumption.

Local authorities, LEPs and financial institutions such as community banks and credit unions should receive government support to match pooled public, private and philanthropic resources in support of individuals at risk of indebtedness, small businesses and the voluntary and community sector. These pooled assets should work together to form an active local network of support blending grants, low-interest flexible loans, and, in the case of business, equity.

5. End the digital learning divide

One of the positive outcomes of the crisis has been a rapid levelling up of good digital practice in many sectors. This can continue and should boost productivity.

However, as more services are online it becomes even more vital to ensure that no one is excluded in terms of equipment, network access or skills. This is particularly vital and urgent when it comes to the digital learning offer for children and young people in training. Every child and college learner should have access to a ‘home learning check-up’.

Where the home learning environment cannot meet required standards then alternative arrangements in vacant offices, libraries and community centres should be made available, with safeguarding robustly in place.

A remote volunteer tutor force should be recruited from graduates and occupations in relevant fields, trained in learning materials and curriculum and made available through schools and colleges to support increased learning capacity and lifting some of the burden from teachers (not least as many may be isolated or shielded).

6. Make volunteering a universal expectation

An extended transition is an opportunity to work with public services, charities, business and the community sector to embed volunteering in the processes and structures of everyday life.

The scale of volunteering we have seen over the past weeks can be captured and developed. This could be crucial part of a programme to improve and green the public sphere. Or, through a combination of scaling up schemes like Shared Lives and a social care volunteering initiative, perhaps we could reduce the need for residential provision and make that provision more humane.

There are heavy caveats here. Much of the voluntary sector – including its volunteer managers - has been decimated in recent weeks, and there will need to be frank assessment of the damage done and the remedies needed to rebuild.

A longer term Commission on the rebuilding of the voluntary sector post-Covid19 is needed to build on the Civil Society Futures Inquiry of 2018 if we are to realise this goal.

Key civil society and governmental actors must learn lessons from the mismatch between volunteer enthusiasm and demand for volunteers amidst Covid-19 as institutional capacity to manage the volunteer effort has been hampered by a failure to provide additional support.

Where there is capacity to absorb volunteers, especially in care arenas, that should be actively supported. A volunteering commitment could also be encouraged for those who receive basic income.

7. A green, levelling up, transition

In line with the UK’s net zero target, emergency public investment in job creation (and structured volunteering) should be focused on key green priorities. One obvious candidate is home retrofitting.

There would be several benefits of centrally funded retrofit programme delivered through local public, private and civic partnerships. Retrofitting helps those, especially those on lower incomes, for whom fuel bills are a large part of their outgoings.

Too often action after economic crisis exacerbates spatial inequalities but homes needs retrofitting as much in Scunthorpe and Cornwall as much as those in city centres and the South East.

A resilience fund, advocated in the policy briefing launched this week by our colleague Josie Warden, could also support burgeoning circular economy innovation within clothing and textiles, food and other sectors (including medical supplies) to enable greater regional resilience, to stimulate local demand (including form major local buyers such as hospitals, universities, colleges and local authorities) and create high skilled local employment.

8. Safe and clean local transport

The RSA’s polling shows how much people have valued cleaner air, less noise and congestion during lock down. During transition employers could assist with social distancing by staggering opening/office hours ranging from 7.30 to 14.30 to 10.30 to 18.30.

Local authorities should follow the lead of London and Greater Manchester and reconfigure road space to make life easier for walkers, runners and cyclists. A major expansion in electric vehicle charging points could be another opportunity for green investment and job creation. This move could be supported by much more generous tax reliefs and even vouchers to support the purchase of bikes and electric vehicles.

9. Opening up the hospitality economy safely

Strictly dependent on essential public health requirements and infection prevalence, pubs, restaurants, theatres and so on should be allowed to re-open on condition that have had proper staff consultation, a safe workplace audit (perhaps from the already expanded Health and Safety Executive) and employ a trained Social Distance Officer (which would be an opportunity to upskill our huge private security workforce).

All visits to these leisure sites could be pre-booked in time-limited slots, perhaps with an advisory limit of two activities per week (a booking system would also assist with track and trace). Where rents are becoming impossible to service, local authorities should be given the freedom, support and powers to take over freeholds to protect local jobs, business and community life.

10. Reforming governance including through digital democracy

Alongside stabilisation policies, profound changes to how government engages with expertise, representative interests such as business and the trade unions, with other levels of administration and the public are required. These cannot wait as they lie behind multiple failings in the Covid-19 response which, in the UK and many other contexts, has been fundamentally a failure of governance.

