£133bn was spent online with UK retailers in 2016, up £18bn from 2015. Meanwhile, the high street stalwart BHS closed its doors for the last time. Physical retail is in decline. While e-commerce is on the rise. What does this mean for the health of our economy and the vibrancy of high streets across the country?

The shift from shops to servers

E-commerce is changing the labour needs of retail. Order something online and you will promptly receive an email along the lines of “we just wanted to let you know that your order has been packed at our warehouse and will be picked up by a courier shortly”.

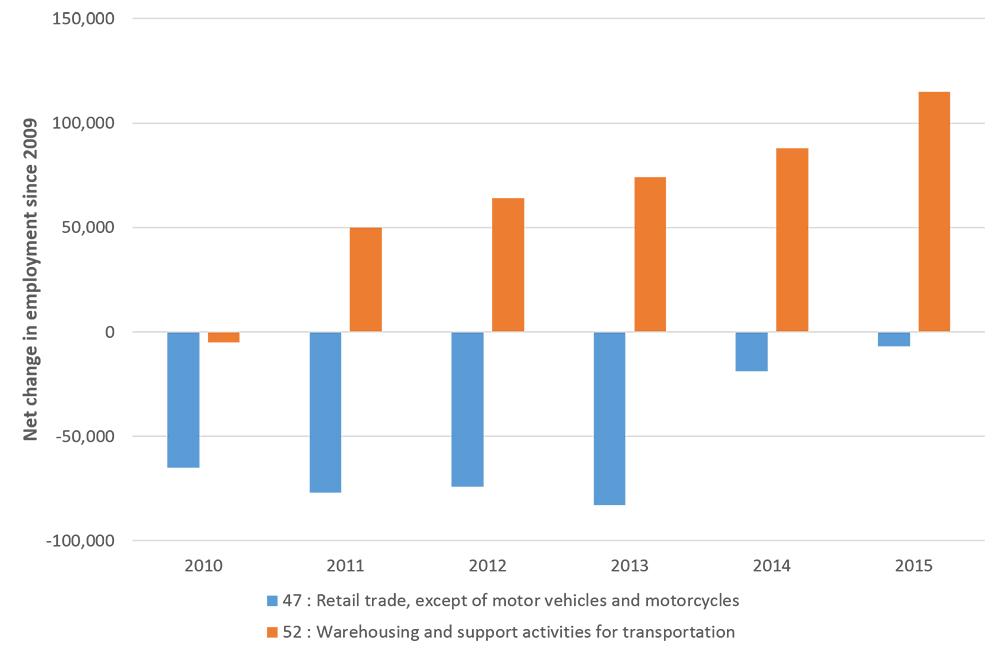

An analysis by the economist Michael Mandel of US retail jobs growth provides further evidence of this shift. Since 2007, the decline in US retail jobs was offset by an increase in the number of people working in warehousing. When we consider these two industries in tandem, there are signs that a similar trend has played out in the UK. RSA analysis of BRES suggests that any decline in retail since 2009 was more than soaked up by an increase in warehousing.

Figure 1: Net changes in retail and warehousing employment since 2009. Source: RSA analysis of The Business Register and Employment Survey (BRES)

Retail seems to have finally recovered from its post-2008 slump but is yet to see positive jobs growth. Meanwhile warehousing has gone from strength to strength.

