Earlier this week The Times newspaper published a letter, signed by representatives of 60 organisations committed to expanding the life chances disadvantaged children, making clear their opposition to the government’s plan to overturn the ban on new grammar schools. I was more than happy to add my name, and that of the RSA, to the letter. This is why.

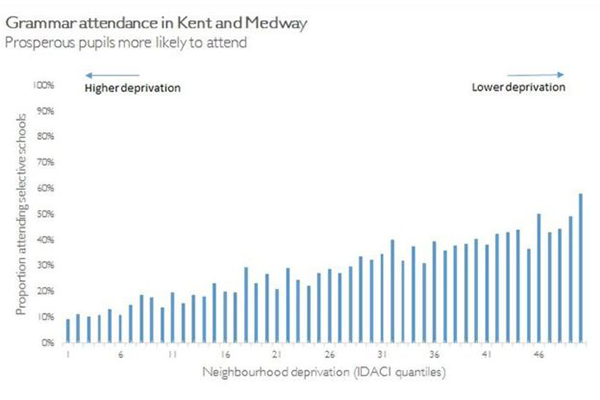

As others have not only claimed but proven, grammar schools simply don’t do what their supporters claim they do – act as an engine of social mobility, allowing bright but poor kids to reach their full potential, boosting England’s educational performance in the process. That is because, as the BBC’s Chris Cook has demonstrated, grammar schools simply don’t teach very many bright but poor kids, having long since been colonised by the sharp-elbowed middle classes. As the table below shows, in Kent and Medway (a selective education authority) a young person living in the poorest neighbourhood in county has a less than 10 per cent chance of attending a grammar school, while someone living in the wealthiest neighbourhood has a more than 50 per cent chance of doing so. Why? Because not only has 60 per cent of the attainment gap between rich and poor pupils already opened up by the age of 11 when the entrance exam is taken (making it far less likely that poor kids will pass it), but the system is further skewed in favour of the rich by the fact that the entrance exam – notionally a test of intelligence rather than knowledge – can be gamed, so long as you can afford the private tuition designed and explicitly marketed for that purpose.

Kent and Medway is much discussed because the county hosts such a large number of grammar schools. But have opponents of selection seized on it because it supports their case in a way that a broader, country-wide analysis might not? No. Across England, 13.2 per cent of secondary school pupils are poor enough to be eligible for free school meals (FSM), compared to just 2.5 per cent of grammar school pupils. This cannot be explained solely by the fact that FSM pupils are, on average, well behind non-FSM pupils by the time the 11+ exam has to be sat. As the Education Policy Institute has shown, 6 per cent of high attaining pupils at the end of primary school (the highest attaining 25 per cent) are eligible for free school meals, yet the number of FSM pupils in selective schools is less than half this – a gap that gives some indication of the size of the ‘tutor effect’, among other factors. Nor can the social exclusivity of grammar schools be explained away by some quirk of geography – the possibility, however remote, that bright but poor pupils live too far away from these schools to attend them. Pupils eligible for free school meals make up 6.9 per cent of the high-attaining group living within travelling distance of a selective school – higher than the proportion of high attaining kids who are eligible for free meals across the country as a whole. As wealthier children travel significant distances (twice as far on average) to attend grammars, bright but poor local children remain shut out.

The tragedy, for all those highly able but poor pupils living near to a grammar that they do not attend, is that the very existence of a selective school in an area does real damage to the educational prospects of students in non-selective schools nearby. In non-selective local authority areas 57 per cent of pupils achieve five A*-C GCSEs including English and maths. In selective authorities that figure drops to 47 per cent. The impact on FSM pupils of going to a non-selective school in a selective area (a de facto ‘secondary modern’) compared to a non-selective school in a non-selective area (a comprehensive school) is also stark. In the former, only 27 per cent of FSM pupils get their five good GCSEs including English and maths, compared to 35 per cent in the latter.

