Earlier this week The Times newspaper published a letter, signed by representatives of 60 organisations committed to expanding the life chances disadvantaged children, making clear their opposition to the government’s plan to overturn the ban on new grammar schools. I was more than happy to add my name, and that of the RSA, to the letter. This is why.

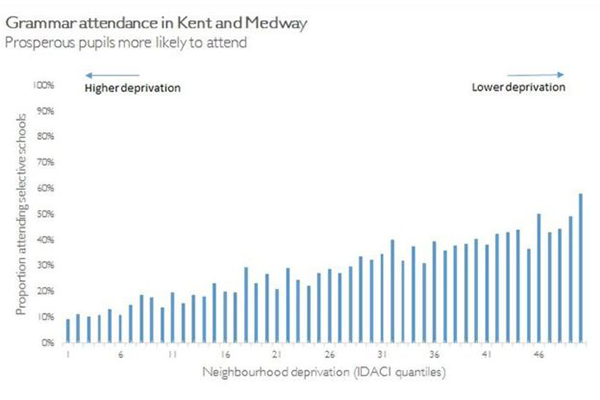

As others have not only claimed but proven, grammar schools simply don’t do what their supporters claim they do – act as an engine of social mobility, allowing bright but poor kids to reach their full potential, boosting England’s educational performance in the process. That is because, as the BBC’s Chris Cook has demonstrated, grammar schools simply don’t teach very many bright but poor kids, having long since been colonised by the sharp-elbowed middle classes. As the table below shows, in Kent and Medway (a selective education authority) a young person living in the poorest neighbourhood in county has a less than 10 per cent chance of attending a grammar school, while someone living in the wealthiest neighbourhood has a more than 50 per cent chance of doing so. Why? Because not only has 60 per cent of the attainment gap between rich and poor pupils already opened up by the age of 11 when the entrance exam is taken (making it far less likely that poor kids will pass it), but the system is further skewed in favour of the rich by the fact that the entrance exam – notionally a test of intelligence rather than knowledge – can be gamed, so long as you can afford the private tuition designed and explicitly marketed for that purpose.

Kent and Medway is much discussed because the county hosts such a large number of grammar schools. But have opponents of selection seized on it because it supports their case in a way that a broader, country-wide analysis might not? No. Across England, 13.2 per cent of secondary school pupils are poor enough to be eligible for free school meals (FSM), compared to just 2.5 per cent of grammar school pupils. This cannot be explained solely by the fact that FSM pupils are, on average, well behind non-FSM pupils by the time the 11+ exam has to be sat. As the Education Policy Institute has shown, 6 per cent of high attaining pupils at the end of primary school (the highest attaining 25 per cent) are eligible for free school meals, yet the number of FSM pupils in selective schools is less than half this – a gap that gives some indication of the size of the ‘tutor effect’, among other factors. Nor can the social exclusivity of grammar schools be explained away by some quirk of geography – the possibility, however remote, that bright but poor pupils live too far away from these schools to attend them. Pupils eligible for free school meals make up 6.9 per cent of the high-attaining group living within travelling distance of a selective school – higher than the proportion of high attaining kids who are eligible for free meals across the country as a whole. As wealthier children travel significant distances (twice as far on average) to attend grammars, bright but poor local children remain shut out.

The tragedy, for all those highly able but poor pupils living near to a grammar that they do not attend, is that the very existence of a selective school in an area does real damage to the educational prospects of students in non-selective schools nearby. In non-selective local authority areas 57 per cent of pupils achieve five A*-C GCSEs including English and maths. In selective authorities that figure drops to 47 per cent. The impact on FSM pupils of going to a non-selective school in a selective area (a de facto ‘secondary modern’) compared to a non-selective school in a non-selective area (a comprehensive school) is also stark. In the former, only 27 per cent of FSM pupils get their five good GCSEs including English and maths, compared to 35 per cent in the latter.

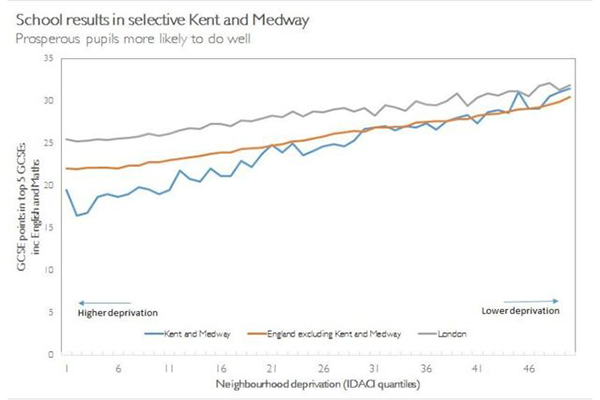

The consequence, unsurprisingly, is greater inequality, with grammar schools almost guaranteeing high attainment for the relatively wealthy minority who attend them (97 per cent of grammar school pupils achieve 5 A*-C GCSEs including English and maths), while damaging the performance of the poorer majority who do not. If we return to Kent and Medway, we can see that all but the very least deprived pupils do worse than elsewhere in England, resulting in a lower aggregate performance for the county as a whole.