What’s more, these jobs are much better paid

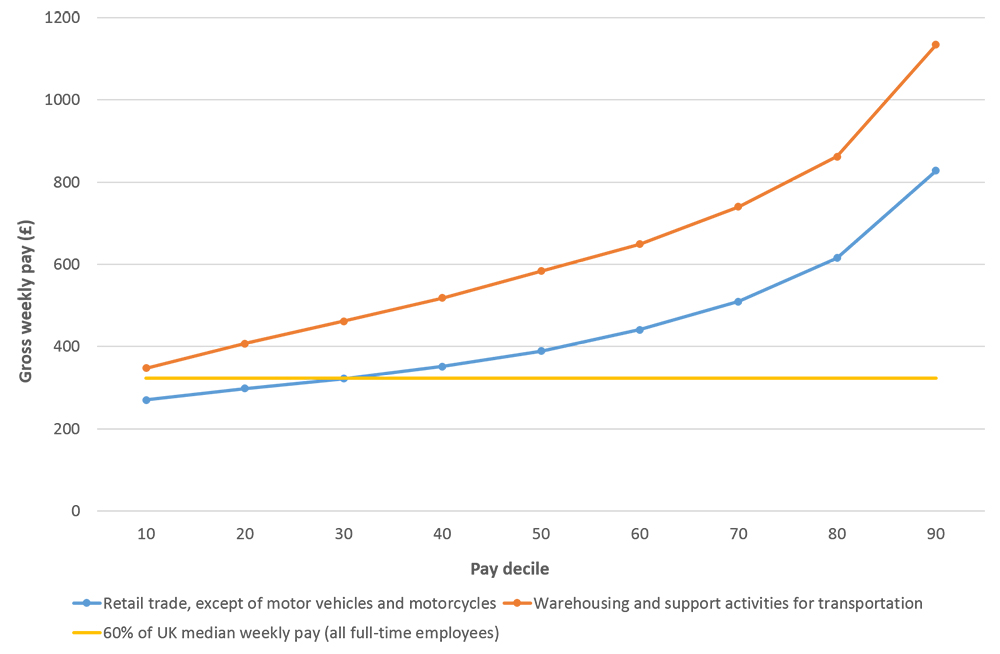

The typical (median) weekly wage for a full-time warehouse employee is £583, compared to just £389 for a retail employee. Across the income distribution, warehousing jobs are much more generous. At least 30% of full-time retail employees fall below the low pay threshold (60% of the median wage). While less than 10% of warehousing employees fall below this threshold.

Figure 2: Gross weekly pay deciles for full-time employees in retail and warehousing. Source: RSA analysis of Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE), 2016

So there is at least one upside to this trend. Jobs in warehousing are more likely to provide workers with economic security. What explains this wage difference? Retailers' profit margins may be tighter because of the extra costs associated with high street rents, business rates and maintaining the shop floor.

But who could lose out?

When judging whether or not technological change (much like public policy) is good or bad, we need look at not only whether or not there are net benefits but how these are distributed.

In this particular instance, we need to pay close attention to:

- Gender inequalities in job loss and creation

- Market concentration and how this impacts local economies

- Social isolation and the non-economic value of the high street

- Geographical disparities in job loss and creation

Automation has a significant gender dimension here. 57% of retail workers are women compared to just 31% of warehouse workers. Although the force of these concerns may depend on whether we take a long-run view. For many of the jobs which are considered to be more resilient to automation, such as teachers and care workers, have a much larger share of female employees. PwC estimate that 26% of women’s jobs could be replaced by robots, compared to 35% of men.

Amazon accounted for 43% of US online retail sales in 2016 and is the market leader in the UK. Will the shift to servers result in less money circulating around local economies, if e-commerce is ruled by behemoths? The picture here is complex. RSA analysis of The Business Population Estimates (BPE) indicates that small and medium enterprises actually account for a larger share of total turnover in warehousing than in retail (47% v 28%). Not everything sold online is fulfilled by Amazon, while much of what we spend on the high street also lines the pockets of larger businesses.

However, we need to also pay attention to the non-economic value of our high streets. According to the Opinions and Lifestyle Survey, 1 in 7 working age adults report high levels of loneliness. For elderly people aged 80 and older, this figure is closer to 30%. High streets can play an important role here. A trip down the shops may be their only social interaction this week.

Perhaps retail will never completely lose its ‘in-store’, experiential element, as surveys indicate that many consumers continue to feel the need to touch and feel products before they purchase. Indeed future of retail evangelists purport that new technologies such as augmented reality will enhance this experience. We can imagine this in flagship stores on Oxford Street. But will we see it in Oldham?