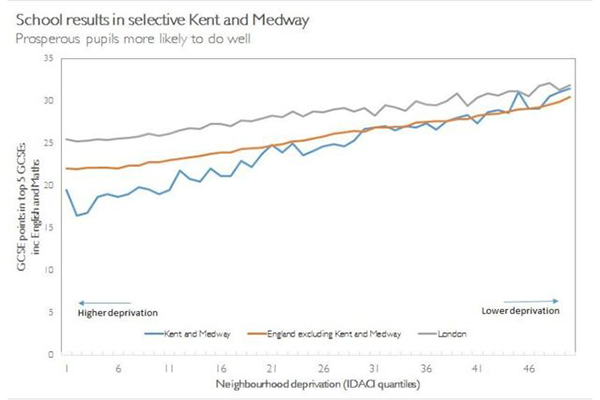

The consequence, unsurprisingly, is greater inequality, with grammar schools almost guaranteeing high attainment for the relatively wealthy minority who attend them (97 per cent of grammar school pupils achieve 5 A*-C GCSEs including English and maths), while damaging the performance of the poorer majority who do not. If we return to Kent and Medway, we can see that all but the very least deprived pupils do worse than elsewhere in England, resulting in a lower aggregate performance for the county as a whole.

But the most interesting comparison – and the one that most frustrates those who have been working so hard over recent years to drive up the quality of comprehensive education – is with London, where performance in non-selective schools has rocketed to such a degree that people are now flying in to the capital from around the world to find out how it was achieved.

The fact that the grey line never drops below the blue line, and that it rises more gently, tells us that it is possible to build a non-selective education system that raises standards for all; a more equal system which benefits the poor while doing no worse for the rich.

Which brings us back to the Educational Policy Institute’s key finding: that in terms of the progress that pupils make while at school, high quality non-selective schools (the top 25 per cent by value added) are outperforming grammar schools, doing so at scale (there are five times more high quality non-selective schools as there are grammars) and doing it for everyone (12.6 per cent of their pupils are eligible for free school meals versus 13.2 per cent nationally and 2.5 per cent in grammars).

Little surprise then that researchers at the London School of Economics found that the early academy schools that powered so much of the increase in London’s educational outcomes over the last decade and a half, are the real engines of social mobility, educating 50,000 FSM-eligible pupils compared to the 4,000 in grammars, adding real value (a full grade per pupil across five GCSEs) and transforming life chances (increasing the number of pupils going on to university by a third).

Anyway, enough numbers.

The real point here is not that grammar schools aren’t good schools. Or indeed that we should disapprove of a parent’s decision to send their children to a grammar school. On the contrary, a parent’s first responsibility is to do the best they can by their own children and a grammar education is as close to a guarantee of success as can be found in the state sector.

Rather, it is that this is a classic case of the private and public interest colliding. From a system perspective (which is, of course, the Prime Minister’s first responsibility), the evidence is clear: grammar schools do more harm than good. Researchers have found no evidence of any positive impact on attainment by grammars that isn’t explained by the relative wealth and high prior attainment of their pupils. But they have found plenty of evidence of them doing very real damage to the performance and prospects of non-grammar school pupils in the area where they are located. That’s a lot of losers for a small number of winners whose needs would be met just as well by the best comprehensive schools.

That is why the coalition of organisations to which I added the RSA’s name is so wide – spanning the political spectrum and encompassing academics and teachers, charities and professional bodies. There is much about education policy that will continue to divide us. But on the importance of not returning to a system that pushes children down two different life-altering paths at the age of 11, we all agree: that is not how you build “a country that works for everyone”.

Related articles

-

What role can schools play in developing young people’s social agency?

Hannah Breeze

"Social action as a means of developing and expressing character might just be the antidote to the ‘education by numbers’ system", argues Hannah Breeze from the RSA Academies team.

-

Education versus poverty

Julian Astle

Do we distribute the education budget in a way that is likely to help children overcome the many barriers poverty places in their way?

-

Student voice: how New York schools are tackling social injustice

Naomi Bath

Naomi Bath reflects on a recent trip to New York visiting schools, sketching out different ways in which students are using their voice to tackle social injustice.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

I think it would be worth asking what is it about a grammar school the parents want for their children. What is it about a private school, parents are prepared to pay for?

Is it the fancy uniform, smaller classes, children of similar ability , behaviour, playing fields, extra curricular activities, better teachers etc. Taken item by item it does not seem impossible to meet these needs on the state comprehensive system.