But the most interesting comparison – and the one that most frustrates those who have been working so hard over recent years to drive up the quality of comprehensive education – is with London, where performance in non-selective schools has rocketed to such a degree that people are now flying in to the capital from around the world to find out how it was achieved.

The fact that the grey line never drops below the blue line, and that it rises more gently, tells us that it is possible to build a non-selective education system that raises standards for all; a more equal system which benefits the poor while doing no worse for the rich.

Which brings us back to the Educational Policy Institute’s key finding: that in terms of the progress that pupils make while at school, high quality non-selective schools (the top 25 per cent by value added) are outperforming grammar schools, doing so at scale (there are five times more high quality non-selective schools as there are grammars) and doing it for everyone (12.6 per cent of their pupils are eligible for free school meals versus 13.2 per cent nationally and 2.5 per cent in grammars).

Little surprise then that researchers at the London School of Economics found that the early academy schools that powered so much of the increase in London’s educational outcomes over the last decade and a half, are the real engines of social mobility, educating 50,000 FSM-eligible pupils compared to the 4,000 in grammars, adding real value (a full grade per pupil across five GCSEs) and transforming life chances (increasing the number of pupils going on to university by a third).

Anyway, enough numbers.

The real point here is not that grammar schools aren’t good schools. Or indeed that we should disapprove of a parent’s decision to send their children to a grammar school. On the contrary, a parent’s first responsibility is to do the best they can by their own children and a grammar education is as close to a guarantee of success as can be found in the state sector.

Rather, it is that this is a classic case of the private and public interest colliding. From a system perspective (which is, of course, the Prime Minister’s first responsibility), the evidence is clear: grammar schools do more harm than good. Researchers have found no evidence of any positive impact on attainment by grammars that isn’t explained by the relative wealth and high prior attainment of their pupils. But they have found plenty of evidence of them doing very real damage to the performance and prospects of non-grammar school pupils in the area where they are located. That’s a lot of losers for a small number of winners whose needs would be met just as well by the best comprehensive schools.

That is why the coalition of organisations to which I added the RSA’s name is so wide – spanning the political spectrum and encompassing academics and teachers, charities and professional bodies. There is much about education policy that will continue to divide us. But on the importance of not returning to a system that pushes children down two different life-altering paths at the age of 11, we all agree: that is not how you build “a country that works for everyone”.

Related articles

-

What role can schools play in developing young people’s social agency?

Hannah Breeze

"Social action as a means of developing and expressing character might just be the antidote to the ‘education by numbers’ system", argues Hannah Breeze from the RSA Academies team.

-

Education versus poverty

Julian Astle

Do we distribute the education budget in a way that is likely to help children overcome the many barriers poverty places in their way?

-

Student voice: how New York schools are tackling social injustice

Naomi Bath

Naomi Bath reflects on a recent trip to New York visiting schools, sketching out different ways in which students are using their voice to tackle social injustice.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

Is it right for you to assume that you speak for the Fellowship - and, therefore, for me as a Fellow - in this way? I have no objection to people - either Fellows or staff members - holding personal views and debating them within the RSA, but to assume that one's position will inevitably be that of the RSA and its Fellowship without first asking us is a little presumptuous. I don't necessarily disagree with the views you have outlined - I sat the 11-Plus myself and failed it but then had a second chance because my family moved to another county which had a Comprehensive system in place; I am certainly not, therefore, a product of the Grammar School system nor an advocate for a return to that system. I am not in favour of selection at 11 - but nor, as I understand it, are many of those who are supportive of the Grammar School idea. Let's by all means have a debate on this, but let's also avoid staff members of the RSA publicly endorsing a position on behalf of the RSA, through the assumption that their position will automatically reflect that of the Fellowship.

I don't much care for the fanatical pro and fanatical anti parties in this debate. If we have "had enough of experts", why can't we let local people decide? Isn't this what democracy is all about?

Great article, Julian - thank you. I have been a headteacher in both a comprehensive school in non-selective Oxfordshire and a secondary modern in selective Buckinghamshire (my current post) and have experienced the issues you write so lucidly about at first hand in the lives of the young people in both schools and the broader populations of the local communities. My contribution to this discussion is to suggest that selective schooling creates a 'pecking order' of schools in the towns, which is energised by the local media and drives social attitudes, relationships, employment prospects, house prices and more across the town, embedding deep-level segregation across a whole community that is not restricted to school-age young people. In this way the negative effects of selection become an accepted part of the status quo, 'the way things are'. Having tried to shift attitudes I am only too aware of just how difficult it is to challenge successfully people's prejudices and assumptions in this area. It's great to have the 'clout' of the RSA arguing for enlightened attitudes.