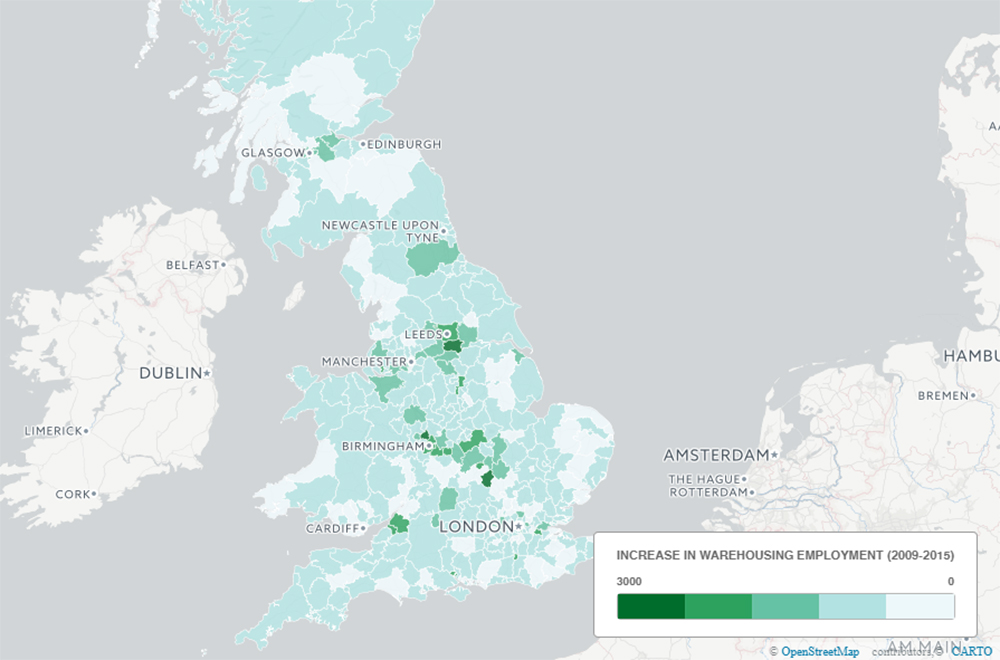

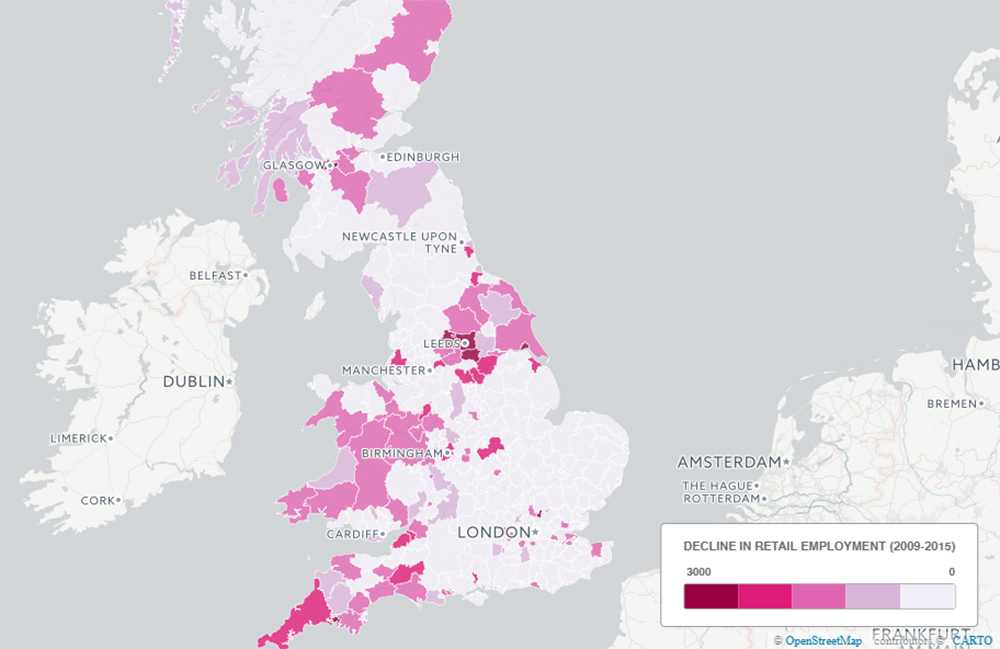

Geographical disparities are particularly concerning. RSA analysis of BRES shows that the major gains in warehousing employment are more spatially concentrated than the losses in retail. So, at a local authority level, there are more significant losers from this trend.

Figure 3: Disparities in warehousing growth and retail decline across Britain. Source: RSA analysis of BRES

What do these maps illustrate? Most local authority districts experienced a small increase in warehousing jobs but only 49 experienced an increase equal to or greater than 1,000. Meanwhile 73 areas experienced a decline in retail employment equal to or greater than 1,000. In areas such as Leeds, retail jobs seem to have been substituted with warehousing jobs but the same cannot be said for swathes of Wales and the South West. Meanwhile places such as Milton Keynes have gained 6,000 new warehousing jobs.

Towards a more intelligent analysis

Our recent report on AI, robotics and the future of low skilled work, explores how these technologies have the potential to exacerbate these trends. AI will make online retail more attractive and enjoyable. Robotics will make warehousing more efficient but also place some of these new jobs at greater risk of automation.

The shift from shops to servers provides a case study, both for researchers to think more widely about how we predict and evaluate the impacts of new technology, and for policy makers who need to prepare for these impacts. It demonstrates the need to get beyond headlines about the number of jobs that will be automated. There will be winners and losers. We need more intelligent analyses that explore how new technologies will impact local economies so that policy makers can steer support where it is needed.

Read our report online: The Age of Automation (on Medium)

Download the report: The Age of Automation (PDF, 1MB)

Related articles

-

8 ideas for a new social contract for good work

Alan Lockey Fabian Wallace-Stephens

Alongside the moral urgency of the pandemic, the challenges of growing economic insecurity and labour market transforming technologies require a new social contract for work.

-

Low pay, lack of homeworking: why workers are suffering during lockdown

Fabian Wallace-Stephens Will Grimond

New RSA analysis finds that those least able to work from home are often the lowest paid.

-

Four futures of skills and learning in Scotland

Fabian Wallace-Stephens

What skills will workers need in the future? And how should educators, employers and policy makers respond to shifts in the labour market? We worked with Skills Development Scotland to explore these questions.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.