I do feel MPs, and others who influence the education debate should put their children in schools they think fit for other people's children. It will concentrate the mind no end.

I would like to re-cast the whole debate into a discussion about the advantages of 'SETTING' over 'STREAMING'.

I am an Oxford-university educated product of a grammar school and son of educated middle-class parents who could not have afforded a private school. (I also had to work to pay most of my maintenance costs at university). I don't feel unduly guilty about my educational opportunities and I would certainly not want my grammar school closed down or converted to a comprehensive.

But I don't think we should create any more schools which 'brand' children at the age of 11 and reduce their opportunities from then on. Grammar schools are effectively examples of 'streaming'. Streaming is a system in which pupils are labelled in accordance to the average of their abilities in each subject and then taught right across the curriculum with all the pupils of a similar average. This is utterly disheartening and militates against educational aspiration and social mobility.

Even in a selective grammar school I found that in the subjects I was good at I suffered the frustration and boredom of 'mixed ability' teaching. Having read several Shakespeare tragedies and being able to compare and contrast them, it was a teeth-grinding experience to share a lesson with someone who could barely understand or read out a single soliloquy, and a nerve-wracking experience for that fellow pupil to be bewildered by a textual analysis discussion. The one subject which was 'set' was Maths. I and all those much more mathematically gifted fellow students were profoundly grateful that we were taught in different sets.

Everyone accepts and understands the promotion and relegation of sports teams. Comprehensive schools should adopt the same approach for every single subject on the school curriculum. Some pupils will be in the top football, gymnastics and art sets, in middling sets for History and Geography, and maybe in lower sets for Maths and Science....and of course other pupils will have a completely different 'profile' of sets. The setting arrangements before the first year will have to be determined on the basis of some tests. Thereafter, an end of year test will determine which 5 pupils are promoted to the next set and relegated to the one below. This system avoids branding anyone as 'grammar' or 'secondary modern', gives scope for aspiration and allows the flexibility to respond to the different rates at which children develop: physically, mentally and emotionally.

So I am in favour of mixed ability, non-selective SCHOOLS but competitive and selective EDUCATION.

Marek Effendowicz

PS. I am at the moment most days in the John Adam Street library - anyone who would like to have a chat in the Gerrard Bar about this issue (or any other) please get in touch.

I have left a general comment on this board , bit late. However I tend to agree with your point about streaming classes. In this way all schools woukd have ' grammar ' streams and their would be no flight to areas with good schools. That is assuming the teachers , leadership etc were also equal across the school's. Also teacher might feel differently about schools if they were not expected to differentiate lessons from one extreme to the other. Nobody is satisfied. Indeed some teachers are probably more skilled at teaching some pupils than others and enjoy it.

Very very sadly I have seen children being dragged through a curriculum despite not understanding or following the subject. I cannot imagine what it is like for a child to enter every lesson with a feeling of failure and embarrassment. I have seen children being taught algebra gcse statistics who cannot do H T U addition let alone division. This was in a streamed class for maths and all the parents wanted their child to sit the GCSE, as was their right.

Those pupils were left ill equipped for life.

I really do not wish to get into the personal debate about Julian’s blog. However I do think that, in order to have a debate, someone must present some proposals about which we can then debate.

Peter Norman was the first contributor and it is my view that he correctly identifies that selective education creates more problems than it solves. I have worked as an officer in Kent and Buckinghamshire where there is almost total reliance on the norm referenced 11+. This means that the pass mark can fluctuate each year depending on the number of places available in local grammar schools. In some areas children, well outside the area, take the test as ‘practice’. They are offered places but do not take them up, leaving vacancies in September. The result is that in September some children, who have started at another school having narrowly missed the threshold (which remember fluctuates each year), then go through another selection process in which they may or may not be successful. Others travel considerable distances each day, which means that a grammar school does not necessarily provide for its local community.

I am a governor of a large high performing primary school. In 2016 37 year 6 children attained well above the National average in English, and maths in the key stage 2 assessment and one might have expected them all to attend grammar schools. However only 25 achieved the required score in the 11+ test completed 10 months previously. There is something wrong here and, despite claims to the contrary, coaching to pass the test is a cottage industry and unfortunately it means that some children are unable sustain this level of attainment. Recent research by UCL institute of cognitive neuroscience suggests that 11+ tests are not ‘tutor proof’. They assume a fixed mind set about learning whereas many teachers realise that this is unhelpful and adopt a growth mind set approach to their teaching and learning.