Henceforth, governance should be open, transparent and engaged embodied through:

- All scientific evidence should be open-sourced and available as decisions are taken shared with the expert research community. Scientific advisory committees such as SAGE should take account of wider inputs into its advice to Ministers.

- Multi-layered governance should be introduced as a formal part of ministerial decision-making as appropriate. This architecture should include, local and sub-national government, the unions, business, and voluntary and civil society. Advice from these committees should be published within 24 hours.

- Modelled on the Climate Assembly commissioned by six Select Committees and reporting soon, a series of post-Covid-19 people’s assemblies should be convened online as ‘mini-publics’ to help set the principles and policies on which the future social contract, housing and access to space, public services including health and care, education, and climate response. There could be local versions of these assemblies as communities look to reflect, rebuild and build upon the many positive aspects of the past few weeks such as the obvious willingness to look out for one another.

The Covid-19 response has shown the severe limitations of the interaction of political decision-making and small groups of experts. A lack of trust in this process has enabled false information and politicised research to gain traction.

The traditional Beveridge or Royal Commission model of public administration is too limited in our world. Our response should both involve more experts but with open and transparent information flows and more public involvement but in well-designed and curated deliberative democratic processes.

Plans for the post-war era were not put together in a hurry. They were thought through over time within government, led by experts ready for a post-war transformation. Public engagement was via the 1945 election, which resoundingly voted for transformation. The need now is for a 21st century version, in a less deferential age, of forging a consensus around a more resilient social contract.

Developing a transition plan like this even in a highly constrained time frame, is an opportunity to prefigure a more open, participative from of policy making. The immediate crisis may have past – for now – but we are a long way from returning to any kind of normal. While we think through the world we want to live in and the adaptation we have anyway to make to respond to the climate emergency why don’t we use this time to work together; a year of stabilisation to build a bridge to the future.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

This Pandemic has raised the vital question to societies about having an economic awareness of where they are and where they are going respectively. Historically, it can be observed that a Pandemic ensues due to a large unawareness of the affected community. Here, whilst each such society can exist in oblivion of 'not-knowing' to a certain extent, such self-induced oblivion can be a major reason for conception of such diseases societally.

As we come out of this Pandemic regressionally, it is important overall that each affected society meets the previous and enacted oblivion with full responsibility. This would include taking major steps to understand the medical, biological and psychological causes and formations of such Diseases. Each country needs to budget and plan for developing capabilities that would meet and mitigate such risk prior to it eventuating. So, there some really big projects including computerisation, medical research and international collaboration that needs to be undertaken.

Secondly, a moral strategy of 'Dont Know - Will Care' has to be adopted incrementally as we come out of this Pandemic. So, places and touch-points that are considerable for Health assurances, including mental well-being, should be acertained to be acceptable and not posing any such Risks. There should be a committee or assessor appointed by the Laws of each country that would undertake such responsibility. In such a 'Dont Know - Will Care' approach, each economic artifact has to be defined, assessed and passed to be compliant with the adopted restart mechanisms.

Coronavirus, however awful in so many respects, has a jewel in its crown: an enormous opportunity to get rid of those things which do real damage to our country, society and way of life:

Insist that local councils raise business rates to such extortionate levels as to drive these out of town – forever:

All quasi American Fast Food Outlets – KFC; Five Guys; McDonald’s; Burger King.; et alia

Coffee Houses: Costa, Café Nero, Starbucks.

Pull down the Festival Hall and get a proper, classical hall put there on the most important site in the world.

Scrap HS2 and repair/renew/extend the rail infrastructure we currently use perfectly well.

Stop the obsession with cycle lanes and, instead, fill in the potholes which pose a much greater risk to cyclists.

Repaint the white lines on roads and restore millions of missing cats’ eyes.

Repaint the white lines on pedestrian crossings rendering them visible to the motorist.

Abolish Inheritance Tax as it is no more than triple taxation at least, goes against the basic principle of fair taxation and is, in essence, theft.

Encourage and support competition for Stagecoach

Scrap the House of Lords.

Move the Commons to Bradford.

That’s for starters…..

As a teacher, I like the 6 day, A/B idea. As a parent, I have noticed one positive effect of lockdown schooling: more sleep in the morning means that my children seem far less tired even though they are still working hard. That may be another "bridge to the future": the timings of the school day in general.

Urgently needed analysis and, without doubt, the most intelligent proposals and forward thinking I have yet to see regarding our uncertain future, over which many are still in denial. Extremely difficult and bold options but surely necessary. Well done.