RSA Foresight Lead, Fabian Wallace-Stephens, introduces our report on the rural and post-industrial perspectives on the just transition in Scotland and highlights some of the key takeaways which, if implemented, will help achieve this vision.

Involving a diverse range of citizens in the exploration and shaping of better futures is one aim of participatory futures. Further, employing participatory futures can help integrate lived experience into decision-making. This can in turn help build legitimacy in policy- and decision-making, by highlighting the voice of communities most impacted by change.

During the summer of 2022, we hosted two participatory futures workshops in Dumfries and Fife investigating how shifts in the energy system could impact regions like these and convene citizens to collectively imagine different possible, and better, futures. The research, in partnership with the Scottish Government, emphasises novel insights on how net zero could impact rural and post-industrial communities. It also proposes pragmatic recommendations for bringing communities into the just transition planning process.

Read the Rural and post-industrial perspectives on the just transition report below.

Rural and post-industrial perspectives on the just transition

Read our key findings and recommendations for how to involve communities in just transition planning.

Just transition: reinventing places and creating green jobs

Green job creation is often highlighted as a huge net zero opportunity. For example, the UK government announced in May 2022 that it will aim to support the delivery of 480,000 skilled, well-paid green jobs by 2030. However, when we spoke to communities about renewable energy projects in their local area, they expressed scepticism over the extent to which they expect to benefit. In Fife, for example, citizens suggested that previous high-profile projects such as the use of the Levenmouth Demonstration Turbine by Samsung have had limited impact in terms of local job creation.

Several studies suggest green job gains will be more geographically dispersed (chapter 10 of the European Investment Bank’s Invest Report 2020/2021 provides interesting context) than those in industries like fossil fuel extraction, car manufacturing and heavy industries. A previous RSA policy briefing - Decarbonisation dynamics: Mapping the UK transition to net zero - explored how this could impact different local areas across the UK. A consequence is that alongside supporting new green jobs growth, places once reliant on emissions-intensive industries may need to find other ways of reinventing themselves. The Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations (IDDRI) suggested in its Lessons from previous 'coal transitions' report that there is no one size fits all approach, but economic development pathways can involve strengthening local entrepreneurial networks or soft attractiveness factors for tourism.

The communities we engaged with were a wellspring of ideas for positive change in this respect. In post-industrial Fife, the restoration of the River Leven was a focused point of discussion, as participants felt that it could create opportunities for leisure and tourism. Participants hoped that this could be realised through community-led projects, like the tidal-powered Levenmouth Whale Project, which brings together art, engineering, and eco-tourism to create a unique attraction for visitors. While in rural Dumfries, where many workers are employed in agriculture, participants highlighted a unique opportunity to develop local circular supply chains to reuse sheep wool for insulating homes.

Regenerative futures, lifestyles, and values for communities

A regenerative mindset recognises the interconnectedness of humans, other living beings and ecosystems, which rely on one another; and that restoring and rebalancing these relationships is critical to address the social and environmental challenges we face. One way we introduced this lens into our workshops was to ask participants to think about the impacts of technologies and societal changes relevant to net zero from the perspectives of local wildlife and natural landscapes including the Scottish wildcat and River Leven – perspectives that are often missing from discussions around a just transition and other policy debates.

Representing the wildcat, (and in relation to our homes when discussing responsible heating), in my case, a better climate will mean fewer droughts, a safer home for us.