In 2016 I supported a child of Nigerian origin who had ‘failed the 11+’. His parents have high aspirations. One is a hospital porter and the other works in a care home and they desperately wanted their son to follow his two sisters and obtain a grammar school place. He had ‘failed’ the 11+ test. What drove them was that both daughters had also failed the 11+ test and obtained places in year 7 on appeal, and the eldest is now at university. Yes this was social mobility but the daughters were fortunate. The son is attending a local school which, unlike the grammar school, is judged to require improvement. There is so much luck involved in the selection process and this can so easily close down opportunities for a child.

Parents tell me that they want the grammar school because it is “independent education paid for by the state”. They also complain that, having paid out excessive fees in tutoring for the 11+ test, many grammar schools expect them to make a monthly contribution, typically £200. This would be a considerable outlay for the Nigerian family and, in my experience, grammar schools are more about social exclusion than social mobility.

In some towns there is ‘middle class’ flight to the schools on the periphery which leaves the town secondary schools devoid of the most motivated children and parents, and some schools find that recruiting the best teachers can be difficult. This can mean that Ofsted judge all the grammar schools to be good or outstanding because of the headline academic performance, and all the remaining schools, with weaker academic performance, can too easily be judged to ‘require improvement’. The result is that unless a child is successful in the 11+ test then parents have a limited choice of schools. This is a particular issue for children who receive the Pupil Premium who are entitled to attend a ‘good’ secondary school. If they do not pass the 11+, then their choices are limited and parents may have to make complex and expensive travel arrangements and the child does not learn within the local community.

I am happy to debate this issue but please might we look carefully at what the research tells us.

I remember reading that after the grammar schools were abolished, some local authorities still continued with the 11-plus exam, for research purposes. They found that 11-plus results were an extremely poor indicator of those who eventually gained a university place. As I remember, 30-40% of those who failed the 11-plus got to university from their comprehensive school. The age of eleven is far too early to judge children's potential.

Charles, Bryn, Clive and Steven,

I thought it might be helpful if I offered some thoughts about the process (rather than policy) issues you raise.

I fully recognise that the RSA isn’t a political party which whips its members into line behind a collective position. Indeed, debate and respectful disagreement is our life-blood – it’s what draws people to the RSA and what elevates our discussions above the vacuous blandness of so much contemporary political debate. I hadn’t therefore intended to convey the impression that all 28,000 RSA Fellows agreed with the position I set out, and I should have made that clearer in my blog. The good news is that readers of the letter to The Times that I signed would have only seen "Julian Astle, Director of Education, RSA" (my name and job title) among a long list of other signatories. The inference of institutional support for my views was therefore stronger in my blog than it was in the newspaper.

That said, I do see it very much as part of my job to speak out on policy issues of importance to the Society. And when I do so, I will inevitably be seen by some to be speaking on behalf of the institution as a whole, however implausible that may be for an organisation as large and diverse as ours. That is why, when I voice an opinion in the public square, I seek, as far as possible, to construct a rational argument that is based on the evidence and that is consistent with the RSA's values and stated mission.

As to whether my blog meets this last test (values and mission), I would argue that, as the sponsor of seven comprehensive academies that pride themselves on their inclusiveness, the RSA's opposition to selection at age 11 is not only implicit, but widely assumed.

Julian

Oh dear! The best strategy when you find yourself in a hole as deep as this one, Julian, is to stop digging. The claim that you have presented a rational argument based on (some of) the evidence is not disputed, but the evidence was clearly pre-selected to provide a preconceived conclusion. It may, or may not, be consistent with the philosophies of some seven academies, but I am sure that there are seven grammar schools who would dispute your interpretations. The fact that your public entry into this debate was, as you admit, that of the director of education at the Royal Society of Arts, will undoubtedly give the public impression that your personal view, in some way, is also that of the Society's members. However, I would not be surprised if members would like to be involved in a debate before the (alleged) conclusion is announced by a senior member of staff. Even at the risk of appearing "vacuous and bland" by daring a contrary view