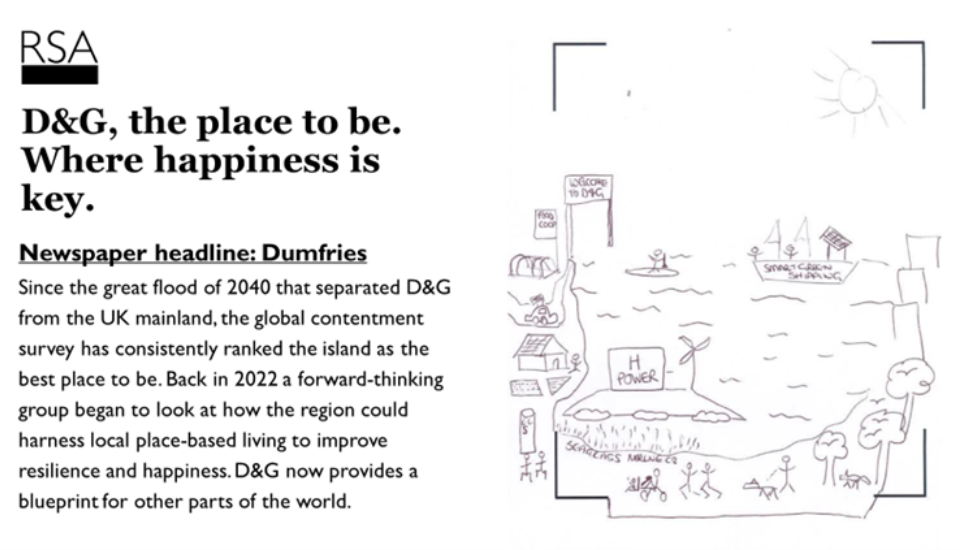

This activity helped participants consider the nested, natural, and social systems in which their community is situated. This was also reflected in outputs of our creative visioning activity, which was inspired by The Thing From The Future and asked participants to produce speculative newspaper headlines, postcards, and objects from a desirable future. Several of the artefacts that were developed pointed to an awareness of the need for more regenerative ways of producing and consuming, and wider lifestyle shifts. This included one newspaper headline imagining a future where consumer products (eg TVs) are produced locally using recycled materials and another detailing the spread of eco-developments that combine sustainable buildings and green spaces with shared community living. A third artefact, a postcard from the future, titled Utopia by its author, depicted a self-sustaining community in Fife that does 'no harm to the environment, the animals or each other.'

Scotland’s future may be solarpunk

Participants were particularly interested in smaller-scale forms of renewable energy production (eg individual wind turbines and solar panels), and business models that provide communities with direct financial compensation for exporting renewable electricity to the grid. Several artefacts developed during the visioning activity depicted community-owned and controlled renewable energy projects.

Solarpunk is a literary and artistic movement that offers speculative visions of more regenerative futures, where clean technologies have been developed in harmony with the natural environment and the needs of local communities. The movement encapsulates a do-it-yourself ethos and explores alternative economic models. Recent examples include Black Panther’s Wakanda and the animated Disney film Strange World.

Having read Kim Stanley Robinson’s solarpunk novel New York 2140, which imagines a future where sea levels have risen by 50ft, and many parts of the city are underwater, but communities have adapted, I was particularly struck by one artefact developed by a participant in Dumfries. A newspaper headline depicting the region as a physical island after the ‘great floods of 2040’ separated it from the mainland. However, in this fictional version of Dumfries, the region is now marked as a top scorer in global contentment surveys and provides a blueprint for other parts of the world, as communities have learnt to harness local place-based living to improve resilience and happiness.

New York 2140 explores similar themes as the city continues to flourish as a sort of “Super Venice” with the parts of the city such as Lower Manhattan that are partially submerged becoming hotbeds of social innovation, creativity and experimentation while communities are supported through a growth in cooperatives and mutuals.

Just transition planning and the role of participatory futures

These visions can help in understanding how both day-to-day life and wider systems could look in a future where a just transition has been achieved. This is a crucial starting point in understanding what exactly needs to change in terms of policies, behaviours, and systems to realise a just transition. They provide a holistic representation of the future, depicting worlds that bring together new technologies, changes to the natural environment and to ways of living. This is in line with research that suggests participatory futures are ‘unencumbered by policy silos and connect the importance of multiple sectors collaborating to the addressing of local needs'.

Across our engagement, we found that communities have a clear desire to be more involved in decision-making and practical action related to the just transition but feel a lack of agency at present. However, these approaches can also help build people’s imaginative capacity and give them a greater sense of agency and optimism about the future. According to our evaluation survey, 61% of participants agreed that they felt more able to imagine a future energy system and 67% felt more able to create change as part of their community.

In our report, we put forward a series of recommendations to for how to do effective community engagement that leverages participatory futures approaches, based on learnings from the design, delivery, and evaluation of our workshops. Some of these recommendations relate to working more closely in partnership with community organisations to tap into local networks and scaling wide-reaching community engagement activities outside of formal workshop contexts. While in Fife we worked in partnership with the local council to attract a diverse range of citizens, in Dumfries we held pop-up engagements at Dumfries Agricultural Show to gather the views of ‘unusual suspects’ including farmers surveying agricultural machinery and the owner of an alpaca farm.

Other recommendations relate to how to better design and evaluation participatory futures activities. This can involve experimenting with creative approaches such as immersive experiences and serious games. But our experience also suggests a need to build more time for ongoing and sustained engagement with communities. Lastly, while impact evaluation in the participatory futures field is still nascent, there is an opportunity to work with others to define shared frameworks and approaches here.

Meaningful participation is critical in the context of the just transition, and we hope that going forward, the approaches demonstrated in our workshops will provide a model for community voice in decision-making that can be replicated across Scotland and other parts of the world. And, by sharing these practice learnings, we hope that RSA Fellows and other changemakers consider using participatory futures in their work.

Thinking about the climate crisis and the challenges it represents, are you optimistic about the future? Let us know why in the comments section below.

Related articles

-

Rural and post-industrial perspectives on the just transition

Report

Fabian Wallace-Stephens Emma Morgante Veronica Mrvcic

This report explores how changes to the energy system could impact specific Scottish regions and bring together citizens to collectively imagine better futures.

-

A regenerative design approach to shaping a just transition in Scotland

Blog

Nat Ortiz

Regenerative design is an approach that sits at the heart of everything we do. Read more about the practice and its application in our Just Transition for Scotland project.

-

Empowering citizens to shape a just transition for Scotland

Blog

Fabian Wallace-Stephens

We're hosting a series of participatory futures workshops over summer 2022. Join us to explore how changes to the energy system could bring citizens together to collectively imagine better futures.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.